The Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut is out to prove that the US’s histories of whaling and capitalism go hand in hand.

The new exhibition Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact contains 19th-century photographs, blubber hooks, ship models, captain’s logbooks, the massive jawbone of a sperm whale, a jar of blue whale foetuses and all manner of products made from whale oil. Coming from the museum’s permanent collection and gathered all together for the first time, these objects collectively paint a picture of “an industry that lit America’s lamps and greased its machines for over a century”. On the back wall, a giant scratchboard mural of a sperm whale by the contemporary artist Jos Sances watches over the exhibition.

The “monstrousness” of the show comes not just from the size of the sperm whales that were hunted nearly to extinction. “These are monstrous tools for a monstrous task with monstrous ramifications,” says Debra Schmidt Bach, the Mystic Seaport Museum’s director of exhibitions, pointing to whaling as an early example of “Americans’ history with addiction to oil”.

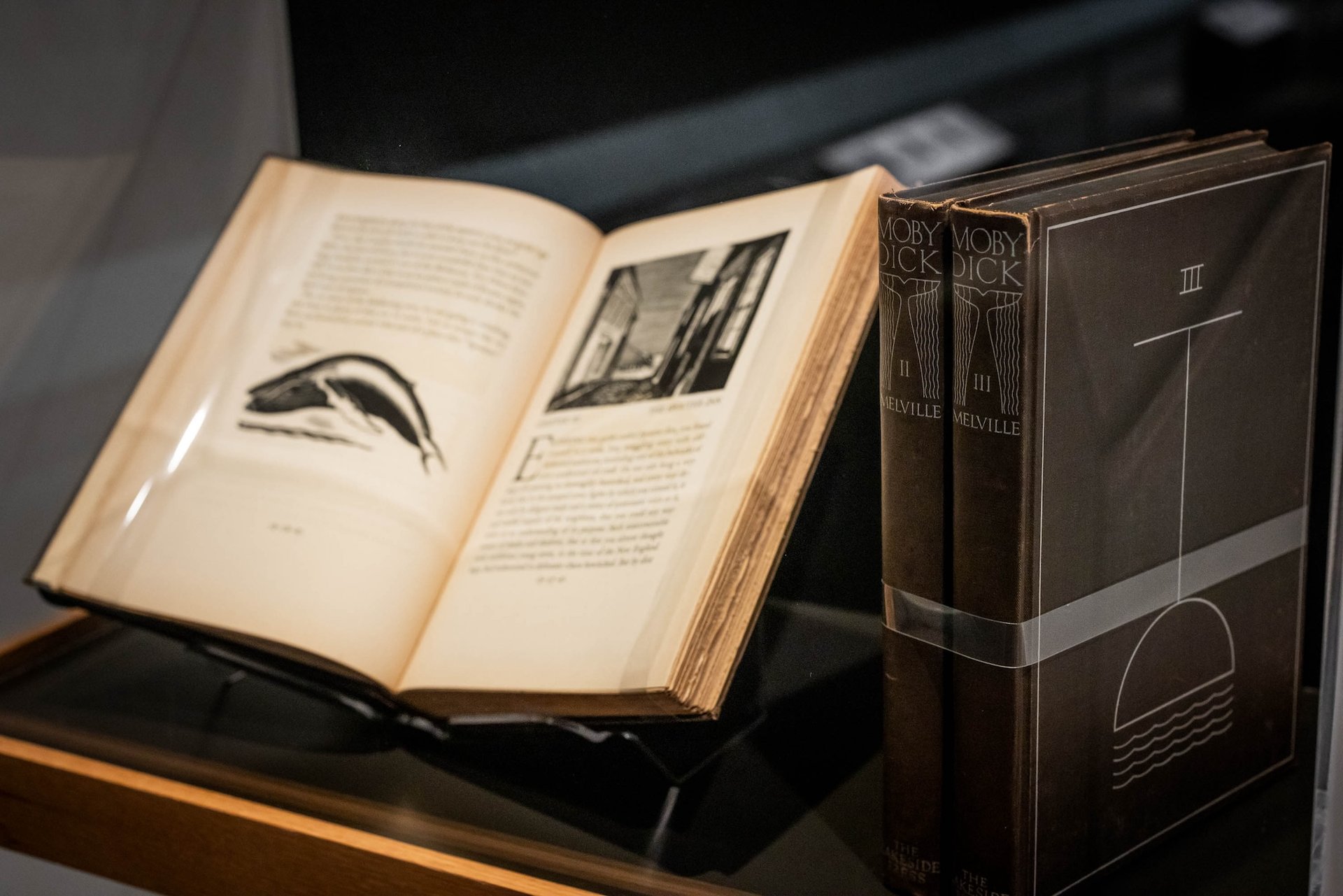

Copy of a 1930 three-volume edition of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick; Or, The Whale (1851) Courtesy the Mystic Seaport Museum, Connecticut

Of course, there is a long history of cultures worldwide killing various types of whales for meat and blubber, but it was the US’s whaling industry that chose to focus on the species with the most “oil” that could be extracted from them. A sperm whale’s blubber was valuable, but the real prize came from the animal’s large and distinctive head full of a waxy substance called spermaceti. While the whale is still alive, the spermaceti helps with buoyancy and echolocation. When killed and processed by humans, spermaceti was used to make things like candles, oil for lamps and machine lubricants. (Ambergris, a digestive material found only in sperm whales, was popularly used in perfumes.)

Whaling reached its height in the US in tandem with the Industrial Revolution. Whale oil not only greased the actual wheels of industry, the whaling vessel itself became a “floating oil-processing factory”. Because a dead whale would inevitably rot by the time the ship returned from a whaling mission, which could drag on for years—not to mention the size and heft the whale carcass—the crew was tasked with both killing the beast and boiling its blubber in 200-gallon iron cauldrons onboard. Whalers collected thousands of gallons of whale oil and spermaceti in giant barrels, storing them below deck.

The captains of whaling ships liked to show off how many animals their men had slaughtered. Captain Fred H. Smith, for example, kept samples of oil from individual whales hunted between 1875 and 1878 in labelled vials organised neatly inside a special wooden box. This box, with its 26 sealed vials of whale oil, is on view as part of the Monstrous exhibition.

Examples of scrimshaw Courtesy the Mystic Seaport Museum, Connecticut

The white whale in the room

No whaling exhibition is complete without mention of Moby-Dick, and Herman Melville’s 1851 tome looms large over the Mystic Seaport Museum’s show—with quotes from the book reproduced on the walls and copies of an illustrated three-volume version from 1930 proudly displayed. In fact, the artist Rockwell Kent’s hand-drawn illustrations for this edition of the book are echoed in Sances’s 51ft-long mural, Or, The Whale (2019-20), aptly named after Melville’s subtitle. Inside Sances’s whale, the artist has etched scenes from the history of capitalism in the US.

Fittingly, the Melville Society hosts its international conference this week in the neighboring town of Groton. And later this summer, the Mystic Seaport Museum hosts its 40th annual marathon reading of Moby-Dick aboard the Charles W. Morgan, a historic whaling vessel on its campus.

Although sailors are not often known for their artistic talents, some of the most beautiful objects on display in Monstrous are examples of scrimshaw—designs, scenes and even portraits intricately engraved into whale teeth by crewmembers in their free time onboard. Many of these depict scenes of whale hunting with a patriotic motif.

“These are trophies of their exploits,” says Michael Dyer, the show’s curator, “capturing the dynamics of the hunt and their personal experiences.” While the talents of individual crewmembers vary widely, as Dyer says: “Human beings, left to their own devices, will create art.”

- Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact, Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut, until 16 February 2026