Norway’s Indigenous artists are gaining profile at home and abroad. A significant milestone came in 2022, when the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was rebranded as the Sámi Pavilion, celebrating pan-Nordic Indigenous artists.

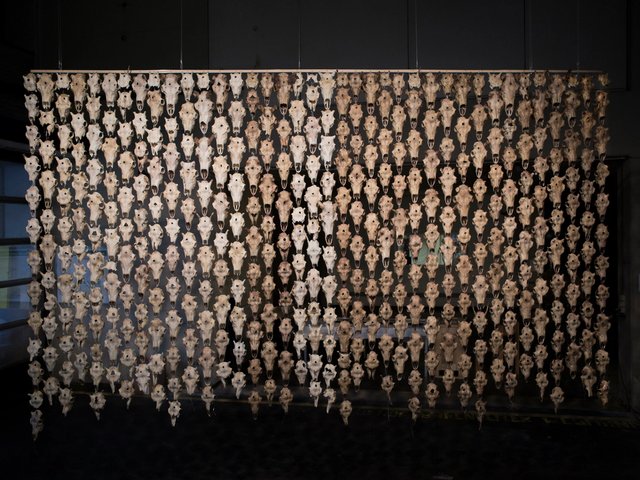

A 50m-high mural by Outi Pieski, a Sámi artist, is set to be a key feature in a new government quarter in Oslo being built after the 2011 far-right terror attack by Anders Behring Breivik. And in March, the Tate announced that Máret Ánne Sara will create a site-specific work for this year’s Hyundai commission at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, opening on 14 October. Born to a reindeer-herding family in Guovdageaidnu in the Norwegian part of Sápmi, she explores global ecological issues through the lens of her experience in the Sámi community.

Yet despite decades of advocacy, no progress has been made in setting up a dedicated Sámi art museum, which has been a demand of the Indigenous community since the 1960s. Thousands of Sámi works of art purchased with Norwegian government funds are still languishing in storage in the basement of a museum of Sámi cultural history in Karasjok, northern Norway, awaiting exhibition in a purpose-built art museum.

The Norwegian parliament last year released a 750-page “truth and reconciliation” report on the country’s treatment of its Indigenous groups, including the Sámi, Kvens and Forest Finns, which acknowledged historical injustices such as forced Christianisation, cultural erasure and boarding schools. The government formally apologised and proposed measures to strengthen Indigenous culture and language, including greater Indigenous representation in national cultural institutions.

Meanwhile, the Northern Norwegian Art Museum recently opened a new branch in Bodø. “I fear this will be used as an excuse to further delay a dedicated Sámi museum,” warns Synnøve Persen, an activist and artist best known for her work Blueprint for a Sámi Flag (1977).

Persen has championed the cause of a dedicated Sámi art museum for decades. She calls for greater engagement from her own community in making a museum happen. “Our artist associations and the Sámi Parliament are asleep at the wheel,” she says. “That’s why no concrete plans are moving forward.”

Katrine Rugeldal, an art historian in the New Sámi Renaissance research programme at the Arctic University Museum of Norway in Tromsø, says that simply integrating Indigenous works into existing institutions is not enough.

“The museum itself is a colonial structure,” Rugeldal explains. “If we establish a Sámi art museum, it should be on Sámi terms, shaped by Sámi knowledge systems and practices.” She questions the very format of such a museum. “Would it be national or pan-Nordic, given that the Sámi people are spread across borders? Should it even be a permanent structure, or might it be nomadic, reflecting traditional Sámi ways of life?”

Last year, Norway’s parliament acquired 13 Indigenous works for its collection through an open call. Liv Bangsund, a member of the Kven people who served on the selection jury, says that few Kven artists applied. “That’s partly because many are only now recognising their Kven heritage,” she explains. “This shows how deeply colonial structures still shape our identity.”

Yet Bangsund remains hopeful. As she organises the third edition of Kväänibiennaali (the Kven people’s biennial) this March in Tromsø, she reflects on the growing momentum. “We’re at the beginning of the Kven people’s artistic spring,” she says.

And while a museum still looks far off, a group of Sámi art organisations is taking action in another form. They are creating a new arts export agency to bring Sámi arts to the world. Fronted by the Indigenous music festival Riddu Riđđu and the Kautokeino-based art collective Dáiddadállu, the agency says it sees “massive” interest for Sámi art outside Norway’s borders and hopes to launch in June.