Few artists are as prominent in the UK’s cultural subconscious as Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005). He is on the walls of Tottenham Court Road underground station in mosaic form; he sits menacingly in the forecourt of the British Library in the shape of a sculpture based on William Blake’s Newton (1795); he lolls on a street corner in Edinburgh, as a giant open hand, pointing back down to where he grew up in the dockyard district of Leith. Nevertheless, as the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art celebrates the centenary of arguably Scotland’s most famous 20th-century artistic son, it would appear some reputation enhancement may be in order.

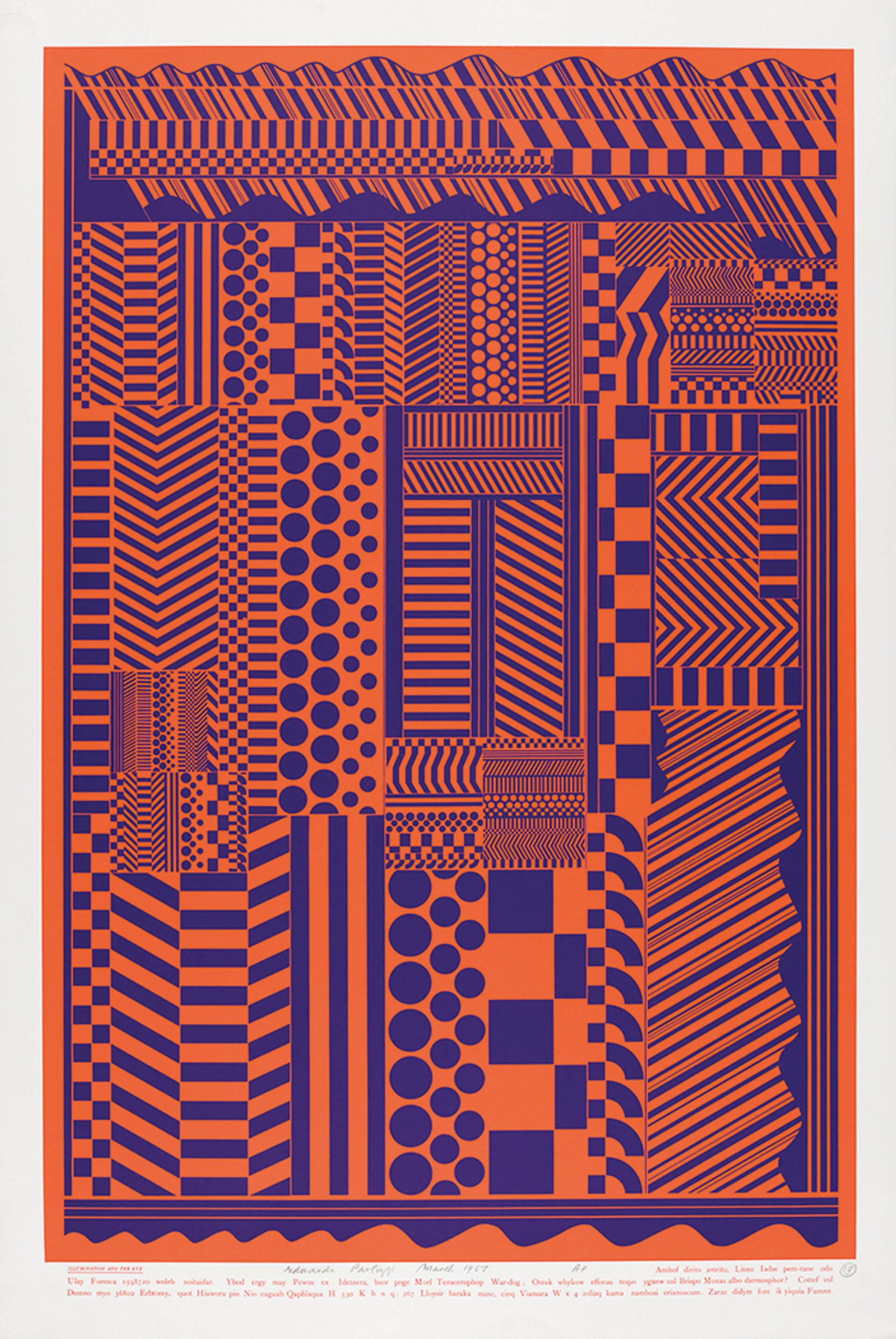

An eye for pattern: Paolozzi’s Illumination and the Eye (1965). A series of different versions of the print are on show © Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation. Licensed by DACS; London 2023

Kerry Watson, the librarian of Modern and contemporary art at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and lead curator of Paolozzi at 100, suggests that the artist’s habit of constant reinvention and amazingly varied techniques may partly be responsible. “Each work is different and each approach is different, and because he had such a long career they are perhaps not instantly recognisable,” she says. “People are familiar with his work without necessarily knowing his name. But that’s not so much the case for us—he is a constant presence in the Modern art gallery. We know there is a fanbase and there’s a real demand for a celebration of his centenary.”

Project Paolozzi

The museum already holds a significant collection of Paolozzi’s work, much of it gifted by the artist himself in the 1990s, and its permanent displays include a reconstruction of Paolozzi’s studio, the mammoth 7m-tall steel figure Vulcan (1999), and a set of ceiling panels originally commissioned for Cleish Castle in Kinross in the early 1970s.

Watson says that part of the exhibition’s purpose is to call attention to the gallery’s ongoing Paolozzi Project—a drive to catalogue and conserve the vast number of items that Paolozzi donated back in 1994, and which is only possible due to a bequest from the art historian Robin Spencer, who died in 2017. “The main activity is to look at parts of the collection that haven’t been accessible,” Watson says. “We want to make it much more accessible to researchers and the general public, and to draw out areas we haven’t focused on previously.”

Paolozzi’s prolific printmaking is of particular interest, Watson says. She points to the first ever showing of a series of versions of the mid-1960s Op art print Illumination and the Eye, “the first time they’ve been out of storage since Paolozzi gifted them”. She adds: “We’re showing the state proof, and seven or eight different colourways of the print,” she adds.

“The way he approaches screen printing is absolutely with a design eye, experimenting with how the colours affect the image,” Watson says. The curator is also keen to illustrate Paolozzi’s keenness for recycling patterns: there is an amazing set of dinner plates the artist produced for Wedgwood a few years later that reworks the print’s design.

Somewhat intriguingly, it is Paolozzi’s early activities with pioneering Pop art collages and rough-hewn figure sculptures that has had somewhat of a recent boost; the Postwar Modern show at London’s Barbican in 2022 gave Paolozzi’s work a central position in its depiction of a society trying to absorb the maiming and disfigurement the Second World War inflicted, as well as his association in 1956 with the forward-looking This Is Tomorrow exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. Watson acknowledges the sheer variety of Paolozzi’s work across the decades, which even includes a bit of acting in the 1956 Free Cinema classic Together, where he plays one of a pair of deaf brothers, along with fellow artist Michael Andrews.

“He had a long career, he was incredibly prolific, and he was just in constant process, which I think you get an idea of from the show,” Watson says. “We have some of those rough figures he was making in the 1950s, with the collage aesthetic he brought from his Bunk series and then applied it to his work in sculpture. Then you move into the 60s and everything becomes chrome-plated and shiny and completely the opposite.”

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Watson says, is the natural home for Paolozzi’s work, even if the man himself moved away from Scotland as an adult. “He’s such an important figure here in Edinburgh and people are basically very fond of him. He was from an Italian family who had an ice cream shop in Leith, a part of the city which has a very distinct sense of community. They are very proud of the fact that such a world famous artist came from here.”

• Paolozzi at 100, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two), Edinburgh, until 21 April