Folk is making a comeback. In music, film, dance—and now, even the visual arts. Stroud, where a handful of grassroots art galleries have opened in recent years, is one of the British epicentres of this growing phenomenon.

Over May Day weekend—traditionally considered the beginning of summer—the small town in Gloucestershire hosted the second instalment of Neo Ancients festival, an eclectic mix of music, Morris dancing, talks, film screenings and exhibitions celebrating the folklore of the British Isles.

The art dealer James Elwes, who organised a show at the local gallery Rattle and Brash, sees Neo Ancients as an opportunity to show artists in a more holistic setting. “Art has always been spiritual and—especially when it folds into other disciplines like music and performance—it can fulfil that almost religious function,” he says. “At Neo Ancients, artists who are big names like Sue [Webster], Jeremy [Deller] and Stanley [Donwood] are doing something completely different to what is expected of them. It’s not Cork Street, it’s not a foundation or a museum or an art fair. It’s mud and soil and paint.”

The Forgotten Garden of Shadows, an exhibition by Matthew Robert Hughes & Emma Thistlethwaite at the Neo Ancients festival in Shroud Photo: © Emlyn Bainbridge

The exhibition, Floralia—which takes its name from the ancient Roman festival that celebrates Flora, the goddess of flowers and fertility—featured new landscape drawings and paintings by Donwood, who has worked with the British band Radiohead creating their album artwork for the past 30 years.

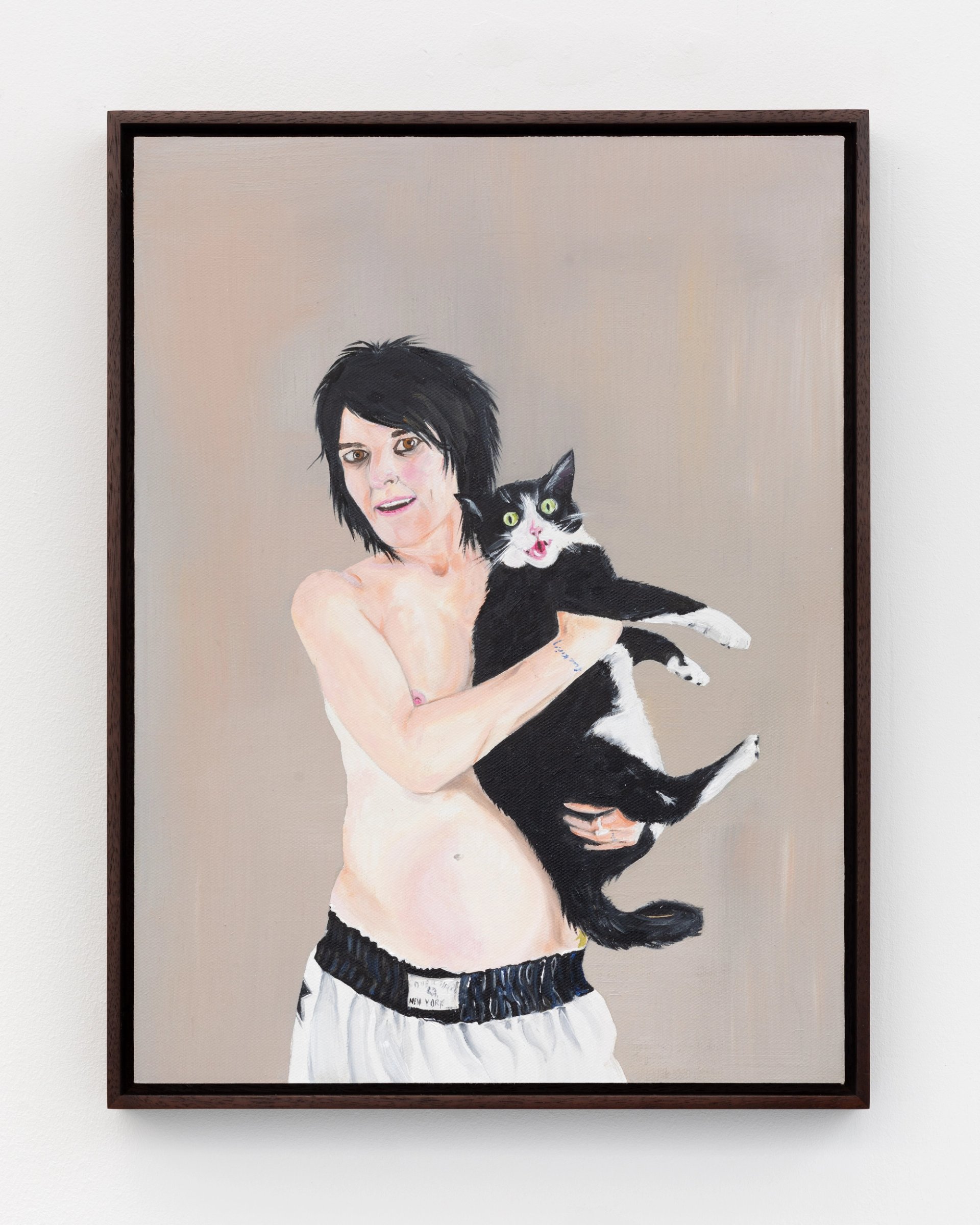

For Webster, the theme of rebirth is particularly poignant. She showed two new self-portraits of her during her pregnancy in her early 50s. The artist, who was part of the YBA generation and made a career making large-scale sculpture with her ex-husband Tim Noble, only started painting just over two years ago.

“I had to reinvent myself after being in a successful collaboration for the best part of 30 years,” Webster told an audience at the festival. “In a way, my self-portraits are still a collaboration because I am collaborating with the new man in my life, my son, who is a small child.” Webster recounts the trauma of trying for a baby and having several miscarriages over several years. “I was determined. I didn’t want to go through life regretting something and so I tried very hard until it worked,” she says. “I also wanted to break that age-old cliché that men like Mick Jagger are allowed to carry on reproducing ad infinitum.”

Sue Webster, The Cat is Out the Bag (2024) Image: courtesy of TIN MAN ART

Elwes thinks there is a growing convergence in the art world between fine art, folk art and spirituality. This is in part a reaction to the over-commercialisation of the art world over the past two decades. “Art has become more pastoral in recent years, which it often does when the socio-political climate gets heavy,” he says. But the dealer believes something more significant is also going on. “I think people, younger collectors in particular, are getting into art less because it is seen as an asset and more because it means something to them. Greater accessibility online and fewer gatekeepers has meant more affordable art sales, as well as more independence for collectors and artists.”

This sentiment chimes with a slowdown in both the museum and commercial gallery sectors, with cash-strapped organisations taking a more considered approach to business. “A lot of galleries are rethinking their model to work more simply,” Elwes says. “Without really intending it we’ve started programming around seasonal festivals and lunar cycles because putting on shows is exhausting. It does feel like things are shifting.”

During another talk at the festival, the London-based artist Ben Edge—who has recently published a book on the oral storytelling traditions of the British Isles—discussed how a younger wave of artists is pushing back against the corporate art world. “There’s a folk art renaissance happening in art schools,” he said. “The younger generation realise we’ve become way too commercial, and they are looking for the hand of the artist, a more personal touch.”

A performance by the American author Tree Carr at the Neo Ancients festival Photo: Anete Lapsa (@nettles_photos)

Barnie Page, who launched pop-up exhibitions in Stroud under the name Sacred Thing in 2021, co-organised a show as part of Neo Ancients together with Legion Projects. Installed in the Chapels of Rest in Stroud Cemetery, the exhibition included floral designs by Emma Thistlethwaite inspired the walled plots and pergolas of real gardens and sculpted figures and architectural remnants created by Matthew Robert Hughes.

Page thinks there are many reasons for the current resurgence of interest in folk—“but at its core is a rejection of the failing capitalist system that has thrown the world into a seemingly never-ending crisis”. Describing the 99% as “neo-peasants”, Page says modern life is becoming more and more feudal. “The lords are the corporations and HNWIs whose wealth is protected tooth-and-nail by the state at the expense of the people and the environment.”

Folk culture, by contrast provides “spiritual escape” through folk stories and songs of resistance, rituals and traditions that “reconnect us to nature’s rhythms and ancient crafts that make us reconsider mass production”, Page says.

While there is a long tradition, particularly in folk music, of using the genre to comment on the politics of the day, there has also been an element of folk culture that has been claimed by nationalists seeking a connection with England’s past. But, as Page puts it, the field is now being “reclaimed by marginalised groups and artists are making exciting innovations”.