“I began to draw, for bread and cheese, about 1827,” Edward Lear wrote as an old man. In 1827 he was 15 years old, the 20th of 21 children of a soon to be bankrupt London stockbroker and his understandably exhausted wife. Rejected by his mother, and raised as an only child by his eldest sister, Lear was denied (or, if you like, spared) a traditional education, and had to rely on natural ability to make a living. A precocious draughtsman, he got piece-work where he could, including what he called “morbid disease drawings for hospitals”. He had a gift for accuracy that, before photography, could be relied on in scientific contexts to convey precise visual information.

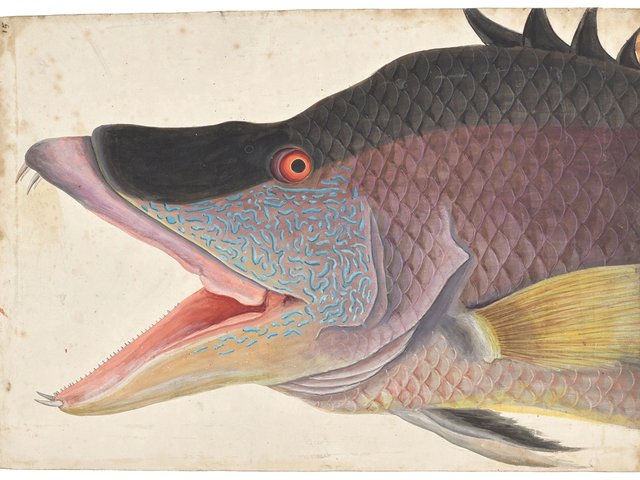

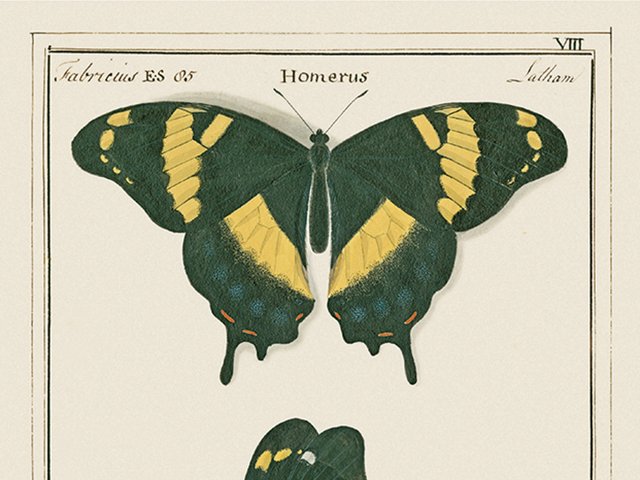

Through medical and scientific patrons Lear became acquainted with the circle of London naturalists gathering, at the start of the 1830s, around the recently founded Zoological Gardens (1825). By the age of 18 Lear had mastered the new technique of lithography and already embarked on his book Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1830-32), now recognised as one of the supreme masterpieces of ornithological art.

Unusually for the time, Lear made his drawings from live specimens. This meant hours spent in the zoo’s aviary, as well as a studio so full of parrot sketches there was nowhere for guests to sit. “For the last 12 months I have so moved—thought—looked at—existed among Parrots,” he wrote to a friend, “that should any transmigration take place at my decease I am sure my soul would be very uncomfortable in anything but one of the Psittacidae.” It was as if Lear found, among these sociable, intelligent, vocal birds, the extended family (that word is conspicuous in the title) that he otherwise lacked. While he never drew human beings with the same success as animals, his animals often have something curiously human about them, a depth of personality, melancholy, or wit.

Other ground-breaking works followed, including not always wholly amicable collaborations with the naturalist John Gould, and 17 of the plates in the belatedly published Gleanings from the Menagerie and Aviary at Knowsley Hall (1846), a description of Lord Derby’s private zoo, then reputed to be the largest in Europe.

By the late 1830s, Lear was itching for a new direction and, using the influential contacts he had made at Knowsley, he went in 1837 to Rome where he reinvented himself as a landscape painter. He lived outside of England for most of the rest of his life and travelled extensively around the Mediterranean, eventually settling in San Remo where he died in 1888. The move to Italy was partly for reasons of health and climate, but Lear’s complex motivations surely included a desire for liberation from the financial, domestic and personal patterns into which his life in England had settled. The decade from 1827 to 1837 was, as Robert Peck writes in The Natural History of Edward Lear, “one of relative stability, working on the details of feathers, fur, and vertebrate anatomy,” but it was also in certain ways one of stagnation for a man still only in his mid-20s.

One of the delights of Peck’s authoritative and sharp-eyed study is that, while it fleshes out Lear’s early career in unprecedented detail, it also demonstrates how much natural history Lear carried with him into his later work both as a landscape painter and as a writer of nonsense. The Natural History of Edward Lear will immediately become the standard work on Lear’s relationships with Gould, William Jardine, Prideaux John Selby and others, on his role documenting voyages of British colonial exploration, and on his technique and craft as an illustrator and lithographer. But it is also full of aperçus about the animals in his landscapes, about his less familiar botanical drawings, and about the overlap between Lear’s scientific work and his poetry.

As Peck persuasively shows, Lear’s career is marked throughout by a sense of his position as an outsider, and this perspective (combined with the impulse to subvert and satirise the orderly, taxonomical discipline of natural history) creates the conditions for his brilliant nonsensical flights. There is, if you are inclined to see it, a double meaning in Peck’s title, both an account of Lear’s natural history and a history of Lear that is natural, framed by and narrated through that fascination with nature which outlived his brief, stellar career as a zoological artist.

This brilliant study convinces us that this is merely the natural way to approach a man who once told a friend, “verily I am an odd bird”.

• James Williams is a lecturer in 19th-century literature and culture at the University of York. He is the co-editor, with Matthew Bevis, of Edward Lear and the Play of Poetry (2016)

The Natural History of Edward Lear

Robert McCracken Peck

David R. Godine in association with the Antique Collectors’ Club, 224pp, £27.99, $40 (hb)