Billy Al Bengston, a painter known for his stylised, highly-finished paintings that feel plucked from the visual lexicon of California culture, has died, aged 88. He died in his longtime home in Venice, California. It was known that the artist was living with dementia, and last year CBS News reported when he was temporarily missing.

As much as he’s known for his iconic paintings—most recognisably the abstract, lacquered works with compositions that feature centered motifs such as a chevrons and hearts—he was also known in equal parts for his motorcycle racing, his charm, his friendships that spanned the networks of West Coast artists and his key role in the development of the Los Angeles art scene.

Bengston was among the first artists to show at Los Angeles’s historic Ferus Gallery, placing him alongside the likes of Ken Price (whom he surfed and shared a studio with), Ed Ruscha (who referred to Bengston as “a mentor”) and Edward Keinholz (who founded the gallery along with Walter Hopps in 1957). Ferus, which was active until 1966, broke ground in a number of ways, including being the first exhibition space to show Andy Warhol’s Campbell's Soup Cans (which were priced at $100 a canvas at the time).

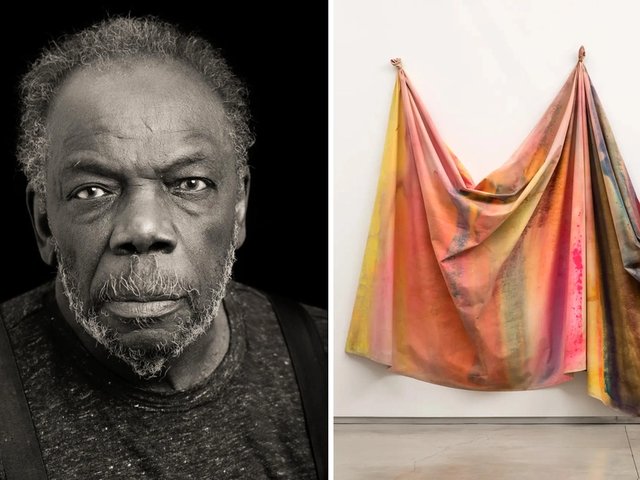

Billy Al Bengston, Ho Omalie (1982). Courtesy of Various Small Fires Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

By the mid-1960s, Bengston was using lacquer and enamel to achieve a look inspired by the finishes on cars and motorcycles. This left many of his paintings with a shining, almost reflective surface, causing some critics to categorise him among California’s Finish Fetish artists—a group known for the meticulously perfected, stylised surfaces of their paintings and sculptures—where his cohort included Larry Bell, Dewain Valentine, Judy Chicago, Joe Goode, Robert Irwin, John McCracken and others. Many of the Finish Fetish artists were also associated with Ferus Gallery. Bengston’s use of everyday motifs has also led critics to count him among the Pop Artists of the era.

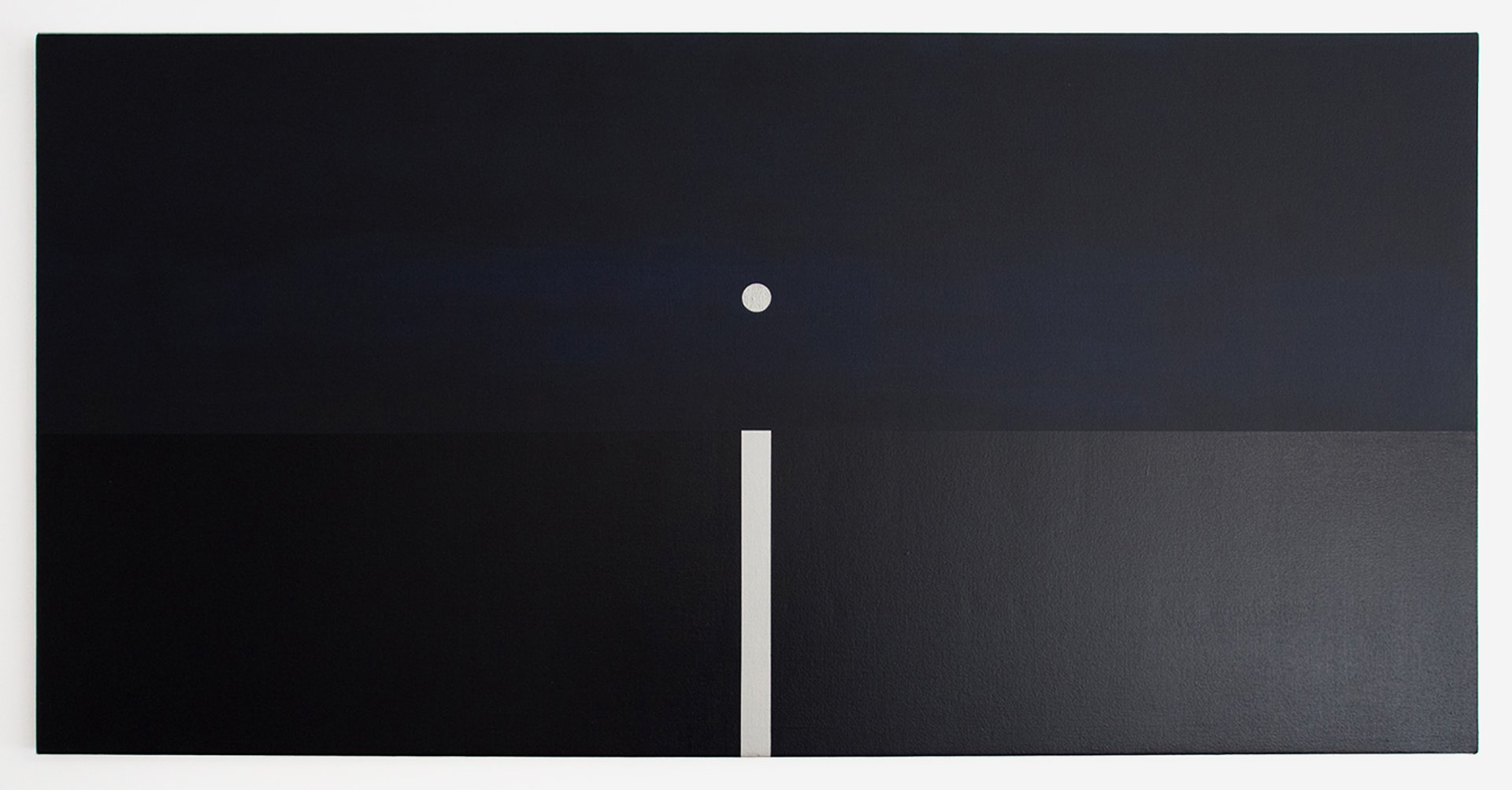

Billy Al Bengston, B'nE in SF (1989). Courtesy of Various Small Fires Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

Bengston was born in Dodge City, Kansas, in 1934. His family first came to Los Angeles in 1944 before returning to Kansas. In 1948, they once again relocated to Los Angeles, this time for good. His father was a tailor who also ran a dry cleaning business and his mother was a musician. “She was a child prodigy. She could sight-read and transpose on the piano when she was four years old. She could play every instrument in the orchestra, and she could sing best of all,” Bengston told Hyperallergic in 2016.

He went to Manual Arts High School in South Los Angeles, at the time the only high school in the country with an art department that used nude models. “I was pretty excited about this, until it happened,” he said in the same interview. “They were some of the ugliest people you’ve ever seen.”

He then attended Los Angeles City College for two years, studying “primarily ceramics and gymnastics” according to his website, followed by the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, where he studied under Richard Diebenkorn and Sabro Hasegawa, and then the Los Angeles Art Institute, where both he and Ken Price—who were already surfing buddies at this point—studied under ceramicist Peter Voulkos, though he didn’t graduate from either university. Bengston told Artforum in 1968 that Diebenkorn and Hasegawa were both “influences on me, with Diebenkorn showing me how I might physically approach painting and Hasegawa by his example as a person and thinker”. He said elsewhere that in Voulkos he found an artist and mentor whose creative energies were rigorous and energising in a manner he hadn’t yet encountered, but that he was ultimately dissuaded by Voulkos’s mastery of ceramics, feeling that he could never compare. This led him to ultimately abandon both the university and the medium, opting instead to pursue painting.

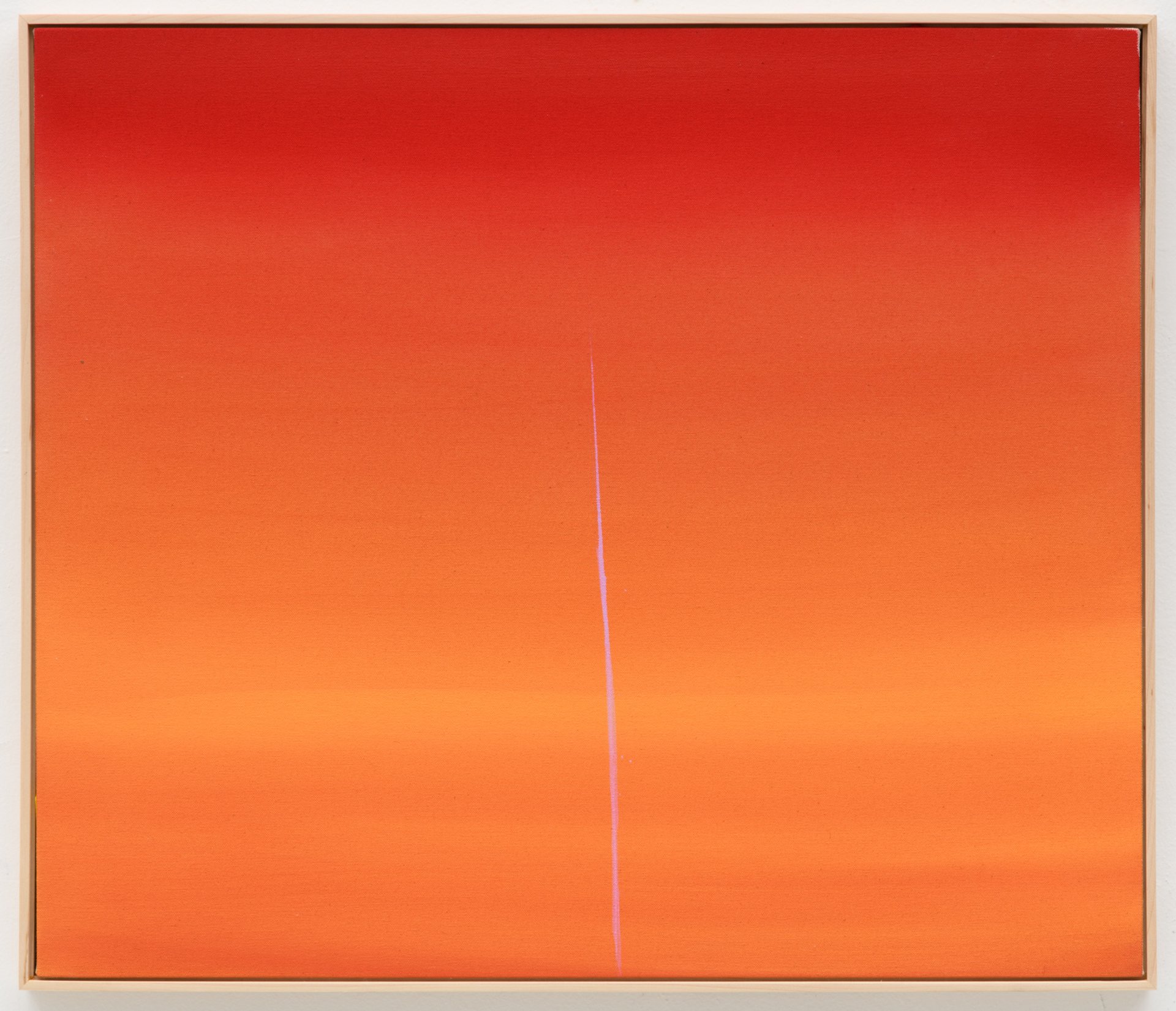

Billy Al Bengston, Y Tu Dinero Tambien (2001). Courtesy of Various Small Fires Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

“Billy Al is really the charter member and leader of LA’s ‘Cool School’, and a founder of the LA art scene in the 1960s,” collector and gallerist Adam Lindemann of Venus Over Manhattan told artnet News on the occasion of a 2016 show of Bengston’s work. “Motorcycle racer, surfer and inspired artist, he is one of the fabled heroic figures of the West Coast art scene.”

In 1958 he had his first exhibition at Ferus Gallery. “[I was] cruising around I ran into Ed Keinholz, who was up in Echo Park at the time. He opened a gallery on La Cienega Boulevard. It was a small space inside of the art theater. Then, with Walter Hopps, he opened Ferus Gallery,” Bengston said. “He would be in the back doing his thing. I’d take him a six-pack and we’d hang out. He said, ‘Want to have a show here?’ I said, ‘Sure.’” Bengston went on to have five solo shows at Ferus.

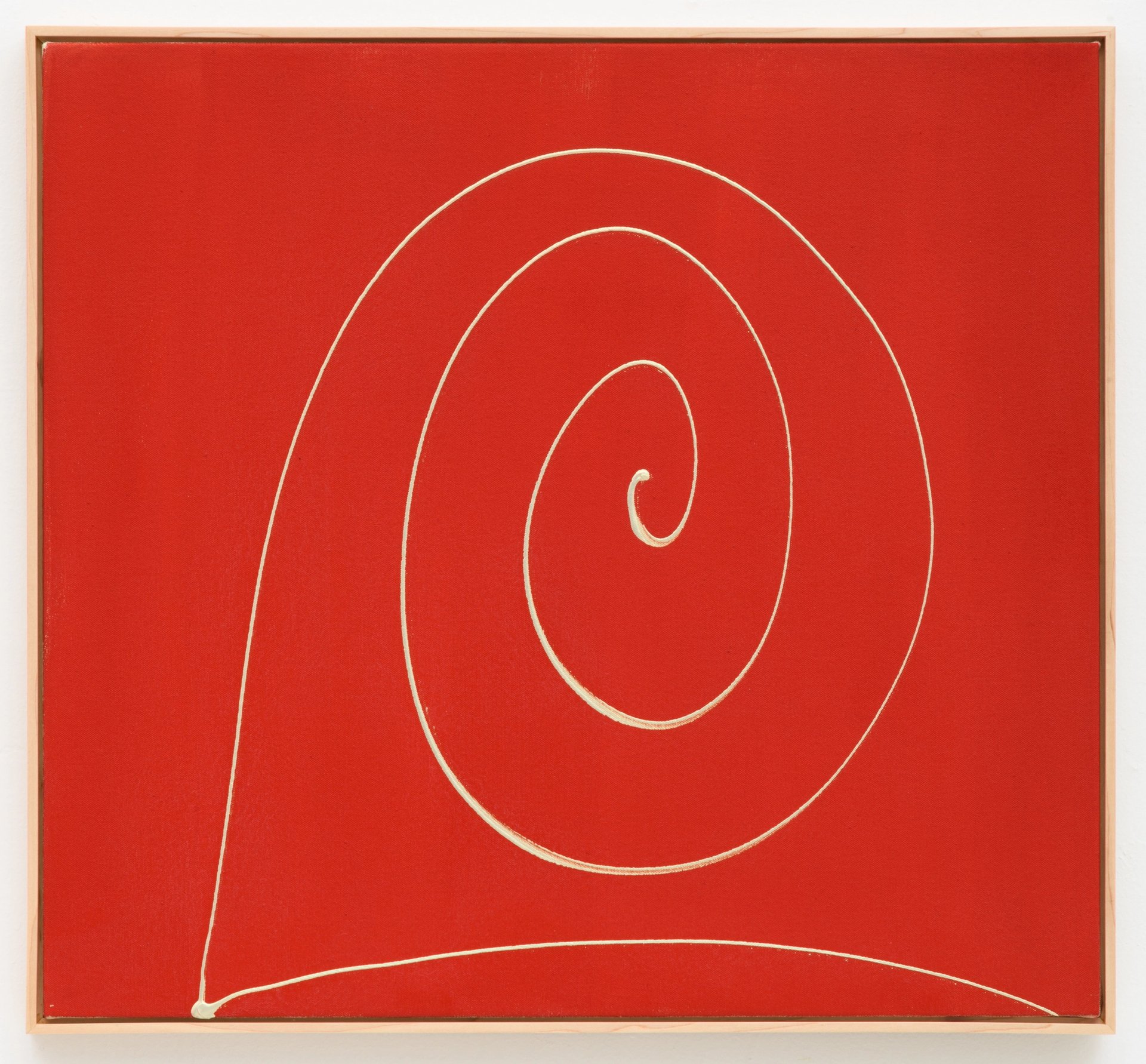

Billy Al Bengston, Kim (2020). Courtesy of Various Small Fires Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

In 1968, Bengston had a solo-show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma). A not-yet-established Frank Gehry designed the installation for the show. According to the Los Angeles Times, Gehry said that Bengston “welcomed me in as an artist to his world, when I was just starting out. That was really important to me—I was invited into the family.”

In a review of the 1968 Lacma show published in Artforum, James Monte wrote: “Perhaps the most difficult aspect of Bengston’s oeuvre is that the pictures themselves refuse to become either wholly abstract or wholly figurative. The difficulty, of course, exists in the mind of the viewer and not in the paintings themselves. A first viewing of a body of Bengston’s work is puzzling because one is astounded at the richness of their brushed, lacquered and polished surfaces,” adding, “Bengston suppresses a tendency toward the overt depiction of malignancy and instead metes out the emotive force carefully, serialises it, sets restrictive limits on its use and in other ways regulates it. By engineering or manipulating the uses to which psychic malevolence is used in art, by juxtaposing it with humor or playfulness, the artist is able to domesticate or at least sublimate this virulence to a great degree.”

Billy Al Bengston, Bruce (2020). Courtesy of Various Small Fires Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

A great number of museum shows followed, including a 1988 survey also held at Lacma. Today Bengston’s work is in museum holdings throughout the US and Europe. “His passing has left a huge hole in me,” Wendy, his wife, told the Los Angeles Times. “But he belonged to everyone.”