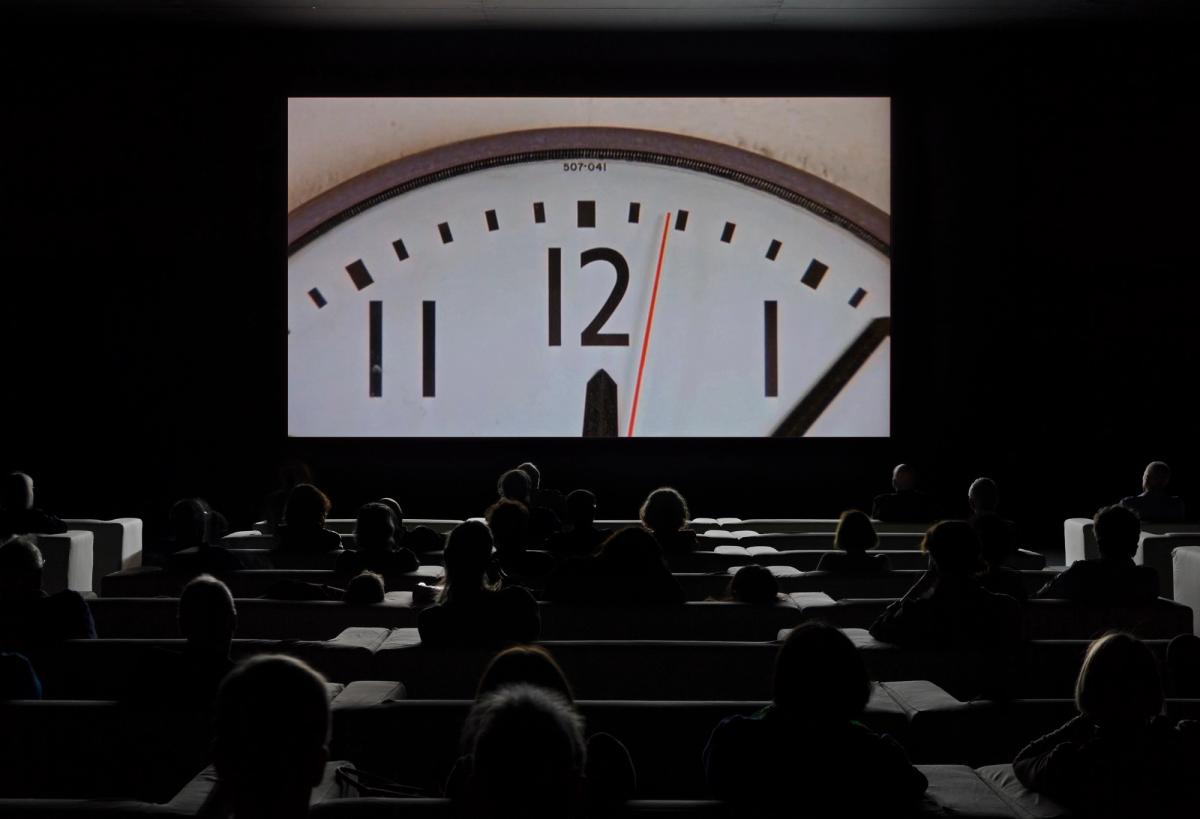

Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010), which opened at Tate Modern earlier this week, has been hailed as one of the first masterpieces of the 21st century.

The 24-hour film, a moving-image collage made from excerpts of thousands of films that feature timepieces from clocktowers to pocket watches, is synchronised so that it actually tells the time. It also links clips from disparate movies from 100 years of cinema in inspired, spellbinding ways. It is a miraculous feat of editing. And it has enthralled audiences around the world.

But in this week’s The Art Newspaper podcast, Marclay tells us about the demands made on him as he edited the film over three years. Asked if it played tricks on his mind, he replies: “It was more physical, being in the same position, editing, sitting down in front of the computer. I had some problems with my hand after a certain point, callouses. I had to start yoga after a certain point, to relieve the tension—which was a good thing, because I still do it. Physically, it was tough. Now it’s been ten or 11 years since I started that project, I find sitting in front of a computer all day editing more and more difficult.”

The film has returned to London for the first time since it premiered at White Cube in Mason’s Yard in 2010—it was jointly acquired by the Tate with the Centre Pompidou, Paris and the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, in 2012. Since its first showing, it has drawn crowds in museums as far and wide as Sydney, Yokohama, Istanbul, Moscow, Montréal and Los Angeles. It has also been acquired by Los Angeles County Museum of Art, jointly by the National Gallery of Canada and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and again jointly by the Kunsthaus Zurich and the Luma Foundation in Arles. It is a promised gift to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a private US collector has the only edition not in a museum.

On its return to the city in which it was made, Marclay says: “It’s exciting, especially in this new building and in the fact that it’s free and people can come back as many times as they want to, if they’re lucky enough that there isn’t too much of a queue.”

The film is a meditation on time in numerous ways, among them that it suspends now long-dead actors in a precise moment, forever, and that it marks the changing nature of places, of fashions, architecture and design. But it also obliquely captures the moment and the place when and where The Clock was made. “It’s very much a portrait of all the video rental shops that have disappeared in the last 10 years,” Marclay says. “Everybody downloads their films [now]. It’s very much about what was available in London during those three years that I was making The Clock. And a lot of British movies were featured because they were available. And, of course, if the action happens in London, you’re pretty sure there’s going to be a Big Ben shot.”

You can hear the full interview on The Art Newspaper Podcast and all the usual places where you find podcasts including iTunes, Soundcloud and TuneIn. This podcast is brought to you in association with Bonhams, auctioneers since 1793. Find what defines you. bonhams.com/define