Three ancient bronze gladiator helmets so well preserved that you could “put them on today” are taking centre stage at an exhibition opening at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds this week. The show, titled Gladiators: Heroes of the Colosseum is the 16th rendition of a blockbuster touring exhibition dedicated to the famous arena fighters, which so far has drawn in more than a million visitors worldwide.

The exhibition, the first to be held in new temporary exhibition galleries at the museum, has been organised in collaboration with the Colosseum in Rome and features objects dating back more than 2,000 years. The focus for the Leeds iteration—the first in the UK—is on arms and armour. However, also on display will be everyday objects such as cutlery, surgical equipment and souvenirs acquired during visits to gladiatorial fights. Immersive and interactive installations will, meanwhile, drop visitors into the heart of the action and give a sense of the nuances of gladiatorial life.

The arms and armour are on loan from the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, and were all originally discovered in Pompeii, which was once home to gladiator barracks and an amphitheatre where battles would be staged. Among these exhibits are finely decorated greaves for leg protection, as well as the tip of a trident.

The three helmets, meanwhile, offer unique insights into the different roles gladiators could play, and the categorisations that governed their appearance and who they fought.

One piece was worn by a thraex gladiator, a representative of the ancient Thracians, who were from southeastern Europe and eventually subjugated by the Romans. The head of a griffin, which often appeared at Thracian tombs as a guardian, dominates the helmet’s comb or ridge, an important feature that strengthens the object. Another helmet was designed for a murmillo, a heavily armoured gladiator named after a type of saltwater fish. This heritage is reflected in the decoration, too—the comb resembling a fin, below which is a crown featuring depictions of figures including a victorious personification of Rome and “barbarian” captives.

Both of these objects, due to their ornamentation, would likely have been used in processions, explains Matthew Wood, the Royal Armouries Museum’s exhibitions project manager, where “the organiser of the games would emerge at the front, sometimes on a chariot” and trumpets would be played.

The helmet of a murmillo, a type of gladiator named after a saltwater fish

Royal Armouries and Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

Features on the third helmet suggest it may have been designed for use in battle. “It’s a helmet of a controretiarius, and what’s amazing about that is that you can see the thinking behind it,” Wood continues. “Controretiarius were designed to chase the retiarius, who used a net, so this helmet is designed to have as few features as possible. So if you threw a net over it, there's fewer places for it to catch and snag.”

We can consider all of these artefacts “true works of art,” says the director of the Colosseum Rosella Rea. She adds: “the helmets [today] lack the thick and colourful plumage that was an additional element to increase the stature and visibility of the gladiator.” Wood says they are in such good condition that ”you could put them on today and... [for example] the visors would still work—though we haven't and nor would we.”

A complex tale

The helmets nod to another key aspect of the show: the complex place gladiators held in society and their relationship to the public.

“[Many gladiators] were the lowest of the low in society: slaves, prisoners. And they wore helmets to almost dehumanise them,” Wood says. While others, Rea adds, were “liberti, who were freed slaves, and also free-born men, including knights, senators and even an emperor, Commodus, who performed in the arena of the Colosseum armed as a secutor. The free men, called auctorati, were dedicated to [being gladiators] for mere profit and desire of fame, giving up civil rights [in return].”

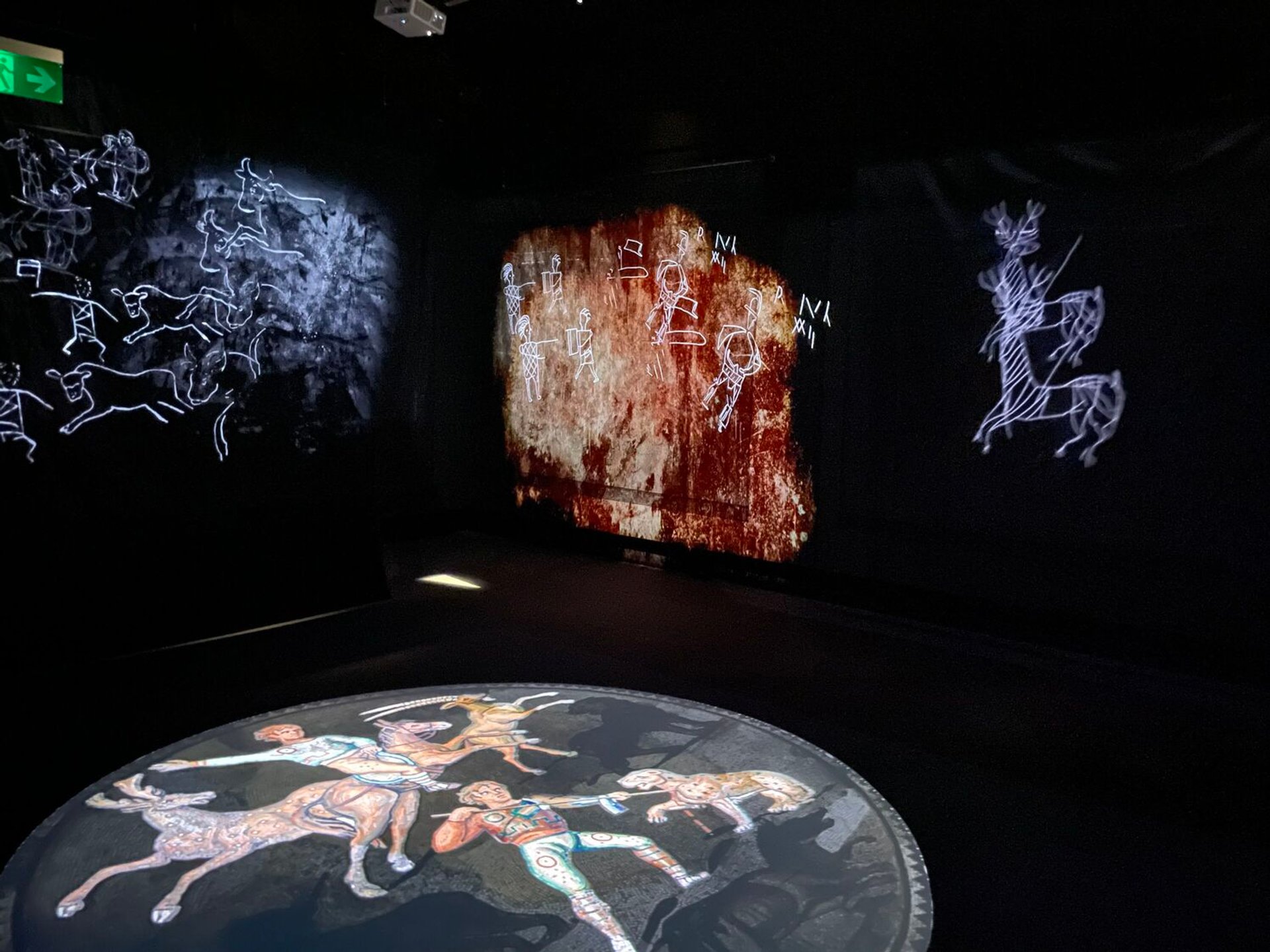

Despite their generally low status, gladiators were the subject of fascination among the Roman people. In Leeds, an immersive room will feature images of graffiti found in the Colosseum as well as some of the “elaborate mosaics that would have been in the the richest of Roman villas”. Also on display will be souvenirs taken home from days out at battle. Among these are “little statues depicting a gladiator or a couple during a fight and, especially, lamps with combat scenes, they were not only decorative, but also useful,” Rea says

The exhibition features immersive rooms featuring recreations of ancient Rome graffiti and more

Contemporanea Progetti

While these ancient warriors were primarily symbols of the Roman masculine ideal of virtus (courage, virtue and manliness), women also occasionally fought in the arena—a topic that the Royal Armouries Museum is organising a lecture on during the run of the show.

A changing image

In a society where gladiators are synonymous with blockbuster films—such as Ridley Scott’s Gladiator franchise—and television shows, the mission of Heroes of the Colosseum is to “bring back the real gladiators,” Wood says. The exhibition sets out to help us “understand and appreciate them, and the people they were, rather than the cultural reference they've become for us,” Wood says.

In this vein, the show will also feature exhibits bringing to life gladiators' calibrated diet—which was largely devoid of meat but filled with beans, barley potage and fresh vegetables—and their rigorous training routines. These are factors, Rea says, that makes them comparable to “modern sportsmen”.

Meanwhile, one particular object powerfully underlines the gladiators’ humanity: a funerary stone of a gladiator called Urbicus. Such stones tend to be detailed in their descriptions, and so offer a vital window onto the lives of the deceased.

“Urbicus was 22,” Wood says. “He'd reached the rank of sort of head gladiator. We know he had a wife and children, and we also know from that account as well that he'd spared another gladiator and was subsequently stabbed in the back by them. So we think the the stone was probably erected by his wife and also his fans. There's a picture of a dog, so we assume we had one.”

It is an object that “really brings it back,” Wood says. “This idea that gladiators weren't just faceless figures, they were people.”

- Gladiators Heroes of the Colosseum, Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, 28 June-2 November