The Syrian photographer, gallerist and curator Issa Touma is determined to return to Aleppo. Speaking from the Netherlands last month, he says that he will return to the besieged city through the desert to continue the Art Camping project. Anywhere from five to around 50 people—depending on the security of the areas they come from—meet in his gallery to express themselves through art, despite the war raging around them. He is also hoping to restage the Aleppo International Photography Festival this year. With four other Syrian artists who have also decided to stay in the city, Touma took part in Postcard from Syria: Art is Peace, an exhibition that went on show in Singapore’s Sana Gallery last November. In Paris the same month, he presented a book of portraits of 15 young women who took refuge in his gallery, having fled Islamic extremists. Touma spoke to our sister paper, Le Journal des Arts, as he planned to head back to Aleppo and Le Pont, the gallery he founded in 1996.

It’s the first time that works by these artists living in Aleppo have been shown; why choose Singapore?

It was at the initiative of the Sana Gallery, the first gallery dedicated to Middle Eastern art in Singapore, that we chose to present this exhibition. It took over a month to transport the works, which were able to go from Aleppo to Beirut [in early September]. We were really lucky since the route was quickly blocked by Isil. The works then continued their journey to Singapore by plane.

What is everyday life like in Aleppo today?

In 2013, there were 2.7 million inhabitants in Aleppo; today, there are barely one million. Living in Aleppo means living without water, without electricity, without internet. We went 245 days without internet communication. All the artists [in Postcard from Syria] have their studios a few hundred metres from the front. When I visited my friend Hagop Jamkochian a few months ago, he had painted a considerable number of canvases in five years. He told me: “I hear the music”, but this music is in fact the noise of bombs. The war is unfolding 300m from his home. As for [the artist] Thaer [Hizzi], he lost his studio in the bombings. He lost everything. He only had a few A4 sheets on which he continued to draw. We all know that we could die at any second, but we must stay, we must show the soldiers that we are going to continue to live, otherwise they’re the ones who will win.

How have you managed to maintain an artistic life in Aleppo in this context of war?

When the first refugees began to arrive in Aleppo in 2012, I created Art Camping in my gallery. The idea was to enable the residents of Aleppo and the refugees to exchange views through art. Here, Christians, Muslims, pro- and anti-government don’t fight one another; on the contrary, they work together. Everyone can participate, there’s no need to be an artist. Art brings us together and gives us hope that we can push back against the war. Art helps us to smile, to survive, it’s what allows us to protect ourselves mentally and remain human. Through Art Camping and thanks to art, I wanted to give a voice to all those people who are dying in silence. We brought together as many as 500 members two years ago.

What types of project have you carried out and are you working on at Art Camping?

We have developed many projects like a video on daily life in Aleppo in 2013, when the city turned violent after the arrival of the rebels. We have also painted smileys on satellite antennae and even organised a street carnival. In 2012, we also went into an historic neighbourhood of the city, paper and charcoal in hand, in order to take “imprints” of textures and emblematic motifs of the city; one year later the neighbourhood was destroyed. The more they sow war, the more we fight with art and culture. But that’s not all, since 1997, I have organised [an international] photography festival. I am preparing the 2016 edition, but with the war it’s difficult to settle on a date. It’s a special festival: we are asking artists to send us their photographs, but not to physically attend—it’s too dangerous. By betting on art at all costs, we are on the side of civilisation and showing that the war will not emerge victorious.

Do you sometimes want to leave Aleppo forever?

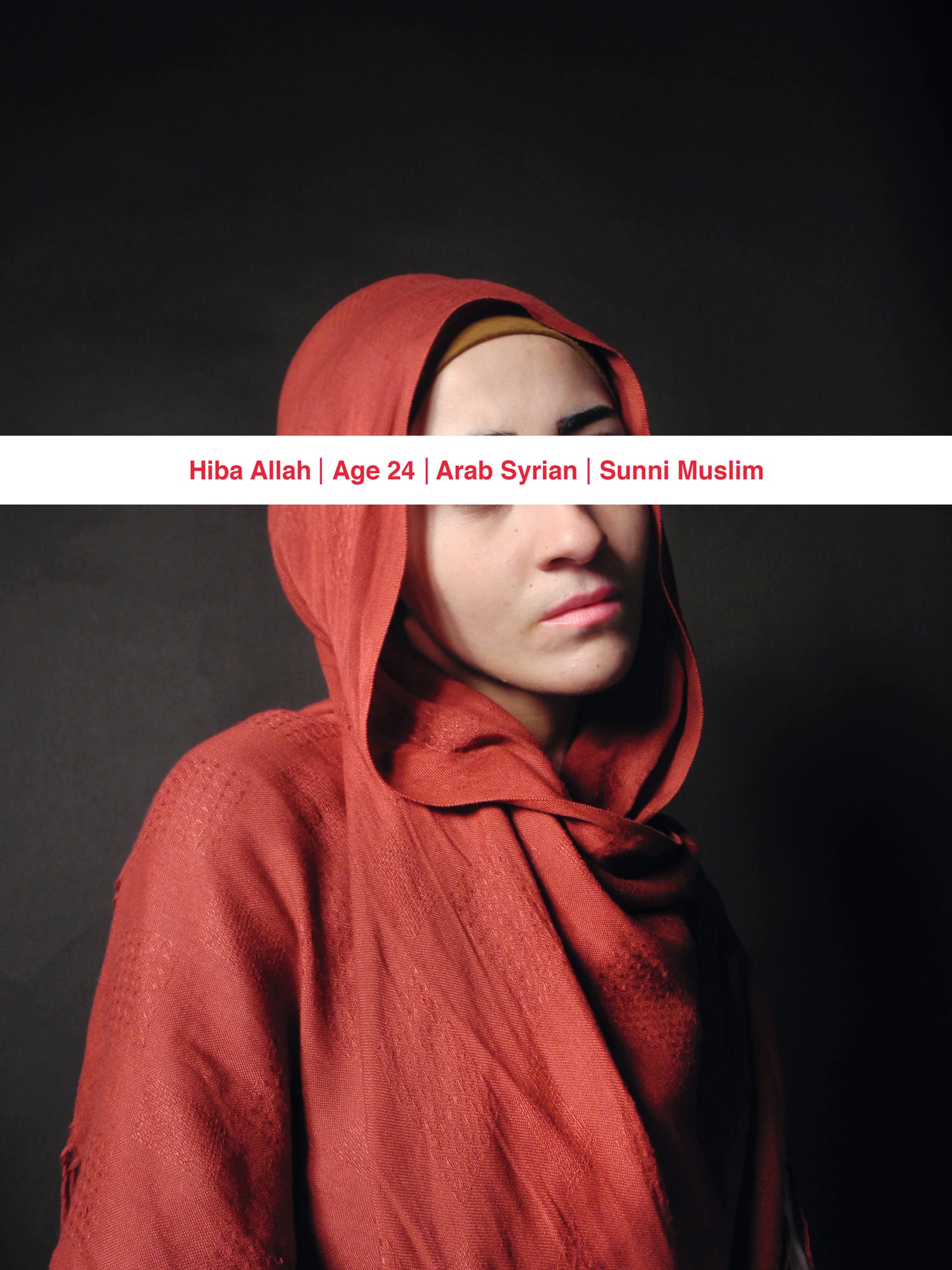

Between 2011 and 2014, I did not leave Aleppo. I wanted to stay and keep up the cultural life. Many intellectuals left the country and, in the end, their discourse was no longer in tune with the reality on the ground. In 2014, I finally felt ready and qualified to speak about my country abroad. I went to Finland, to the Netherlands, to Austria, where I gave conferences on art in war zones, the art of photography in Syria. I also presented my photography exhibition and book Women We Have Not Lost Yet. In April 2015, when the Islamists announced their “major attack” on Aleppo, many women came to seek refuge in my gallery. So we began a photography project. These women are alive, but many of them have been victims of these fanatics. These encounters have resulted in an exhibition and a book. After Paris and Singapore, I am happy to return home, to return to live with my people.

You were at the Paris Photo fair in November during the terrorist attacks in the French capital. Living in a city that has been at war for almost four years, how did you react?

We had a meeting on Saturday, 14 November [the day after the attacks] with several of the photography festival’s team in a café that was only a few metres away from the Bataclan. Many were nervous, but in the end our meeting took place. I am not afraid, I am no longer afraid. It’s sad to say, but I have experience of living in wartime. We have learned how to live in a war zone, we have learned how to move around to avoid bombs.

• Women We Have Not Lost Yet by Issa Touma is published by Paradox and André Frère Éditions