In July 2020, during a general meeting for staff at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Richard Armstrong, the director, pledged to “extend my [salary] reduction as long as necessary”. Armstrong promised to cut his own earning while seeking to justify the need to lay off 11% of the contracted workforce in the wake of the “devastating impact” of Covid-19 measures. In all, 24 workers lost their employment outright, while an additional eight people accepted voluntary separation packages.

In fact, Armstrong would soon pocket a massive increase in take-home pay. Recent public records revealed Armstrong’s earnings swelled by more than $400,000 between 2019 and 2020, a real-terms pay increase of more than 40%.

The leadership of the museum appears to have privately done the exact opposite of what it pledged to do in public. In its defence, the museum stated that Armstrong’s pay increase was due to “deferred compensation”—part of his multi-year contract determined by the board in 2019, which allows employees to collect income at a later date. Still, the timing was awkward.

At the end of the day, working in the arts or a non-profit is still a job. You can’t eat prestigeCatie Rutledge, Art Institute of Chicago

Once upon a time, a person of Armstrong’s standing might have hoped that the figures, buried in the Guggenheim’s 990 IRS filings, would simply be quietly filed away in the dusty recesses of a public archive. But A Better Guggenheim, a newly emergent union of staff members who organise anonymously, evade detection and are native digital operators, made sure the particulars of Armstrong’s remuneration went viral.

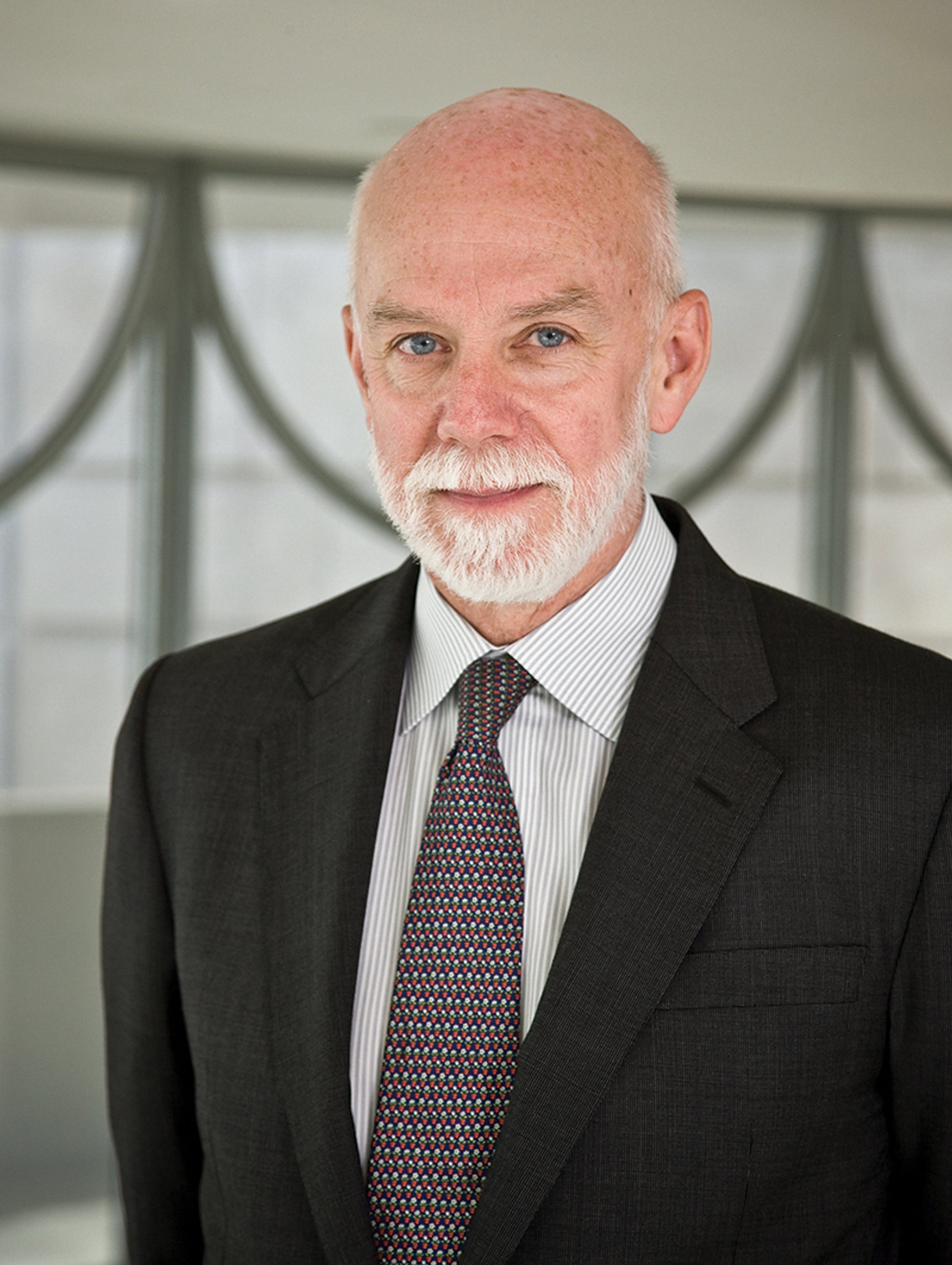

In 2019/20, the Guggenheim’s Richard Armstrong enjoyed an increase of $400,000 Photo: David M. Heald, © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, NY

A Better Guggenheim is not unique. It seems that a virulent strain of unionism, born out of lockdown and pressingly of the moment, has swept the US’s museum sector. This is a new form of collective action: remotely formed, digitally optimised, fluent in social communications, diverse in composition and intent on overturning long-held status quos around labour rights, job security and working conditions. These new unions often work in harmony with more traditional and historic ones. As well as collective bargaining and negotiation with employees, they seek to support anonymous whistleblowers, increase transparency and push for social justice.

Sense of urgency

They amount to “a new renaissance in the union movement of America”, says Tom Finkelpearl, the former cultural commissioner of New York City. “Unions are being discussed more seriously now than at any other time in my adult life,” he says. “We’re seeing a widespread embrace of the idea of labour justice in the museum sector. There’s a new sense of urgency about job safety, job security and job quality. Reasonable expectations are changing, and people are beginning to realise they have routes of recourse.”

This new movement is, in part, a reaction to Covid-19. Lockdown measures meant ticket sales and commercial revenues dramatically ground to a halt in March 2020, leading many museums to furlough staff before resorting to swingeing redundancy drives to balance budgets. Staff numbers have been cut in some instances by up to 75%. Many major US institutions accepted support through the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program; the Guggenheim, for example, received a $5.9m loan, also listed in its IRS filings.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Museum workers lucky enough to keep their jobs now face stagnating wages, loss of labour rights and poor health and safety conditions. The 2020 median annual wage for archivists, curators and museum workers was $52,140, according to the Labor Statistics Bureau. It is unlikely that that figure has risen significantly throughout the course of the pandemic. Yet inflation in the US is at its highest in decades; as of December 2021, the annual rate stood at 7%, up from 1.4% in December 2020.

A report by the American Alliance of Museums, published in April 2021, found that museums closed to the public for an average of 28 weeks during 2020. More than 75% of those surveyed stated that their income fell by an average of 40% that year, while 56% went through rounds of layoffs and furloughs. Rehiring, in most cases, is off the table. Those who kept their positions have had to pick up the slack.

Yet there is little to suggest that museum revenues will bounce back any time soon. The Omicron variant of coronavirus has meant that many institutions have had to limit hours, impose onerous new safety guidelines and curtail revenue-making trade once again. Some have been forced to close due to staff shortages, depriving those who have not fallen victim to the virus from earning a day’s pay.

Wave of unionisation

Resultant unionisation pushes are almost too numerous to count. Last month, the Jewish Museum in New York filed a petition for union elections with the National Labor Relations Board via representatives from the United Auto Workers union (UAW). Concurrently, employees at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) and the AIC museum also voted to unionise with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). In a statement, Anders Lindall, an AFSCME trade unionist, hailed “a wave of cultural workers organising from coast to coast”, while Catie Rutledge, AIC’s coordinator of philanthropy, said: “At the end of the day, working in the arts or a non-profit is still a job. You can’t eat prestige.”

View of the Michigan Avenue Entrance at the Art Institute of Chicago. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

The UAW, one of the most historic unions in the US, remains a significant player in the museum sector. Last August, staff at the Brooklyn Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art and New York’s Hispanic Society Museum and Library all voted to unionise with UAW Local 2110.

Beyond the traditional union stronghold of New York, the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Museum of Tolerance and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art have all voted to unionise, too.

Unionising efforts were already taking place before Covid, but the pandemic has sent the figures into overdrive. “It’s changed everything,” Finkelpearl says. According to the Union Membership and Coverage Database, 13% of museums were unionised in 2020. While this figure appears low, it was actually the highest level since 2013.

Maida Rosenstein, the president of UAW’s Local 2110, says: “When the pandemic hit, we were concerned it would shut down organising. But it actually spurred more organising. People felt the need to reach out to each other, even if not in person, and find ways to work together and organise remotely. The digital society made this possible.”

This new strain of unionism is often peopled by a new demographic of museum worker, one more politicised, younger and more diverse than previous generations. Yet it is also one saddled with high levels of student debt and having to contend with astronomical living costs.

“Traditionally, museums have been staffed by people who didn’t actually need to make that much money from their work,” Finkelpearl says. “But a big demographic shift is taking place amongst many museum workforces. That is resulting in new ways of organising amongst existing unions, and new types of unions emerging.”

The lockdown exposed stress fractures that already existed. In the relative boom years before the pandemic, museum workers watched as their places of work embarked on aggressive expansion schemes, even as working conditions worsened. “Workers saw tremendous, ever-widening wage inequalities in their workplaces: boards of trustees composed of billionaires, money pouring in from other billionaires, huge sums spent on massive construction projects, museum leadership salaries going up,” Rosenstein says. “And yet, at the same time, the word to the staff was: ‘You’re lucky to be working here, you should not expect anything, and you cannot demand any security in your job’.”

The social justice movements that spread across US culture in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 have also played a huge role in the union movement. The solidarity messages many institutions published in the wake of Floyd’s death “have meant the management of many museums have become trapped in their own rhetoric”, Finkelpearl says. “If you define yourself as a progressive social justice institution, and you write this rhetoric down, it’s then difficult to oppose your workers when they ask for improved rights.”

But a challenge remains for traditional unions. Prior to the pandemic, many museum leaders actively sought to employ gig workers, even for integral roles. “They actively created a precarious workforce who were part time, on call and earning minimum wage,” Rosenstein says. “They had no benefits or job security, and they were the first to go after the pandemic hit.”

This was particularly the case in many museums’ outreach and educational departments. “These programmes were almost entirely populated by part-time, contract educators,” Finkelpearl says. "Many of them were younger and more diverse than the rest of the museum staff. Many of them were female and of colour. And they all got cut, even as museums pledged to increase their educational programmes and be more responsive to their communities in the wake of the George Floyd protests. Museums decided to protect their full-time staff but cut the contractors.”

But can unions, as they traditionally existed, properly represent the interests of this new demographic of worker? Lise Soskolne, the core organiser of campaigning group Working Artists and the Greater Economy (WAGE) is not so sure. WAGE is a data-driven tool that attempts to assist supply-chain, independent arts workers who struggle to gain representation from old-school unions.

“I imagine there are advantages that come with the power of a union like UAW,” Soskolne says. “But there are also disadvantages, such as the lack of direct action or involvement workers have once they unionise, not to mention the discrimination that has historically been endemic to some unions.”

Soskolne is careful not to define WAGE as a traditional union, even though it shares similar aspirations around labour organising, campaigning and collective bargaining. In her dealings with traditional unions, Soskolne was “struck by a sometimes myopic focus on numbers”. And, beyond the progressive Left, many Americans retain “an allergy to unionism”, she says.

In the art world, there are certain advantages to freelance working life. “That’s especially true if you’re a practising artist with a secondary income because you need flexibility,” Soskolne says. “The Left loves to hate on freelance work, but there are a lot of good things about it. Unions have struggled to represent independent gig workers, and I want to understand why,” she says.

“That, I think, is why this new form of solidarity unionism is such an important alternative.”