The idea that museums can sell NFTs and digital reproductions of works in their collection initially sounds very attractive. It seems to solve two problems in one swoop.

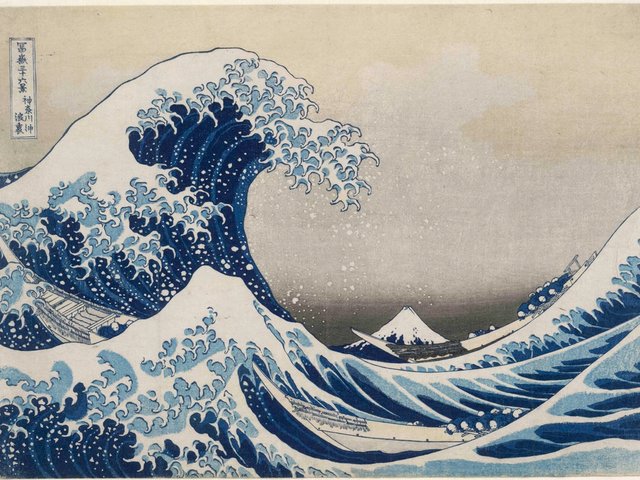

First, it raises much-needed money for cash-strapped institutions...and by using an asset they cannot otherwise monetise. So the British Museum is selling NFTs of Hokusai’s The Great Wave (1831) and Turner watercolours, costing between €500 and €4,999 (gulp), all organised by the French company La Collection—and you can even pay in Ether (ETH) if you like.

Meanwhile, four Italian museums including the Uffizi have authorised digital reproductions of works in their collections, for instance Raphael’s Madonna of the Goldfinch (1508). Created by the Italian company Cinello, they cost between €100,000 and €250,000 (again, gulp) in editions of nine.

So what’s not to like? Speakers at a recent panel at Unit London gallery, which I moderated, were enthusiastic about the Italian digital reproductions, saying they would help museums, bring in new audiences and extend the reach of masterpieces far beyond those who are able to travel to see them in person.

But I remain deeply unconvinced by some aspects of the projects. Let’s start with the British Museum. In an extraordinary comment on its site, La Collection claims that “NFT ownership allows for your assets to exist in perpetuity...postcards and prints will likely fade over time but the vibrancy of NFTs remain.” And it continues: “NFTs are also extremely collectible and tradeable; it is much easier to resell an NFT than it would be to resell a postcard.”

Where to start? Ultimately, these are just digital posters. We know that a modern postcard of the Great Wave is not resaleable. So why should a digital image be more so? Answer: because it is an NFT and so a tradeable asset for as long as NFTs are still the fashion du jour. Indeed, there are already attempts to resell these NFTs: the French site Artprice has a Hokusai bought for €5,905 last year and is now seeking €148,000. And let’s not go down the path of how long this technology will even work—certainly not in perpetuity.

As for the Italian works, they are very beautiful digital reproductions, with lovely frames, but at powerful prices, apparently based on those for equivalent original works. No matter: apparently five have already sold. This makes no sense to me, since a copy of a Leonardo is not, intrinsically, worth more than a copy of a Modigliani.

A speaker at the panel even claimed that the experience of seeing them is “even better” than seeing the originals, which is worrying. Are we to believe that completely smooth, brightly lit and high-gloss digital screens images are “better”—in the same way that swirling enlarged Van Gogh experiences are “better”—than seeing the real thing?

It seems churlish to cavil and I am certainly delighted that museums can raise money in these ways. But while I think NFTs have a real place for today’s artists, enabling them to certify their creations and even profit on resale, I feel more conflicted about plundering the past in this way. Museums have a role and duty to collect and explain the objects of the past. They should be wary of allowing their precious holdings to be exploited for others’ gain in this way.

Art Market Eyecomment

NFTs of Old Masters—good or bad?

Are the digitally produced copies of museum works sold as NFTs for six-figure sums simply very expensive digital posters?

3 March 2022

© Illustration by Katherine Hardy

Art Market Eye

Georgina Adam, our editor-at-large, comments on major art market trends and their impact on the trade. Her column appears on the first Thursday of every month on our website and in our Art Market Eye newsletter in which our art market editors analyse the latest news and works coming up for sale. Sign-up here