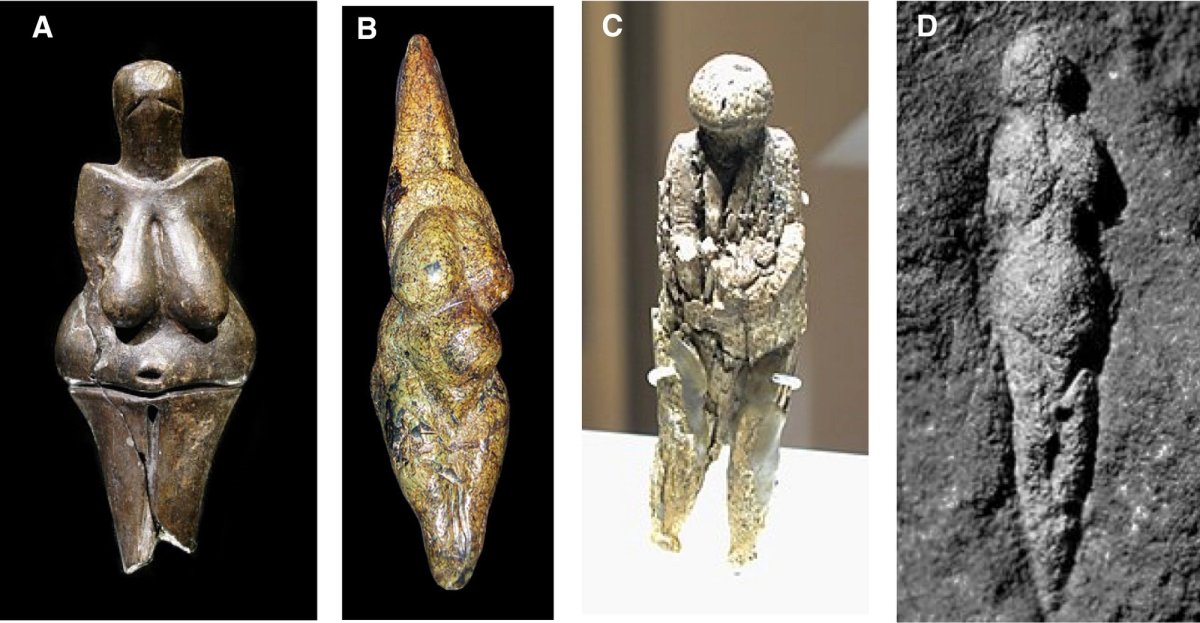

Venus figurines were symbols of survival, representing an ideal that helped prehistoric Europeans through phases of starvation and climatic change, write researchers in the journal Obesity. The figurines, which depict obese or pregnant women, were created in Europe during the last Ice Age, between 38,000 and 14,000 years ago, making them among the world’s earliest art. Most are generally big enough to be held in one hand and some appear to have been worn as amulets. Scholars have long debated the figurines’ meaning, arguing that they represented fertility or beauty, or even goddesses, but with little proof.

Now, researchers based at the University of Colorado and the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates say that the figurines can only be understood by looking at the climatic and environmental changes that Europe’s hunter-gatherers experienced during the Ice Age—a time of freezing temperatures, advancing ice sheets, and starvation. “We hypothesize that the figurines were meant to enhance survival of the hunting and gathering band,” write the researchers in the article. “Especially during pregnancy, obesity helped assure survival during episodes of severe food shortage.”

The researchers measured the Venus figurines’ waist-hip and waist-shoulder ratios, and found that those created closest to Europe’s advancing glaciers were more obese than those from further south. Figurines carved when the glaciers retreated were also less obese. “Thus, as people experienced nutritional stress, they carved fatter figurines and depicted leaner figurines when securing food became more predictable,” the researchers write. This led them to propose that the figurines “conveyed ideals in body size for young women and especially for those who lived in proximity to glaciers.” Once used, the figurines seem to have been passed down from generation to generation as an “ideological tool”.

The figurines may also have had a magical significance to Europe’s hunter-gatherers, as they were perhaps held by women to help them gain weight, the researchers write. “The figurine would represent a desired likeness of the woman in which the image had power to bring about a healthier mother and child, spanning conception, a precarious pregnancy, childbirth, and nursing.”