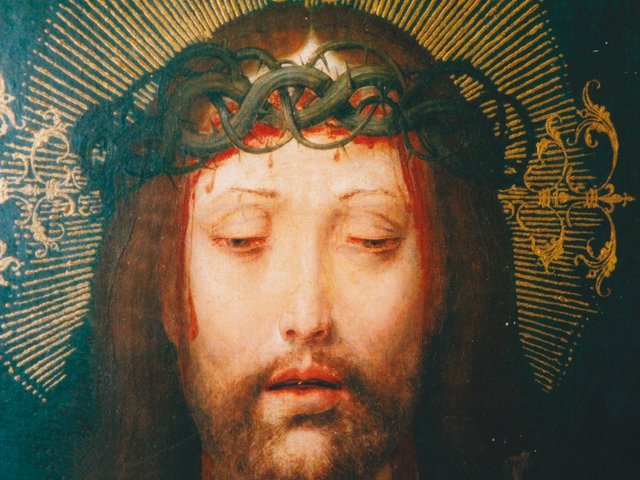

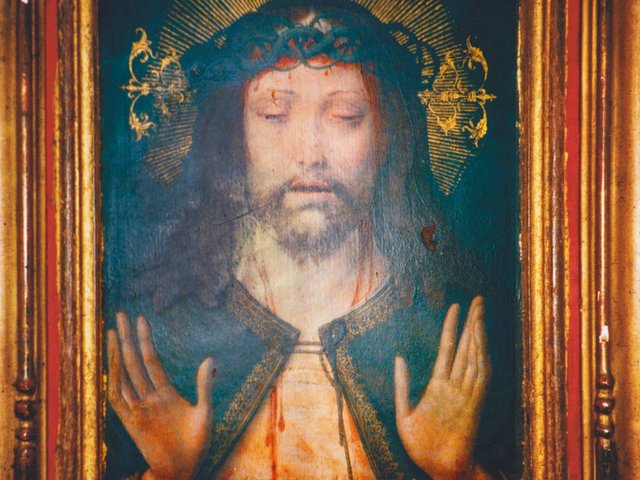

Which European artist painted the mysterious 500-year-old image that became a sacred Ethiopian icon? Last month The Art Newspaper published the first colour photographs of the Kwer’ata Re’esu, which was looted at the battle of Maqdala in 1868. We hoped that these images would make it possible to attribute this historically important painting to a named artist—or at least narrow it down to a geographical area.

The icon was seized from the Ethiopian emperor’s deathbed by Richard Holmes, an agent of the British Museum—but instead of handing it over to the museum he kept it privately. As we revealed, it is now owned by a Coimbra collector, who believed it to be by a Portuguese artist.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu depicts the suffering Christ, blood dripping from his crown of thorns and with his hands raised in blessing. Such images were made by Jan van Eyck in Flanders in the early 15th century, but on stylistic grounds the Kwer’ata Re’esu appears to date from around 1520, a dating which seems fairly universally agreed. Most experts accept this dating, and believe that it was either painted by a Flemish artist or an artist working in Iberia in a Flemish style.

The Art Newspaper has solicited the views of some of the leading European specialists of early 16th-century painting. What comes as a surprise is that the Flemish experts mainly believe the painter was Iberian—and those from Iberia see it as Flemish.

The attribution of the Kwer’ata Re’esu may well end up being of much more than just academic importance. The Portuguese government has restricted its export, stating that it is “possibly Portuguese-Flemish”, perhaps by Lázaro de Andrade or Jorge Afonso. So if purely Flemish, this might change the situation.

Pilar Silva, a former curator at Madrid’s Museo del Prado, believes that the painting is Flemish, rebutting the idea that the artist is either Portuguese or Spanish.

Alberto Velasco, from the University of Lleida in Catalonia, sees the Kwer’ata Re’esu as based on a Flemish model, possibly by Albrecht Bouts (around 1452-1549). He rejects an earlier theory that it may have been painted by the leading Spanish artist Bartolomé Bermejo (around 1440-around 1501).

Plethora of possibilities

Peter van den Brink, the director of Aachen’s Suermondt-Ludwig Museum until last year, suggests that it may be from the circle of Quentin Massys (1466-1530), whose workshop provided altarpieces for Portuguese churches. He proposes that it could be by one of Massys’s Portuguese assistants, such as Eduwart Portugalois (active in the early 1500s).

Didier Martens, the head of art history at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), believes that the artist of the Kwer’ata Re’esu was most likely Portuguese, possibly Frei Carlos (died 1540) or a follower. Carlos, who was born in Flanders, became a monk and worked mainly in Portugal.

Valentine Henderiks, also from the ULB, thinks that the painter was probably Spanish or Portuguese. But the composition seems inspired by a Flemish master, with the frontal depiction of Christ reminiscent of the work of Gerard David (around 1460-1523) and Adriaen Isenbrant (1480s-1551).

Till-Holger Borchert, director of the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum, believes that the artist was not necessarily Flemish. He could well have been Iberian or even German.

With such a wide divergence of views, we are now likely to have to await the eventual re-emergence of the painting, so that it can be studied in detail.