When visitors enter the new Fenix museum of migration, they are swept up in a tornado of experience—quite literally.

The museum in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, which opens on 16 May, looks at the politically loaded topic of migration through art. And, appropriately enough, the director Anne Kremers says, visitors step into a spiralling staircase that is also a work of art.

“The first art piece is right in the heart of the building and we call it the Tornado: a double-helix staircase, two staircases hanging into each other,” she says. The two entrances to the Tornado lead to two crossing pathways. “You can change your path, from the ground floor to the first floor and all the way up through the glass roof to the viewing platform. From there, you have a 360-degree view of Rotterdam. What we hope is that you broaden your view on migration.”

The spectacular Tornado, made of stainless steel and two wooden staircases, and designed by Ma Yansong of the Chinese firm MAD Architects, takes up a prominent space on the Rotterdam skyline as though to say: a single, unfriendly view of immigration will not dominate debate in a city that has built wealth and diversity over centuries by opening itself to the world.

Rotterdam is a port city with more than 170 nationalities among its 670,000 people—but it is not just a place for arrivals. It was a main conduit for adventurous Dutch people leaving to find a better life in centuries past: in the years of colonialism, but also after the Second World War, when Rotterdam was destroyed by bombing and battered by the Nazi occupier.

Farewells and arrivals

“There’s history to tell because of the millions of people who boarded ships and set sail to the United States and Canada,” Kremer says, “but also the people who arrived from Cape Verde, from China, from all over the world in Rotterdam. And for Fenix, it is very important to tell stories of farewell, but also arrival.”

The biggest exhibition, called All Directions, will include works around the theme of migration by more than 100 artists. A photography show, The Family of Migrants, will exhibit 200 photographs of people on the move from international archives and newspapers. There will also be a maze built from 2,000 suitcases, together with a book and audio guide sharing the stories of their owners, from the Netherlands to Canada.

Individual works include Red Grooms’s The Bus (1995), made out of fabrics and intended to represent a ride in “the world of imagination”, and Shilpa Gupta’s metal gate, banging against the wall and leaving its own footprint. There is also a large, atrium space called Plein, a 2,000 sq. m covered square open to all, which will be programmed by Rotterdammers and community groups with events such as Chinese New Year celebrations.

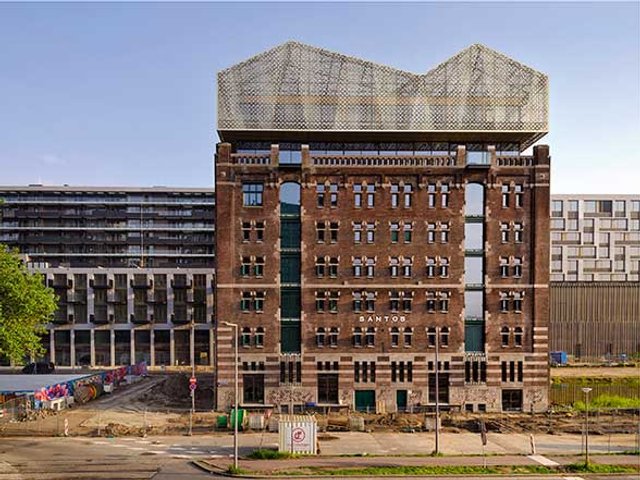

Fenix typifies a community-led sense of artistic reinvention, according to Wim Pijbes, the director of the Droom en Daad art and culture foundation, which purchased the former warehouse in which the museum is housed in 2018.

“Rotterdam in the roaring 1920s was very active; it was the first city where jazz entered, because of the big steamships connecting New York with Europe,” he says. “Rotterdam was the modern town, Amsterdam was the historical town. Rotterdam was really filled with energy, and that whole energy stopped abruptly after the bombing in May 1940, when the city centre was destroyed in a few minutes. Finally, the city has re-found its timbre.”

Pijbes’s own foundation has been working to revitalise prominent but derelict buildings, including the old warehouse that has become Fenix and a former tuberculosis pavilion in a public park. It has also donated prominent sculptures such as Thomas J. Price’s Moments Contained (2023), on display at Rotterdam central station.

Community focus

Community art is an important part of the revival of Rotterdam, says Marjolijn van der Meijden, the senior project leader of art in public space at the Centre for Visual Arts Rotterdam; she believes that a Dutch tradition of giving an art budget to all government building projects, combined with the need to rebuild Rotterdam, actually opened the way for more community initiatives. “They flattened out the whole city centre and rebuilt it, and there were a lot of opportunities for artists and architects to work together,” she says. “And we have a lot of space in Rotterdam.”

Museums contribute, too. Marianne Splint, the director of the Kunsthal Rotterdam, says that recent large commissions from renowned architects for cultural projects are giving the city its character—places for local artists to develop, for local programming and to bring outside influences to the city. “The Depot at the Museumpark [designed by MVRDV] is a recent example, but its origins date back to the 90s, when the Architecture Museum Nieuwe Instituut was built and the Kunsthal Rotterdam was commissioned from architect Rem Koolhaas,” she says. “We want to set the city in motion.”

At a time when the Netherlands has a right-wing government and a national tone of voice on immigration that makes some Dutch people uncomfortable, these places of culture also function as a kind of “soft power”: open spaces for a variety of stories. “It’s not a political statement,” Kremers says, “but we are open. Our goal is to enrich your view of migration.”

It is also a statement about how this trading city was built, according to Said Kasmi, the deputy mayor for culture. “It gives the stories of migration the place they deserve and underlines the power of Rotterdam as a city of migration,” he says. “It’s more than a museum: it is a tribute to the stories that make Rotterdam what it is today.”

The Rotterdam artist Efrat Zehavi, for instance, went around the streets of the city talking to Rotterdammers and creating a series of portraits made in Plasticine. “What she realised is that if you ask someone ‘Where are you going?’, they immediately tell you where they come from,” Kremers says. “And especially in a city like Rotterdam, there are such rich stories. Children’s clay is not hard; it always stays soft. And you can still change it even after ten years, like your identity.”