Tate has released documents under the Freedom of Information Act to The Art Newspaper detailing how it was thwarted in acquiring a set of newly discovered William Blake watercolours. Now dispersed all around the world, seven of the works have been borrowed for its exhibition, which opens on Wednesday.

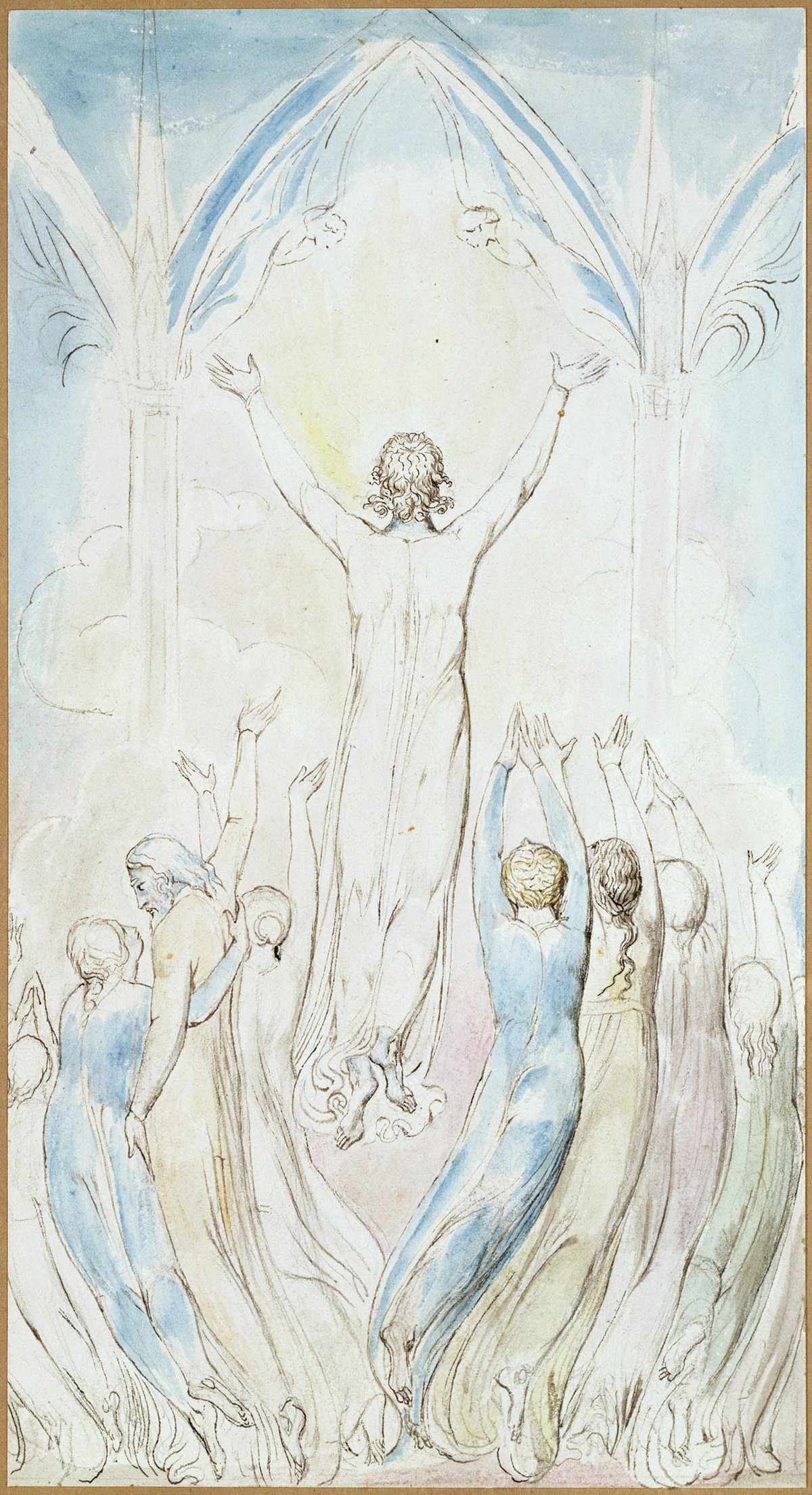

Three of the watercolours are on loan from the American collector and Blake scholar Robert Essick, two from unnamed private collectors and one each from the Louvre in Paris and the Huntington Art Collections in San Marino, California. The exhibition’s co-curator Amy Concannon calls them “the most well-known of Blake’s productions and the work which defined his posthumous reputation”.

The complete set of 19 watercolours was painted by Blake in 1805 to illustrate Robert Blair’s poem The Grave. Last exhibited in the 1830s, the portfolio turned up in a Glasgow bookshop in 2001; unrecognised as original works of art, the watercolours sold for just a few hundred pounds.

The Tate was desperate to buy them, as its trustee meeting minutes reveal—the former keeper Martin Butlin describes them as “the greatest discovery during his career as a Blake scholar (some 45 years)”. In 2002 the trustees agreed to buy them for £4.2m.

But as the deal was being struck, a dispute over ownership erupted between parties involved in the original purchase, putting the Tate’s acquisition on hold. The watercolours were kept at the Tate for safekeeping but after the dispute was settled by arbitration, the gallery was told to hand them over to an overseas owner, who had bought them for slightly more than £4.2m.

The minutes of the Tate trustees state: “The agent acting for one of the disputants ... negotiated a private sale to one of her foreign clients and Tate was denied the opportunity to make a counter offer.” The agent’s name is later recorded in the newly released records as the London dealer Libby Howie, who told The Art Newspaper that she had not been acting as an agent, but had offered informal, unpaid, advice—and that the Tate could have made a counter offer, although she says they did not.

A UK export licence application was subsequently submitted, with the applicant arguing that their value had increased and they were now worth £8.8m. This meant that Tate then had the opportunity to match that sum to acquire them. But, faced with this daunting price, its efforts to raise the money ended in failure. An export licence was therefore granted in October 2005.

In March 2006 the Tate trustees were told that Howie had been more than an adviser for a foreign purchaser. The minutes of the meeting stated that there “had never been a ‘private client’, but that she [Howie] had bought the works with her investors”. Howie disputes this: she says she had no share in the purchase and had advised a single overseas client, who had started an art investment group, so that he bought the works entirely with his own funds.

Howie was later entrusted with the sale of the portfolio but could not find a buyer at an acceptable price. The owner then decided to break up the set and sell the works individually at auction, at Sotheby’s New York in May 2006. Leon Black, the New York private equity boss and major collector, was privately approached by the Tate to buy the whole set, in the hope this would keep them together and eventually result in the portfolio being left to the gallery. This initiative never got off the ground.

At the auction, 11 of the watercolours sold for $6.2m (then £3.4m), around half the estimate for all 19. It is not known how the remaining eight unsold works were sold, but the dispersed 19 would not have fetched as much as the £8.8m export-deferral price at which they had then been offered to the Tate.

Nicholas Serota, the Tate’s former director, says: “It’s such a sad story. Together they were worth so much more, in every sense, than the sum of their fragmented parts.”

• William Blake, Tate Britain, London, 11 September - 2 February 2020