Hilda Trujillo Soto, the adjunct director and later director of the Diego Rivera Anahuacalli and Frida Kahlo museums in Mexico City from 2002 to 2020, has accused the trust that oversees both museums of mismanagement and negligence in an extensive blog post published on 2 April.

Trujillo Soto’s most explosive claim is that in 2009 and 2013, the trustees turned a blind eye when presented with evidence that works belonging to the museum devoted to Kahlo, known as the Casa Azul, may have been stolen and sold to private collectors in the US.

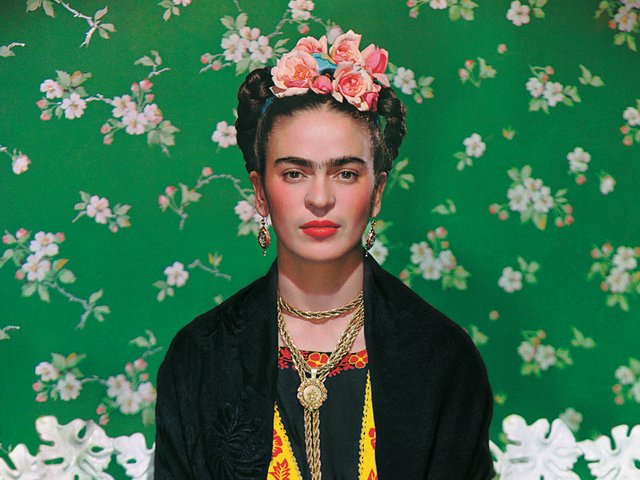

The works of Rivera (1886-1957) and Kahlo (1907-54) hold pride of place in the Mexican imagination and are accorded special protection under Mexican law. As “artistic monuments of the nation” they can be bought and sold within Mexico but may only leave the country temporarily, unless the Institute of Fine Arts and Literature (INBAL) issues a special export permit.

In response to Trujillo Soto’s allegations, the INBAL issued a statement on 3 April clarifying that it had not issued such permits for “permanent exports” of works by Rivera or Kahlo.

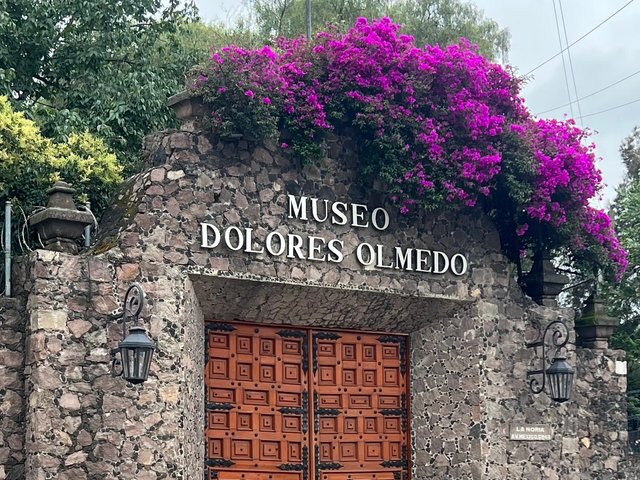

In addition to their works’ special legal status, in 1955 Rivera placed the collections of the Museo Anahuacalli and the Casa Azul in a trust managed by Mexico’s central bank, the Bank of Mexico (Banxico). Rivera charged the trust (Fideicomiso de los Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo) with running the museums and maintaining their collections “for the people of Mexico”, and for that purpose granted the trust copyright over his oeuvre as well as those works by Kahlo found in the Casa Azul. When Rivera died, his longtime patron, Dolores Olmedo, gained control of the trust’s governing body (Comité Técnico) and served as the director of both museums until her death in 2002. Her son, Carlos Phillips Olmedo, succeeded her as director general of the museums. That same year, the trust hired Trujillo Soto as adjunct director; she was elevated to director in 2009.

“It has been some time since I’ve known that several works by Frida Kahlo have disappeared from the Casa Azul,” says Helga Prignitz-Poda, a German art historian who is the foremost specialist on Kahlo and co-editor of her catalogue raisonné. “I would like to thank [Trujillo Soto] for bringing this fact to light.” Linda Downs, the former executive director of the College Art Association (CAA) and a specialist on Rivera, also confirmed to The Art Newspaper that in 2014 she became aware of missing notebooks and sketches by Rivera from the Casa Azul archive. Representatives for the Casa Azul did not respond to requests for comment on missing works from the collection and archive. In interviews with The Art Newspaper, Trujillo Soto reaffirmed the details of her post regarding the missing works.

In a public response to Trujillo Soto on 3 April, the trust released a statement that reads in part: “The person making these accusations today never filed a formal complaint during their professional association with the trust. On the contrary, their contract was terminated after irregularities were detected in their administration and for having benefited third parties with the assets under their care.”

‘Administrative irregularities’

In October 2020 Phillips Olmedo and the trustees informed Trujillo Soto that her role as director was being made redundant and issued a press release naming her as an adviser for special projects. Trujillo Soto sued the trust in February 2021, alleging she had ceased to receive her salary. According to her lawyer, María del Rocío Pecina Castro, the dispute is now before the Seventh Chamber of the Federal Tribunal of Conciliation and Arbitration of Mexico. “If benefiting third parties means hiring qualified specialists and not trying to do everything in-house, then yes, that’s what I do,” Trujillo Soto tells The Art Newspaper. Asked about the alleged irregularities in her administration, she says: “Let them prove it.”

At the heart of Trujillo Soto’s allegations of negligence and mismanagement

at the trust and the museums are two separate episodes suggesting works may have been stolen from the Casa Azul. The first involves the diary kept by Kahlo during the last ten years of her life. It had been on display in the Casa Azul until 2003, when, according to Trujillo Soto, Phillips Olmedo removed it from its case and placed it in a safe in a bathroom at the Casa Azul. By 2009 the museum had acquired new equipment that necessitated moving the old safe. Trujillo Soto hired a locksmith to open the safe, whose contents were then inventoried by the staff. While comparing the diary to its facsimile, the staff realised it was missing six folios.

Documents included in Trujillo Soto’s post and reviewed by The Art Newspaper state that she immediately informed Banxico’s trustee on the Comité Técnico, José Luis Pérez Arredondo, who retired from Banxico last year as head of internal audits. Pérez Arredondo did not respond to repeated requests for comment. According to Trujillo Soto, Phillips Olmedo, then director general, was himself present in the Casa Azul when staff realised there were pages missing from the diary. Phillips Olmedo did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s repeated requests for comment.

In 2018 an internal restructuring placed the Comité Técnico under the supervision of Banxico’s new Office of Financial Education and Cultural Development, headed by Jessica Serrano Bandala. According to Trujillo Soto, the incident related to the diary’s missing folios was communicated to Serrano Bandala. Serrano Bandala did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s repeated requests for comment. Banxico’s current trustee on the Comité Técnico, Luis Rodrigo Saldaña Arellano, also did not respond to repeated requests for comment. The whereabouts of the six diary folios remain unknown.

The second episode outlined in Trujillo Soto’s post dates from 2013. In 2011-12, Phillips Olmedo, then director general, hired outside researchers to compare Rivera’s notarised inventory from 1957 of objects in both the Anahuacalli and the Casa Azul with the museums’ collections. According to Trujillo Soto, when the researchers delivered their findings to Phillips Olmedo and José Luis Pérez Arredondo, evidence suggested that multiple works from the 1957 inventory were missing, with auction records suggesting they had been sold in the US. Neither Pérez Arredondo nor Phillips Olmedo responded to The Art Newspaper’s repeated requests for comment on this internal investigation. According to Trujillo Soto, Serrano Bandala also learned of the results of the investigation sometime between 2018 and 2020. Serrano Bandala and Saldaña Arellano did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s repeated requests for comment about these missing objects in the trust’s care.

Multiple missing works

Among the missing objects by Kahlo listed in Rivera’s 1957 inventory are the 1954 painting Frida in Flames; the 1952 painting Congress of Peoples for Peace; American Liberty, an undated work on paper; the 1932 drawing The Sun Peeked Through the Window; four undated pencil-on-paper works: Portrait of Irene Bohus, Drawing for Brewery, Fantasy of a Stove and Part Object; the 1935 drawing My Bedpan Doesn’t Love Me Anymore; the 1936 drawing Study for “My Grandparents, My Parents and Me”; and a print and eight proofs of the 1932 lithograph The Abortion, one of which is inscribed “19a” and “últimas pruebas” (final proofs).

According to Trujillo Soto, these were likely sold through the New York-based gallery Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art, which specialises in Mexican and Latin American Modern art. On 4 April the gallery’s website was inaccessible for several hours. Since then it has come back online and its page for Kahlo lists her dates but no other information or inventory. The site has previously listed at least two of the works allegedly missing from the Casa Azul: Frida in Flames (under the title "Self-Portrait Inside a Sunflower") and American Liberty. Martin did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s repeated requests for comment.

Sofía Lacayo Remy, a former employee of the gallery, tells The Art Newspaper that between 1996 and 2001 she handled several works on paper by Kahlo, including prints of The Abortion. According to Lacayo Remy, the gallery did not use Rivera’s 1957 inventory for provenance research during those years.

Trujillo Soto’s claims come at a time when the trust is finalising loan agreements for the planned exhibition Frida: The Making of an Icon at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, due to open on 18 January 2026, then travelling to Tate Modern in London. In response to an inquiry about Trujillo Soto’s allegations, a spokesperson for the MFAH says: “We are not in a position to have any knowledge of the activities of previous administrations of the Casa Azul. We have been impressed by the professionalism and commitment of the current administration.” A spokesperson for Tate says: “It wouldn’t be for Tate to comment on another organisation.”