For years, Vija Celmins has created detailed paintings and drawings of spiderwebs, expansive night skies and rippling ocean waves. “Though she rarely offers verbal explanations, the clarity and intensity of her vision over the years are unmistakable,” says Theodora Vischer, the chief curator of the Fondation Beyeler, which is holding a comprehensive solo show of Celmins’s work this summer. Exploring 60 years of the artist’s creative output, the exhibition underscores Celmins’s enduring drive to push the limitations of a flat surface.

Born in Riga, Latvia, in 1938, Celmins spent her early years moving between Latvia, Germany and a refugee camp as the Second World War displaced her family. In 1948, they emigrated to the US, settling in Indianapolis. Celmins moved to Los Angeles for art school in 1962, finding herself in the city at a time when vibrant West Coast colours and Pop Art were replacing the popular Abstract Expressionist style. Celmins’s work, however, took a different direction, as she opted for more muted colours and an overall slower pace. Her initial subjects were everyday objects, such as a lamp and a heater.

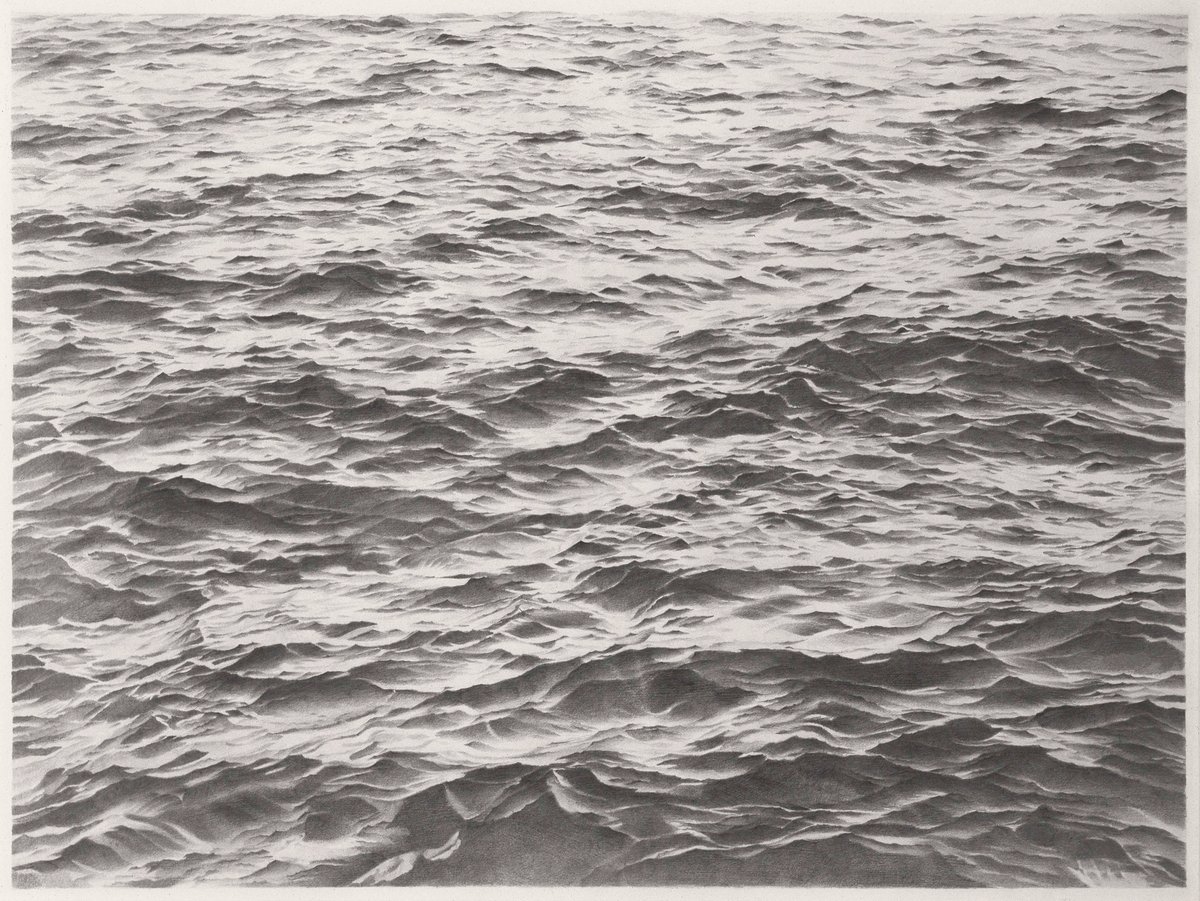

Vija Celmins says a preferred medium is pencil, because it is “dense yet precise” Laurie Lambrecht

From painting to pencil

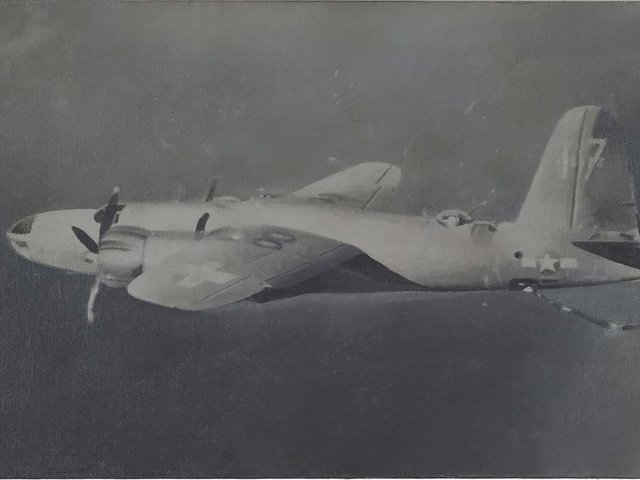

“I pretty much painted everything in my studio and started making some three-dimensional objects and painting them,” Celmins tells The Art Newspaper. She soon became interested in photographs of war and began incorporating this imagery from magazines and books in her work. Homing in on details like planes gliding seemingly weightless through the air, Celmins depicted her subjects detached from violence, as if quieting the noise of war.

In 1968 Celmins’s medium shifted. “I dropped paint,” she says, “because I was not satisfied with it. I fell for the pencil—maybe so I could explore its ability to be dense yet precise. I got stuck there for about 18 years. Later, I picked up some charcoal and found it best with using erasers to draw.”

The two-dimensional plane is a complicated space… so much illusionVija Celmins

The materials suited Celmins’s palette of choice, which consists primarily of shades of grey. She portrayed clouds, waves and deserts—imagery she saw while living near the ocean and later spending time in New Mexico—focusing on the surfaces and meticulously rendering the details. “I basically got tired of the background and foreground of an object and decided to tackle the image together with the ground, laying it carefully so all space is accounted for by the image,” she says.

These subjects became Celmins’s main focus for decades, as did expanses of the cosmos and the night sky, her interest piqued by the images of the moon and deep space from US and Soviet space missions in the mid-1960s.

“It wasn’t just the natural world that captivated her—it was also the elusive, often intangible nature of these spaces,” says Vischer. Celmins puts it more simply: “I like the night sky and the cosmos.”

Infinite possibilities

In depicting something infinite on a two-dimensional surface, Celmins “invites the viewer into a deeper, almost meditative space, while always remaining anchored to the flatness of the page,” says Vischer. “It’s this ‘double reality’ that continues to drive her practice: the challenge of capturing the unfathomable within the strict limits of the pictorial plane.”

The Beyeler exhibition spans these developments and explorations of the infinite and includes a small selection of sculptures as well, a discipline that offered the artist another opportunity to consider spatial depth. “The two-dimensional plane is a complicated space… so much illusion,” Celmins says. “I turned to three-dimensional every now and then, just because I liked to make objects and was inspired by Pop Art, Jasper Johns, and maybe even Claes Oldenburg.”

In curating the exhibition, the Beyeler worked closely with Celmins. “It was hard to install work that was made 60 years ago,” the artist says. “We tried our best with the most dedicated and attentive curator.”

For Vischer, the experience was a reminder of what defines Celmins’s practice. “She remains a striking and uncompromising figure, entirely immersed in her work,” Vischer says. “Revisiting the works, especially those from the mid-1960s onwards, served as a powerful reminder of their enduring presence. They demand to be seen in person, experienced directly, in their full physical and spatial reality.”

• Vija Celmins, Fondation Beyeler, until 21 September