A New York appeals court unanimously dismissed the financier Ronald Perelman’s fraud claim against the dealer Larry Gagosian last month, ending a two-year legal battle between the former friends. The case offered a rare peek into back-room negotiations over blue-chip art, but the outcome is as applicable to the flea market as it is to the art market: buyers ought to beware. An art dealer cannot be sued over a statement he or she makes about the value of a work of art, the court concluded, regardless of whether the figure is accurate or not. A statement of value—even from a trusted expert or adviser—is an opinion, not a fact.

No legal obligation to buyer

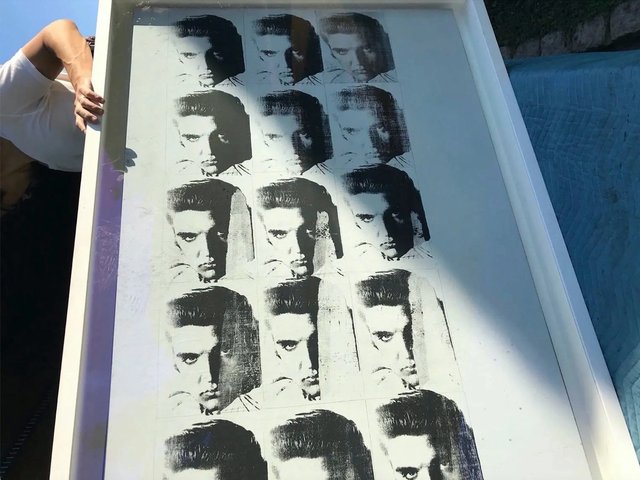

Perelman, the founder of the diversified holding company MacAndrews & Forbes and one of the richest men in the US with an estimated net worth of $14.5bn according to Forbes, sought to prove that Gagosian had concealed vital information and unfairly manipulated prices in a series of deals involving around $23m worth of art. The financier claimed that Gagosian had a fiduciary duty (a legal obligation to act solely in another party’s interest) to Perelman, his friend, business associate and client of more than 20 years. Perelman trusted Gagosian because of their long history and the dealer’s “unparalleled knowledge and dominant position in the art world”, according to the initial lawsuit, which was filed in September 2012.

A five-judge panel maintained on 4 December that Gagosian has no fiduciary duty to Perelman, a sophisticated art market player in his own right. Perelman has a dedicated art fund and his collection is worth around $1bn, according to the New York Times. “The complaint does not establish that defendants exercised control and dominance over plaintiffs—limited liability companies who, by their own description, frequently purchased, sold and exchanged works of art as investments,” the court said.

As well as dismissing the fraud claim, the panel re-enforced a decision made by a lower court in January 2014 to dismiss five of the six claims Perelman brought against Gagosian, including deceptive business practices and breach of fiduciary duty.

“Show us your market data”

Crucially, the court went on to say that it was Perelman’s responsibility to confirm whether the prices Gagosian quoted—including $4m for the sculpture Popeye, 2009-11, by Jeff Koons, and $10.5m for the painting Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves, 2009, by Cy Twombly—were fair. “These sophisticated plaintiffs cannot demonstrate reasonable reliance because they conducted no due diligence; for example, they did not ask defendants, ‘Show us your market data’,” the court said. Gagosian’s statements about the value of works of art constituted “non-actionable opinion”, according to the judges, and therefore they “provide no basis for a fraud claim”.

There is precedent for this conclusion. In 2011, a New York court dismissed Oleksandr Savchuk’s fraud claim against the ABA Gallery, in which the collector accused the New York gallery of duping him into buying 18 paintings for an inflated price of $9.6m. “There is no objective, discernible fair market value except perhaps for fungible assets traded on an efficient market,” the judge concluded. In fact, the only definition of “fair market value” for a work of art is “the price that a willing buyer and a willing seller would agree to in an arm’s length transaction”, he wrote.

Opinions don’t count

An appeals court came to the same conclusion in a 2011 dispute between the dealer Guy Wildenstein and the company Mandarin Trading. The court ruled that Wildenstein did not commit fraud when he gave his opinion that a painting by Paul Gauguin that Mandarin owned was worth between $15m to $17m, despite the fact that it later failed to sell at auction.

Last month’s decision, issued during Art Basel in Miami Beach, probably came as a relief not only to Gagosian but also the many art-world figures and businesses that Perelman had subpoenaed during the proceedings, including the investor-collectors Alberto, Jose and David Mugrabi, the auction houses Sotheby’s and Phillips, the artist Jeff Koons and Sonnabend Gallery.

MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings and Perelman’s lawyer declined to comment on the outcome and whether they planned to appeal. A spokesperson for Perelman’s company told Bloomberg: “When it comes to the art market apparently it’s buyer beware and when it comes to Larry Gagosian it’s buyer be damned.”

Gagosian’s lawyer, Matthew Dontzin of Dontzin, Nagy & Fleissig, said in a statement that the ruling reinforced “our view that in keeping with Perelman’s lengthy history of unsuccessfully trying to use the courts to bully his business associates, this lawsuit was filed as a shameless pretext for Perelman’s refusal to pay what he owed the gallery”.