Enigmatic, intriguing, an anomaly—the adjectives commonly applied to Edward Burra (1905-76) hint at the English painter’s curious position in the landscape of Modern British art. Burra’s unique eye ranged across the louche underbelly of city life, conceived stage and costume designs, and later brought a malevolent energy to empty, brooding landscapes. Burra was the subject of a biography in 2007, a BBC film, and a survey exhibition at Pallant House Gallery in 2011, but a forthcoming retrospective at Tate Britain presents a relatively unknown figure. “People really appreciate his art, and they find it engaging and interesting, but he just gets forgotten about,” says the exhibition’s curator, Thomas Kennedy.

Burra achieved considerable success in his lifetime, participating in the London International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, and briefly joining Paul Nash’s group Unit One. But his reputation has been stymied by his fierce resistance to categorisation, and his withering rebukes for anyone attempting to discuss “Fart”, as he called it. According to his friend, the photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer, he only grudgingly attended his 1973 retrospective at the Tate, walking through “almost without pausing”.

Arranged chronologically, the latest exhibition presents more than 80 paintings and newly discovered archival material spanning the artist’s career from the 1920s to the 1970s. It includes such rarities as Cornish Clay Mines (1970), on loan from a private collection.

Grubby letters

The archive, held by the Tate, offers unprecedented insights, and includes “the hundreds and hundreds of grubby letters which are the principal evidence for Burra’s personal world”, according to his biographer, Jane Stevenson. Letter-

writing was a lifeline for Burra, who was frequently incapacitated by rheumatoid arthritis and a hereditary form of anaemia, which resulted in a lifetime of chronic pain.

Aside from a period at art school in London in the early 1920s, Burra lived all his life in the affluent “Tinkerbell Towne” (as he called it) of Rye, East Sussex. Here he recuperated between bouts of sybaritic adventuring, reliving in paint the jazz clubs of 1920s Paris and 1930s New York—he lived for several months in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance. The paintings are “infused with the rhythmic beat of his music”, Kennedy says, and songs from Burra’s vast record collection (another facet of the largely still uncatalogued archive) will be played in the exhibition.

It was partly through music that Burra accessed memories so vivid that he could dispense with preparatory sketches. “It’s a sight to behold,” Kennedy says. “He did loose line drawings underneath and then painted directly on top. They’re so distinct.”

Watercolours like oils

Aside from early oil paintings and some collages, Burra painted exclusively in watercolour, seated comfortably at a table and working on one small area at a time, to create an effect akin to oils. He made large-scale works by piecing together multiple sheets. The Tate’s own Soldiers at Rye (1941) is composed of three sections, and is typical of the darkening character of the artist’s work during the war years. Burra had been forced to leave his beloved Spain in 1936 at the outbreak of the Civil War, and the savagery of conflict haunted his work thereafter. The show explores this response in unprecedented detail, thanks to his archive.

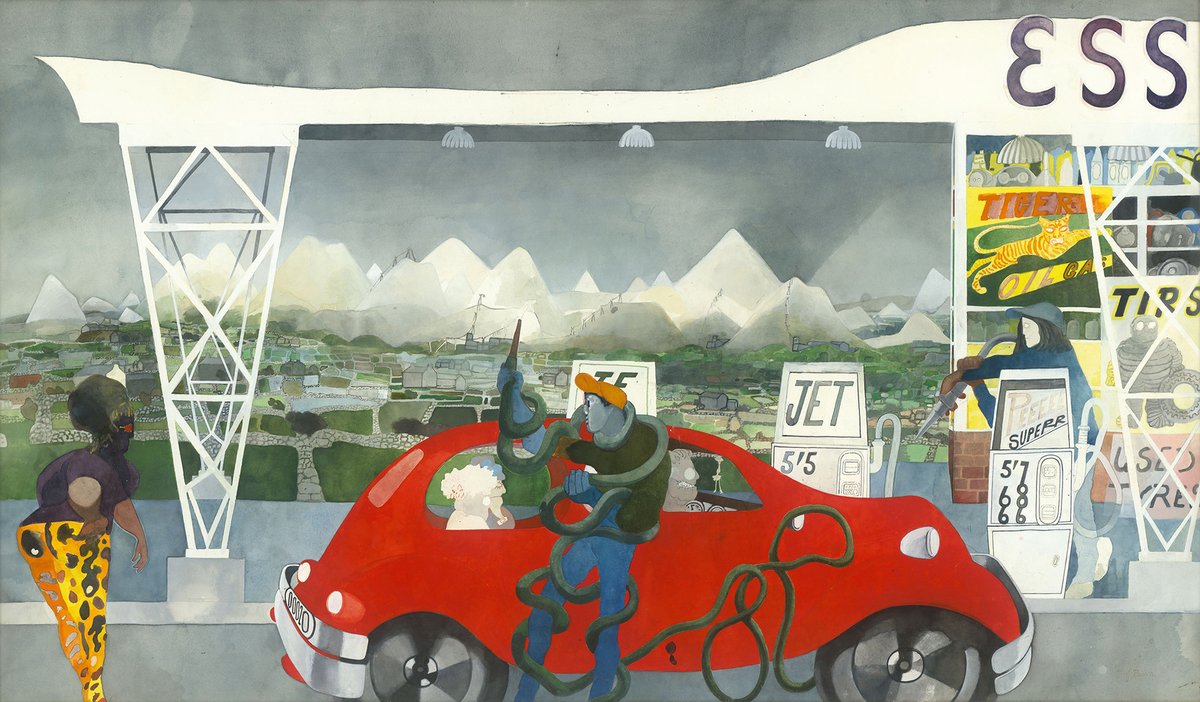

Burra continued to create exuberant stage designs, but as his health further declined, his painting took its cue from driving tours around Britain with his sister. His acid wit did not desert him, and in Cornish Clay Mines a petrol pump dispensing “Peeeee Superr” evinces a banal environmental concern, elevated by the majestic landscape beyond.

In these later paintings, visitors may discern a connection with Ithell Colquhoun, whose retrospective can be viewed on the same ticket at Tate Britain. Though the two artists never knew each other, they shared some common ground as two quasi-Surrealists working outside of the movement—not least their choice of medium, Kennedy points out. “They both pushed the boundaries of watercolour,” he adds. “They experimented in different ways to create startling compositions.”

• Edward Burra, Tate Britain, London, 12 June-19 October