An archaeologist has studied broken statues of Queen Hatshepsut—one of the few women to rule as an Egyptian pharaoh, 4,000 years ago—and found that they were not attacked during the persecution of her memory, as previously believed, but ritually “deactivated”. The statues were excavated during the 1920s at the ancient site of Deir el-Bahri in Luxor, 500km south of Cairo.

“Because these statues were discovered in highly fragmentary condition, it was assumed that they must have been violently broken up by Thutmose III (her nephew and successor), perhaps due to his animosity towards Hatshepsut,” says Jun Yi Wong from the University of Toronto and author of the research paper, published in the journal Antiquity.

Queen Hatshepsut initially ruled as regent for her young nephew, Tuthmose III, but as the years passed, she had herself crowned as co-pharaoh. After her death, the ancient Egyptians hacked out her images and names from her monuments, leading some archaeologists to suggest Thutmose wanted to rewrite history. Other experts have argued that Thutmose was motivated by hatred.

Now, Wong has investigated Hatshepsut’s broken statues by searching through archival material from the 1920s excavations, including unpublished documents. This enabled him to locate where archaeologists originally uncovered the statue fragments and the conditions in which they were found. Significantly, Wong discovered that the statues sustained extra damage long after Thutmose’s reign, when they were broken up and reused as raw material, complicating the picture. When he discounted this later damage, it provided new insight into how Thutmose had apparently actually treated Hatshepsut’s statues.

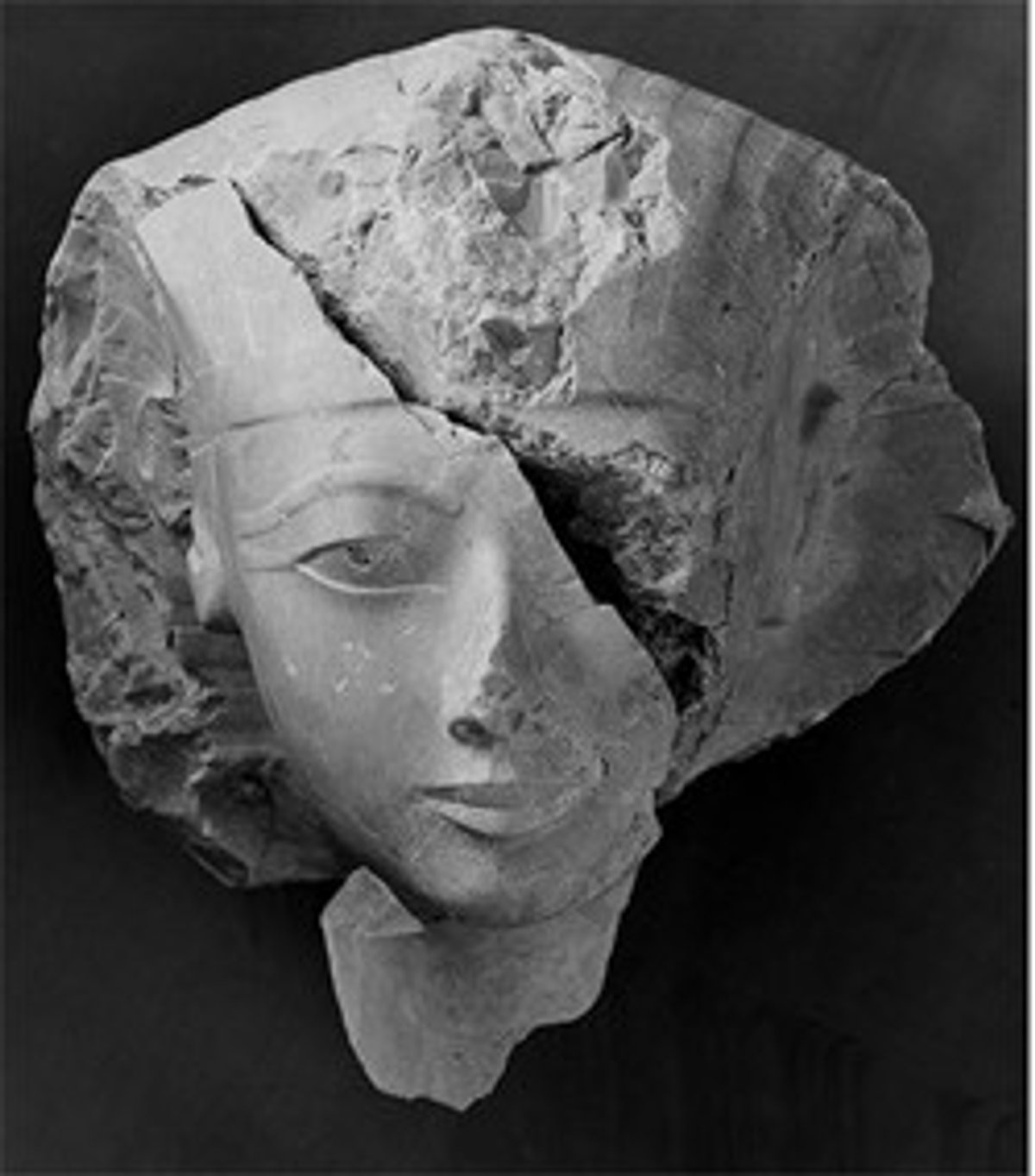

Fragments from an indurated limestone statue of Hatshepsut (approximately life size, photographed by Harry Burton in 1929

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art Archives. Antiquity Publications Ltd, Jun Yi Wong

“Once you take away all this later damage, you find that the destruction caused by Thutmose III was limited and very methodical—the statues were broken across specific weak points, in line with what is often described as the ‘deactivation’ of Egyptian statues,” Wong says. “This is quite surprising, because rather than being driven by hatred and animosity (as was previously assumed), the destruction of Hatshepsut's statues seems to have been motivated by pragmatic and ritualistic reasons.”

An ancient ritual

The ancient Egyptians regarded royal statues as powerful entities and performed a ritual on them called “the Opening of the Mouth” to bring them to life. When they wanted to dispose of a statue—perhaps simply to make space in a temple, for example—they first had to “deactivate” it, usually by breaking the statue across its neck, waist, and knees. This neutralised the statue’s power. Archaeologists have discovered hundreds of statues from across Egyptian history buried at Karnak Temple in Luxor, with the vast majority “deactivated” in this manner, Wong explains, but these kings were not subjected to any hostilities after their death.

The head from an Osiride statue of Queen Hatshepsut, partially restored with plaster

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Antiquity Publications Ltd, Jun Yi Wong

Although Hatshepsut certainly still suffered a programme of persecution, Wong’s findings reveal that this was a far more nuanced phenomenon than previously believed.

“The research process was a lot of fun—a bit like trying to solve an ancient whodunnit, and it is very satisfying to have landed on some tangible findings at the end (which is not always a given),” Wong says. “I suppose that most people think archaeology in Egypt is all about finding tombs and mummies (which is exciting, obviously). But you can also learn so much just by re-examining existing data from a different approach and perspective.”