The Baltimore Museum of Art, founded in 1914, is extending its modern art chronology with a new wing for post-war art, which opened in mid-October. The three-storey aluminium-clad addition adjoins the early-modern galleries of the existing Beaux-Arts building, linked by means of a public rotunda which has an oculus high above Henry Moore’s marble “Three Rings” (1966).

Several portals lead to light-grey galleries with white ash flooring and twenty-five foot ceilings, bathed in cost-reducing cool fluorescent light. The rooms are laid out in twenty-five foot squares, some single, some double, and the central gallery a quadruple 50 x 50 x 50-foot cube.

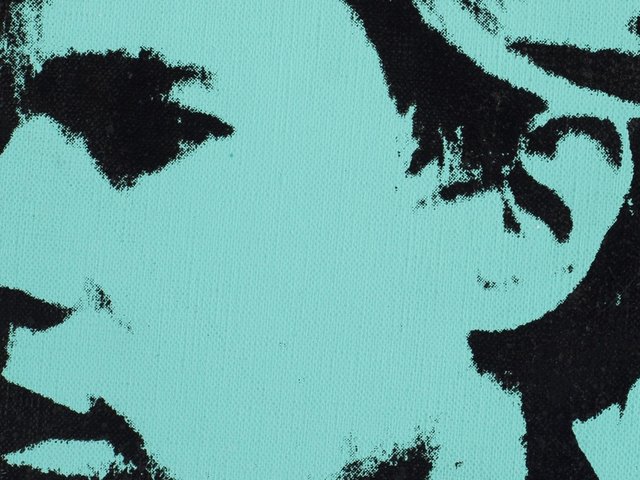

This pivotal chamber, the heart of the new building, will be devoted to thirty-odd works by Andy Warhol. Brenda Richardson, the museum’s deputy director for art and curator for Modern Painting and Sculpture, defends the centrality of Warhol in her scheme, declaring “I have no doubt whatsoever about the role that he will have in the history of art”. Even if her predictions were true, however, it may seem somewhat odd that the museum has acquired and exhibited dozens of Warhols, but nothing by any of his Pop contemporaries. Indeed, the decision to give Warhol pride of place looks like it had more to do with projected attendance than with art history or aesthetics – especially coming as it does in the immediate aftermath of the heavily hyped opening of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, and amid the torrent of press surrounding the Warhol Estate trial.

Baltimore’s career-spanning Warholian wonderland was cobbled together with loans of fourteen pre-1965 works from the artist’s one-time dealer Ileana Sonnabend, and with eighteen post-1975 works purchased in May from the Warhol Foundation for “half their appraised value” (a matter still open to debate). Faced with this “extraordinary opportunity”, rather than acquire a single expensive early work, Baltimore opted for a spate of late ones (fifteen paintings and three drawings), among which are the 13 x 10 -foot “Rorschach” (1984) and the 10 x 35-foot “Hearts” (1979).

Surrounding galleries display the balance of Baltimore’s post-war art, almost exclusively American painting and sculpture, with particular emphasis on geometric abstraction and minimalism of the late 1960s and early 1970s (Stella, Judd, Kelly, Johns, Serra, etc.), and a sampling from the preceding generation (Gorky, Kline, David Smith, Still).

Missing are major pictures by Pollock, Newman, Ryman, Twombly, Agnes Martin, early Brice Marden, late de Kooning, and as noted, the Pop artists other than Warhol. Ms Richardson’s hang has been governed more by “the harmonic interplay between objects” than by chronology, medium or content. Nonetheless, the installation keeps each artist’s works in relative proximity to one another and to their contemporaries.

The upper floor is reserved for Post-Modernism since the late 1980s, mainly photo-based and socio-political works (Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Meyer Vaisman, Robert Colescott, Cady Noland, etc).

The museum built a treasure for the purchase of post-war art when it auctioned off 104 works from the permanent collection in the mid-1980s. “We sold at the height of the market, and spent during the downturn, and we were able to negotiate very good prices”, says Ms Richardson.

The 36,000-square foot addition is the latest in a series of capital projects that have modernised and expanded the museum, added outdoor sculpture gardens, and created an auditorium, cafe and shop, all with the collaboration of the Philadelphia architectural firm of Bower Lewis Thrower. More than half of the wing’s $10-million price tag was donated by the State of Maryland and the City of Baltimore; another $3.9 million came from private donors, trustees and local corporations; and the Kresge Foundation gave $600,000. Individual galleries have been named after donors whose names appear on the door jambs, but the building itself remains “a naming opportunity”, generically referred to as “the new wing for modern art”, even if in spirit it has already become the new Warhol wing.

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'Belgian Expressionists, Warhol and a new museum in Kaohsiung'