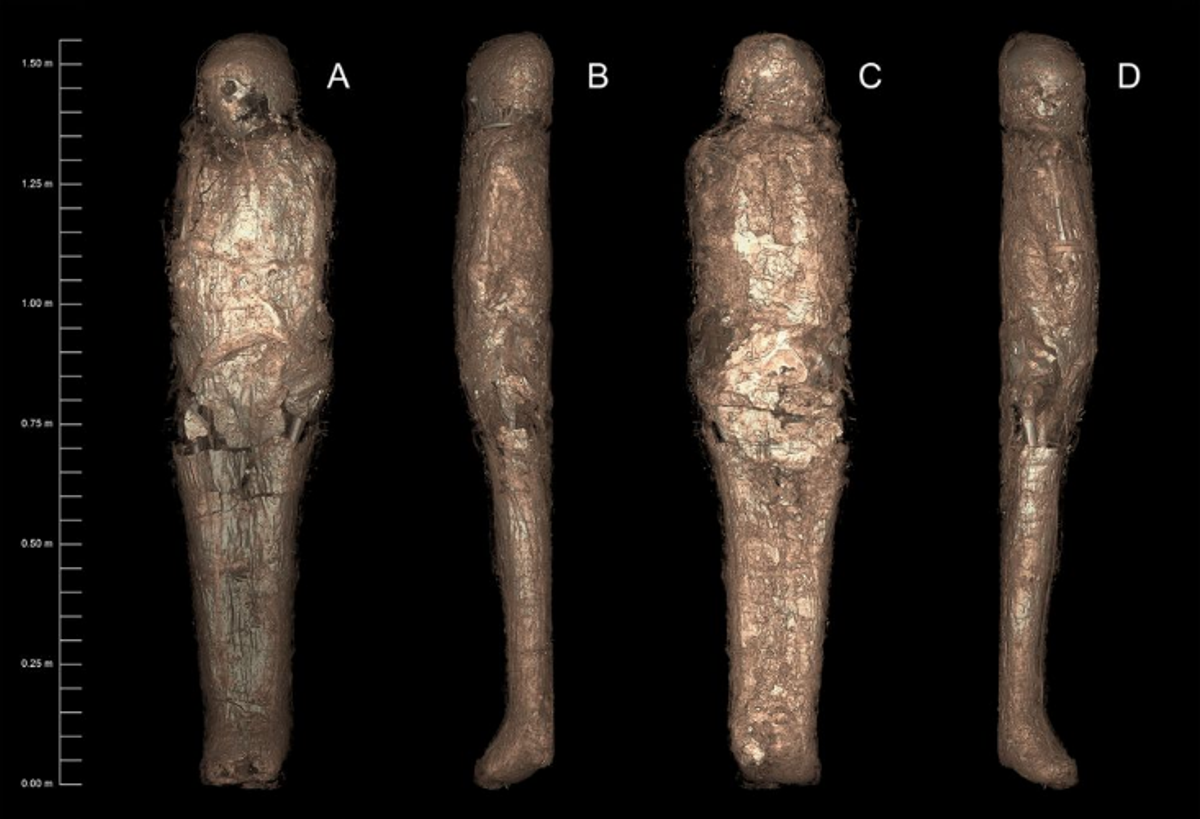

An ancient Egyptian mummy’s painted mud shell may have been a budget-conscious way of copying elite embalming methods, write researchers in the science journal Plos One. The shell, found under the mummy’s wrappings, was first identified in 1999, but has only now been fully revealed thanks to modern CT scans. It covers the entire body, and was painted white over the head and red over the face. The study also revealed that the mummy—held in the collection of the Chau Chak Wing Museum in Sydney, Australia—is probably that of a woman, who was 26 to 35 years old when she died around 1200-1113 BC.

No other mummy is known to have been encased in a mud shell, though the bodies of elite Egyptians, and particularly kings, could be covered in a layer of resin, which produced similar results. “People of lesser means had more limited recourse to expensive imported resins, especially in the quantities needed to create a protective shell over the body,” write the researchers in the article. “However, emulation of elite burial practices could be attained through the use of cheaper, locally available alternatives.” The shell’s discovery may lead to further, similar examples being identified or confirmed in the wrappings of other Egyptian mummies.

Mummified individual and coffin in the Nicholson Collection of the Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney Photo: Sowada et al, PLOS ONE, with permission from the Chau Chak Wing Museum, original copyright 2019

The shell also had a practical and religious function. Decades after its original wrapping and burial, the mummy was damaged, perhaps by tomb robbers, and became disarticulated. When rewrapping the body, embalmers may have added the shell to help hold it together—a preserved and whole body being necessary for an afterlife existence, according to Egyptian funerary belief. The researchers also showed that the mummy is over a century older than the coffin it rested inside. Bought in the mid-19th century, most likely in Luxor, the mummy was probably put in an empty coffin by antiquities dealers, who could make more money by selling them together.