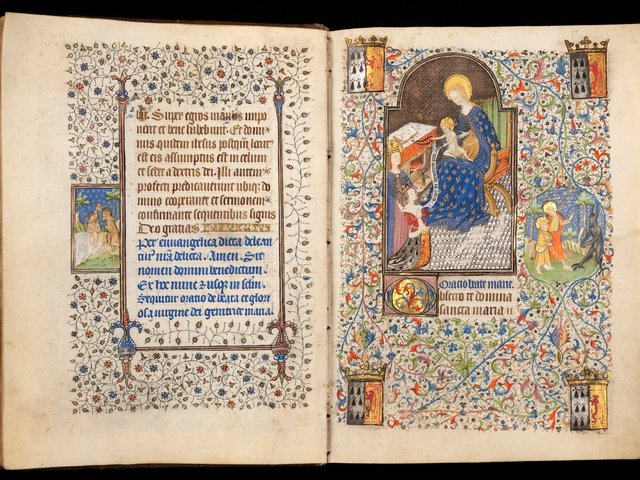

A little dog sniffing a plate on the white table cloth, unnoticed by the Duc de Berry, presiding over a magnificent New Year feast. The frozen breath of a peasant trudging through February snow. A grape picker bending over during the September harvest, exposing his backside in front of the many-turreted Château de Saumur. This is the world of the Très Riches Heures, arguably the greatest and most valuable of all medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Commissioned by the Duc de Berry, the enormously wealthy brother of King Charles V of France, this exquisite Book of Hours was begun by the Limbourg brothers, a trio of Netherlandish miniature painters, in around 1411. The Duc and the Limbourgs died in 1416. The manuscript was completed by other wealthy patrons and talented artists 70 years later and contains 131 full-page illuminations. Now, in a vanishingly rare opportunity, the general public has been invited to step into this world.

Until October, visitors to a special exhibition at the Condé Museum in the Château de Chantilly, 55km north of Paris, will be able to view as independent works the 12 monthly calendar pages of the Très Riches Heures, on which much of the fame of this 15th-century prayer book rests. Its importance and influence are contextualised by an exceptional display of some 100 medieval manuscripts, sculptures and paintings loaned from museums and libraries around the world.

The Très Riches Heures have been jealously immured in the Château de Chantilly since 1856, when they were acquired by the renowned French art collector, the Duke d’Aumale. The conditions of his bequest forbid the display of the manuscript outside Chantilly.

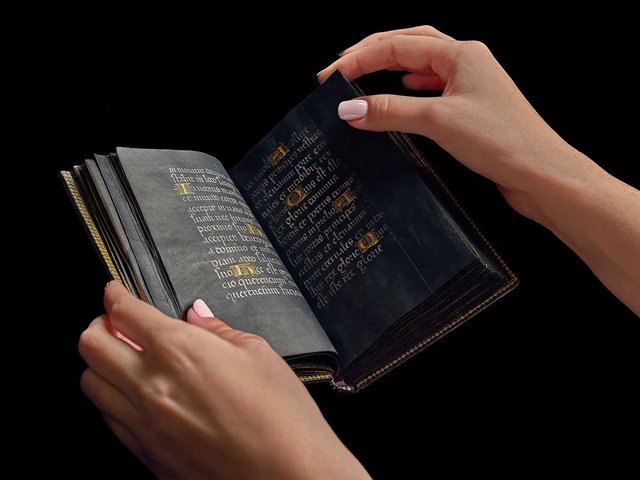

Moreover, owing to the fragility and preciousness of the illuminations, the Très Riches Heures have not been shown to the public for decades. But the centuries-old binding and some of the paint surfaces have been subject to a painstaking conservation project, allowing the famous full-page calendar paintings to be temporarily detached and put on view.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to display the calendar before everything is rebound and it disappears again,” says Mathieu Deldicque, the director of the Condé Museum of the Château de Chantilly, who has been working on this exhibition for 12 years.

According to Deldicque, Books of Hours—collections of prayers to be said at each canonical hour of the day—enjoyed a unique status in late 14th- and early 15th-century France, with wealthy patrons such as the “greedy but pious” Duc de Berry. “A Book of Hours is a book that you can personalise more than others,” says Deldicque, explaining how illuminated manuscripts became a laboratory for artistic innovation in the late Middle Ages.

The finest details of of the newly conserved manuscript were originally rendered with brushes consisting of a single squirrel hair

Copyright Château de Chantilly

The Duc owned no fewer than 18 Books of Hours. Six of the most sumptuous were commissioned by the Duc himself, the most sumptuous of all being the Très Riches Heures, the finest details of which were rendered with brushes consisting of a single squirrel hair.

“There is lapis lazuli and gold everywhere,” says Deldicque. “At the time, lapis was more expensive than gold; it had to come from Afghanistan. That was why they were called the Très Riches Heures.”

But, as the renowned scholar Christopher de Hamel, author of the 2016 book, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, explains, the Très Riches Heures are so much more than a luxury object. “The staggering originality of the design and composition is overwhelming,” he says. “The full-page calendar miniatures were the first ever made. It marks the very first moment when the Renaissance touched northern Europe.

“Religious art suddenly becomes human: these are real scenes, real people, recognisable places. There is landscape and perspective as never before, there is humour and pathos, reflections and weather,” adds De Hamel, referring to how the Très Riches Heures contain what are thought to be the first snow and night scenes in northern European art.

Given all this, it is hardly surprising that the Très Riches Heures are, according to Google’s AI Overview “widely considered the most famous illuminated manuscript in the world”. And yet, because of the restrictions surrounding its display, this is a world masterpiece whose fame has been almost entirely based on photographic reproductions.

But now, for just a few weeks, it is possible to get up close and admire the real thing.

- Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berr, the Condé Museum in the Château de Chantilly, France, until 5 October