Ancient art dating back to the Iron Age has been discovered by looters beneath a house in Turkey. The art, which is cut into a rock, was found in a hidden underground complex concealed beneath a domestic home in the remote village of Başbük, in south-eastern Turkey near the Syrian border.

Although the art was first uncovered by looters, the myriad complex of tunnels has now been studied by archaeologists after a rescue mission. They dated it to the first millennium BC—probably between 900 and 600 BC when the area, and much of the Near East, was controlled by the Neo-Assyrians.

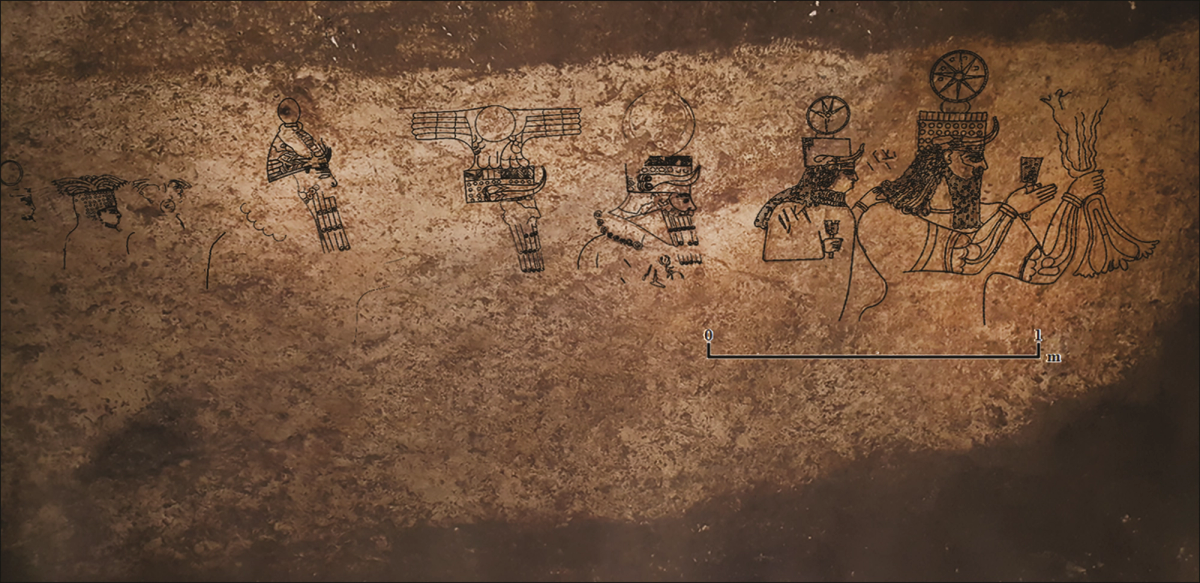

The artwork is incised across a 3.96m-long rock wall panel, with the outlines painted in black. It shows a procession of eight Syrian-Anatolian deities. They include the storm god Hadad, the main goddess of Syria, Atargatis, the moon god Sîn, and the sun god Šamaš, followed by others that are harder to identify. One Aramaic inscription may bear the name of a known Neo-Assyrian official, Mukīn-abūa, who perhaps controlled the region.

“[This rock wall panel] is the first known example of a Neo-Assyrian-period rock relief with Aramaic inscriptions, featuring unique, regional iconographic variations and Aramean religious themes,” the team writes in the research paper, published in the journal Antiquity.

Because the ancient artists only completed the figures’ upper bodies or heads, and left the space below untouched, it appears that the ancient work was never finished. This could be due to “regional unrest, a transition in power, or another reason affecting the work schedule,” the team writes.

Further research is needed to reveal more about the complex, which is more than 30m long and descends into the ground along rock-cut steps to a lower gallery, where further discoveries may await. Work is currently on hold while the authorities make the unstable tunnels safe.

“The processional panel, which would have greeted visitors in the upper gallery, has yet to yield all its secrets,” the team writes. “Başbük’s rock wall panel is among the few such reliefs found since the mid-nineteenth century and future excavations may uncover more.”