Although little known outside the Netherlands, Johan van Gogh led an extraordinary life. The grandson of Vincent’s brother Theo (1857-91), he represented a link between the artist’s time and our own. Johan suffered two major tragedies in his life: a brother was murdered by the Gestapo and a son by an Islamic extremist.

Obituaries normally deal with the deceased’s working life, but in Johan’s case it still remains shrouded in secrecy, since he served in the Dutch intelligence service. Above all, he should be remembered for supporting his father in handing over the family art collection to the state, which led to the creation of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Along with the Rijksmuseum, it is now the most visited museum in the Netherlands.

Johan died on 21 February, just short of his 97th birthday. Born in 1922, he was one of four children of Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890-1978), the artist’s nephew, who was known as “the Engineer”, after his profession (to distinguish him from his famous relative). The Engineer’s family was brought up with Van Gogh’s paintings lining the walls of their home, including the Sunflowers, which was above a sofa.

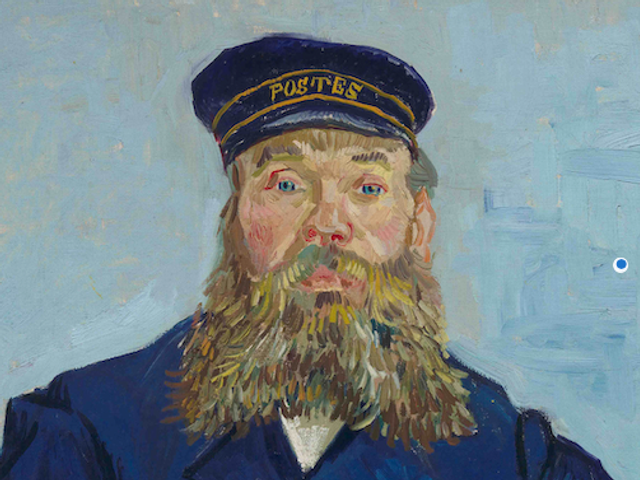

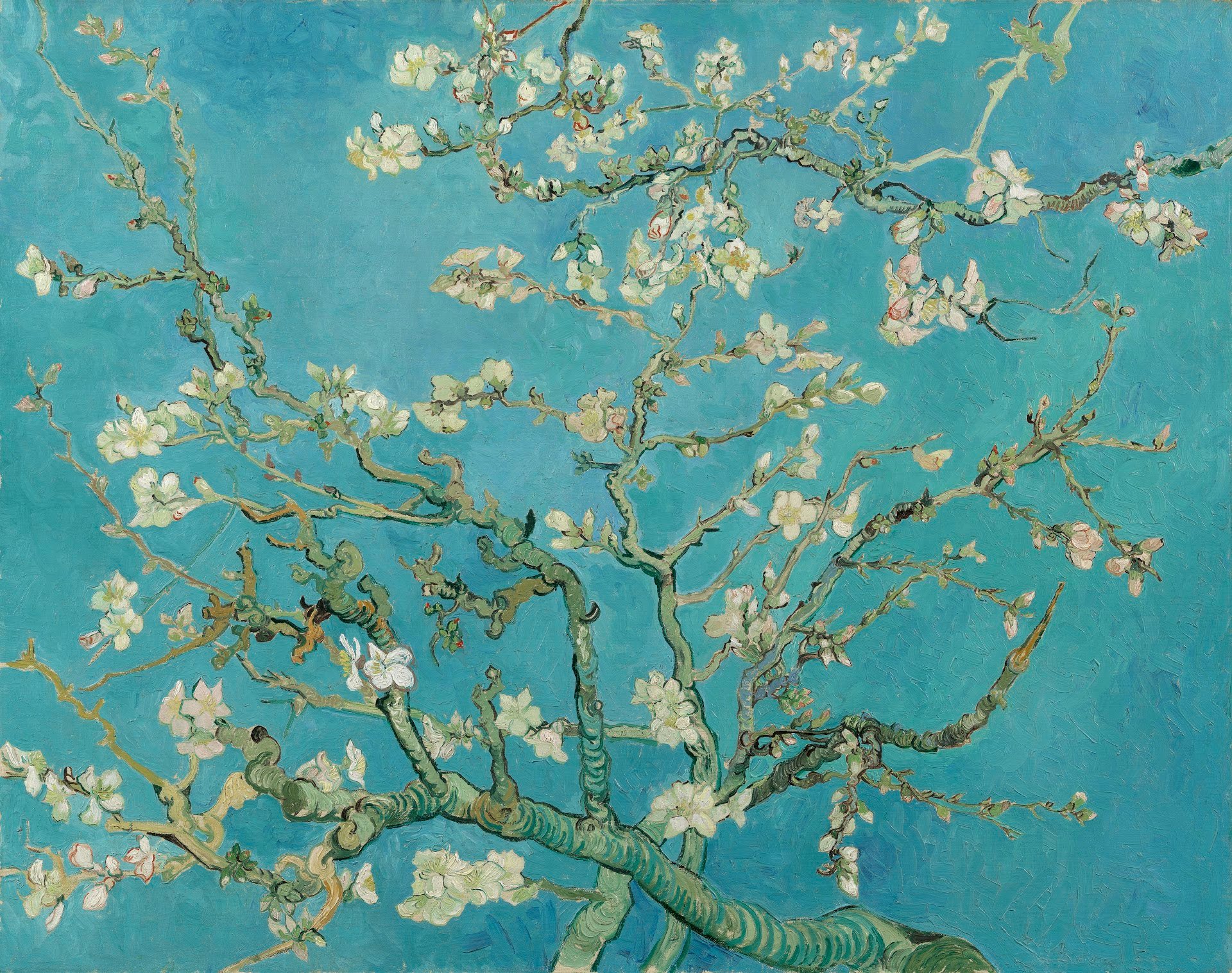

Van Gogh, Almond Blossom (1890), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh’s Almond Blossom had hung in Johan’s bedroom when he was a boy. He later admitted that it was a miracle that the picture was never damaged during pillow fights. A couple of years ago Johan told me that he felt it was among the artist’s “most important” works in what he still regarded was “our” collection—not in a legal sense, since it is now at the Van Gogh Museum, but in terms of the family heritage. Whenever Johan saw Almond Blossom he would recall that this exuberant picture of springtime had originally been lovingly painted to hang above his father’s crib.

The Second World War and the German occupation of the Netherlands brought a carefree childhood to an abrupt end. On 8 March 1945 Johan’s 24-year-old elder brother, also named Theo, was executed by the Gestapo. A Nazi official, Hanns Rauter, had been attacked in the Netherlands and, as a reprisal, over 250 Dutch resistance members were shot. Theo was among those selected to face the firing squad.

After the war Johan joined the Domestic Security Service, now known as the General Intelligence and Security Service. Even after retirement, he would say little about what he did, but his work involved dealing with the covert Soviet threat to the Netherlands at the height of the Cold War.

Tragedy struck the family once again on 2 November 2004. Johan’s 47-year-old son (yet another Theo), a controversial film director, was murdered. Theo had made a film entitled Submission, which criticised the treatment of women under Islam, and this provoked protests from the Muslim community in the Netherlands. While cycling to work in Amsterdam he was shot and stabbed by Mohammed Bouyeri, a Dutch-Moroccan Muslim.

Johan’s lasting legacy was to support his father, the Engineer, in a plan to help create a museum dedicated to Van Gogh. In 1962 the Engineer made an agreement with the Dutch government to hand over around 200 paintings and 400 drawings to a foundation. This was in return for 15 million guilders (the equivalent of €7m), even then a fraction of their market value. Today quite a number of the paintings would be worth over €100m each on the open market, so the whole collection must now be valued at many billions of euros.

The family made the right decision. Owning billions of euros worth of Van Goghs would probably not have brought happiness, but rather worries, and Johan rightly always had privileged access to see the paintings in the museum. From 1984 to 1995 he served as president of the Van Gogh Foundation, the legal entity that now owns the family collection.

An almond tree near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, probably the one once painted by Van Gogh, 2017, reproduced in Martin Bailey, Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, p. 15 © Martin Bailey

A few months ago I surprised Johan by sending him a dried leaf from what could well be the almond tree that had produced the blossom which Van Gogh had painted in 1890. The location of the tree, which was shown to me by two well-informed elderly residents of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, needed to be kept secret. Johan asked why this was necessary. One of Johan’s children had to tell him that Van Gogh is now so popular that swarms of tourists might endanger the life of this tree.

When Johan was born in 1922 Van Gogh, who had failed to sell his work, was only just beginning to become known. Johan’s lifetime marked the period when Vincent’s rise to fame has arguably made him the world’s most popular artist. Johan, a man of modesty, could never really quite believe that his great-uncle is quite so famous—and that even the painter’s venerable almond tree needs protection.

- On Saturday

- On Sunday Houston’s