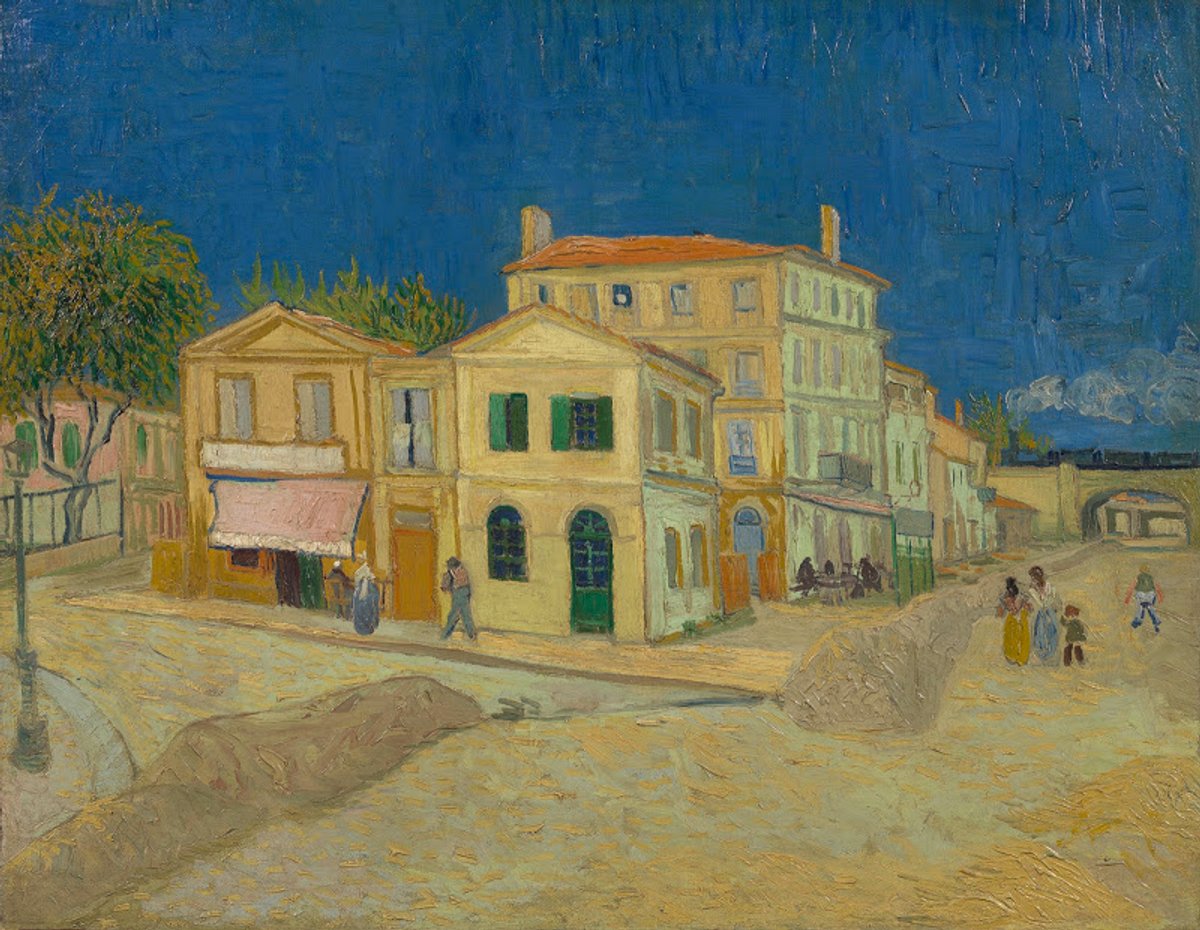

On 1 May 1888 Vincent van Gogh signed a lease for the Yellow House in Arles. On that day, 132 years ago, he wrote to his brother Theo in great excitement: “Today I rented the right-hand wing of this building… It’s painted yellow outside, whitewashed inside — in the full sunshine.” There he would paint his greatest pictures, including the Sunflowers.

Vincent had spent most of his adult life living in single rooms, garret accommodation and cheap hotels, but now he had an entire, cosy, semi-detached house. Downstairs there was a kitchen and a sitting room, which together would serve as his studio, with two bedrooms upstairs. Although built less than 40 years earlier, the house was not in the best condition and the rent was modest.

Vincent van Gogh’s Path in the Park (1888) Courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

The house at 2 Place Lamartine, in the Provençal town of Arles, was set on the edge of a large square with a public garden in the centre, which he soon painted in a group of canvases. As Vincent wrote to Theo, “the delightful thing about this studio is the gardens opposite”.

Although Van Gogh’s paintings give an impression of an almost bucolic urban setting, his new home was actually located in an insalubrious quarter—between an all-night café and the main police station. The house also lay halfway between the railway station and the brothels in what Van Gogh called “the street of the kind girls”. Trains ran on two viaducts very close to the Yellow House so the area would have been noisy at all hours.

Van Gogh’s life revolved around Place Lamartine, much of which can be seen in his vibrant painting of The Yellow House (1888), set under a deep blue sky. Next door, under the awning, was a grocery shop run by François and Marguerite Crévoulin, a convenient place to buy necessities. Further to the left, in the pink building behind a tree, was the restaurant of 70-year-old Marguerite Vénissac, where Van Gogh took his suppers. Beyond that, further to the left (but just outside the painting), was the all-night Café de la Gare, which he patronised. On the right side of the painting, the Route de Tarascon runs into the countryside where Van Gogh created some of his finest landscapes.

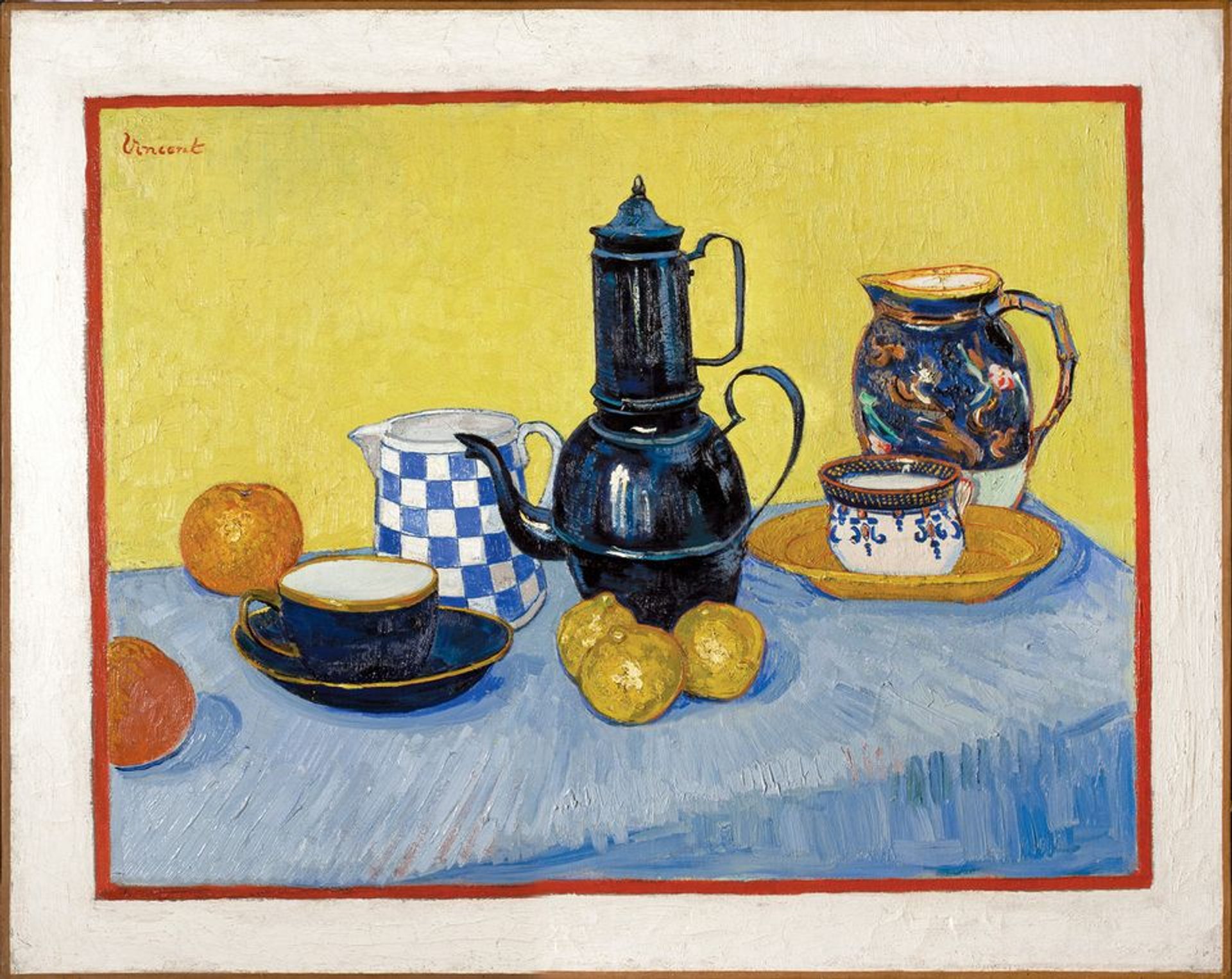

Behind its green front door Vincent enjoyed settling down to work in his new home, which offered plenty of space to spread out his materials. He immediately bought “what I need to make a little coffee or broth at home, and two chairs and a table”. A few days later he completed Still Life with Coffee Pot (1888), a scene of contented domesticity.

Vincent van Gogh’s Still life with Coffee Pot (1888) Courtesy of Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation collection, Athens; photo: Chris Doulgeris

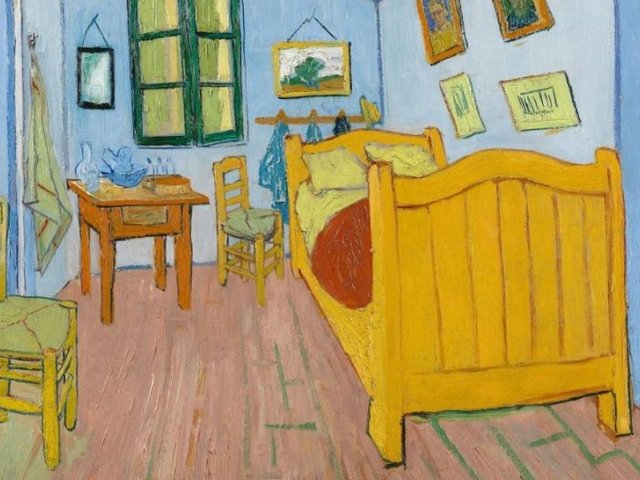

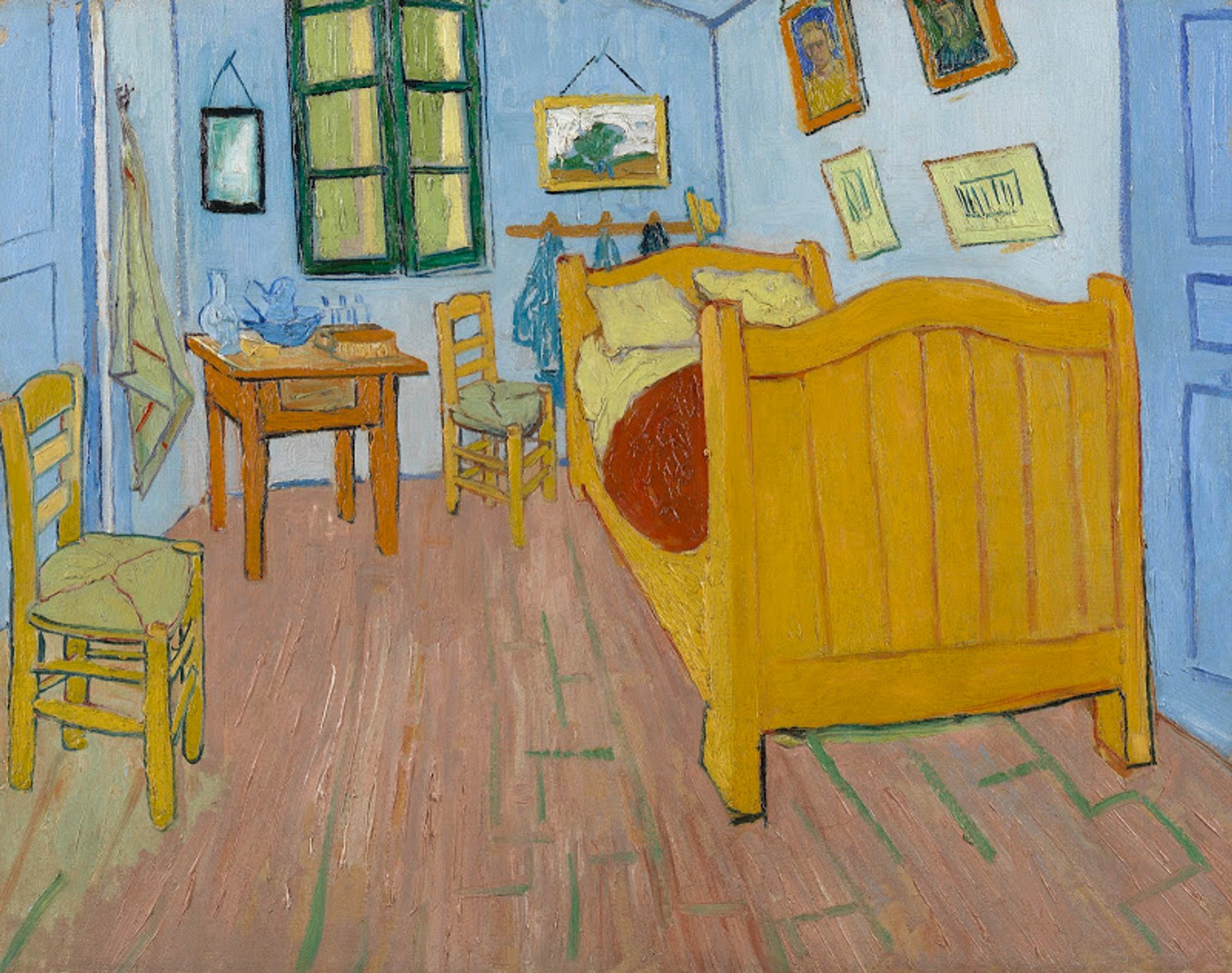

Vincent did not immediately sleep in the Yellow House, but instead took a room at the nearby Café de la Gare. He told Theo that he did not have enough money to buy a bed, but it is astonishing that he did not simply get a mattress and put it on the floor, rather than paying for his room at the café. By September he had bought two beds, one for himself and another for the guestroom. He then wrote to his sister Wil, “I can live and breathe, and think and paint”.

A month later Van Gogh made a painting of his newly furnished bedroom, a scene capturing his delight at the domestic arrangements. He intended the picture to be “suggestive… of rest or of sleep”.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Bedroom (1888) Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh wanted to share the Yellow House with an avant-garde artist from Paris, thinking it would be congenial and help reduce costs. His first choice was Paul Gauguin who, after some cajoling, arrived in late October. Initially they set up their easels next to one another, tackling the same motifs, and indulged in long discussions on art late into the night. But as the weeks passed, tensions developed and their collaboration was brought to an abrupt end when Van Gogh mutilated his ear on 23 December 1888.

Van Gogh’s dream of a shared “studio in the South” was over. For the next few months he was in and out of hospital, sleeping in the ward most nights. By the spring of 1889 he realised that he could not manage to live independently. With great reluctance, he gave up the Yellow House lease on 30 April and moved to the mental asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

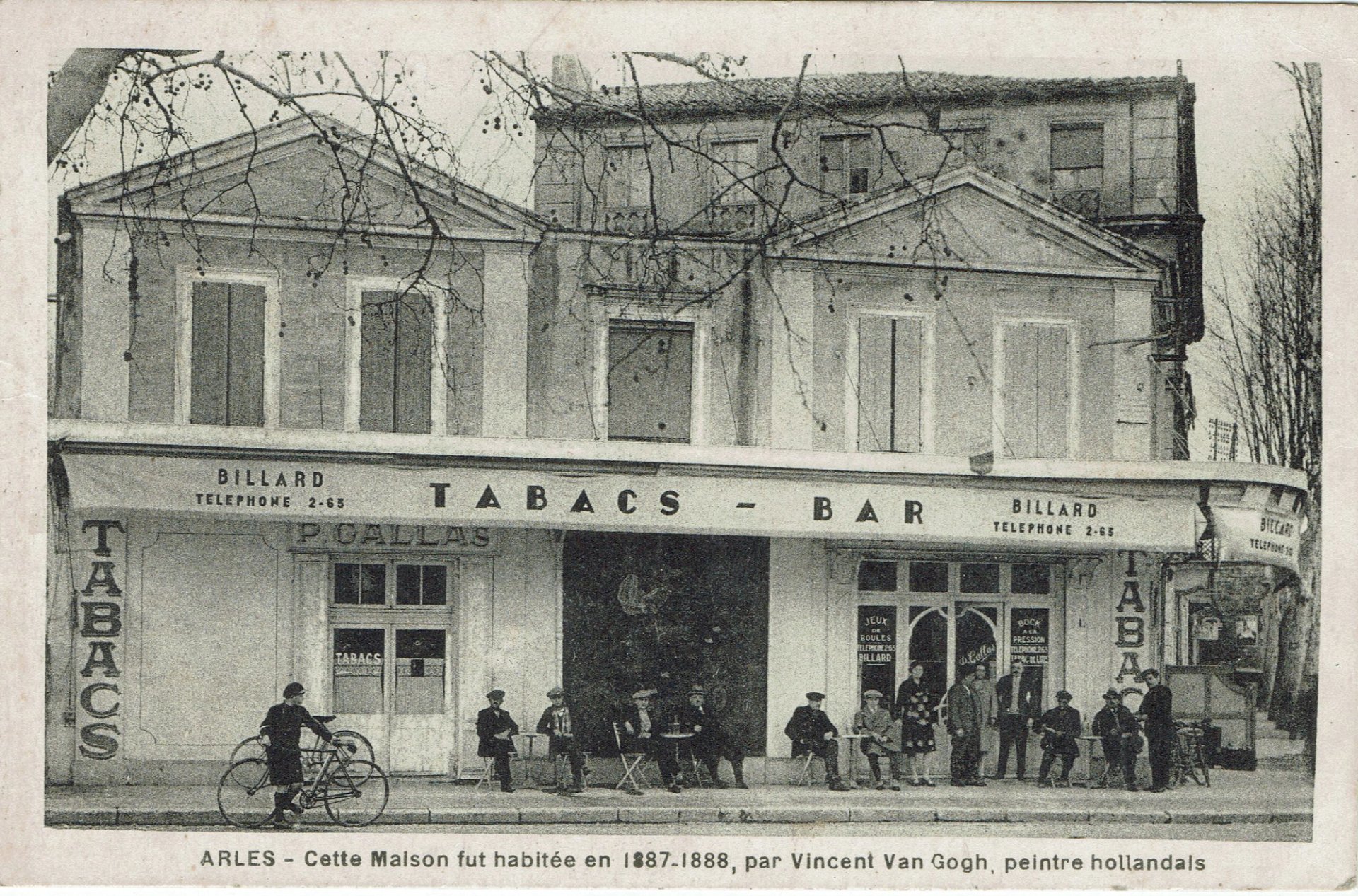

Postcard of The Yellow House, late 1920s

And what was the fate of the Yellow House? The adjacent grocery shop was turned into a café a few years later and in the late 1920s it was extended to include the ground floor of the Yellow House. With Van Gogh’s growing fame, a stone plaque had been put up on the building in 1922, although the wrong dates for his stay were incised (1887-88, rather than the correct 1888-89). In 1937 there was talk of setting up a small museum in the Yellow House, but the war intervened.

Sadly, the Yellow House was hit during an Allied bombing raid on Arles in June 1944. Van Gogh’s bedroom was destroyed, although Gauguin’s room partially survived. The walls of Van Gogh’s former studio downstairs suffered less damage. The Yellow House could have been rebuilt, but it was simply demolished. Even the plaque was lost.

Had the Yellow House survived, it would almost certainly now be one of France’s most popular tourist attractions outside of Paris. Many millions of visitors would have swarmed to Arles, anxious to see the place where Van Gogh created his most exuberant canvases. But we still have his painting of The Yellow House to remind of us of what was achieved behind its welcoming walls.