The long-running Norval Morrisseau art fraud investigation reached a turning point this week when James White, a central figure accused of orchestrating the distribution of fake Indigenous art, pleaded guilty in Ontario Superior Court.

According to Inspector Jason Rybak of the Thunder Bay police department, who was a lead investigator in the case that he began in 2019 after an initial 2011 case led by federal authorities failed to produce any convictions, White was a “ringleader” in a multi-layered forgery operation.

Inside the 'biggest art fraud in history': what the alleged mass forgery tells us about the market for First Nations art in Canada

The investigation Rybak led with a team from the Thunder Bay Police Service and supported by the Ontario Provincial Police, dubbed Project Totton, uncovered three large forgery rings operating in northern and southern Ontario. White was identified as a central figure in one of these rings, involved in the manufacturing, marketing and sale of hundreds of fake Morrisseaus, some of which sold for tens of thousands of dollars.

Rybak tells The Art Newspaper that White pleaded guilty to two charges, “creating forged documents and possession and trafficking of forged art works”. While White admitted to trafficking 502 works of forged art, Rybak says, “We suspect there are more.” The other six counts of fraud White was initially charged with were dropped. The same eight charges he faced are still standing against two of his alleged accomplices, Paul Bremner and Jeffrey Cowan.

The investigation has already led to multiple arrests, including those of David Voss and Gary Lamont, who pleaded guilty earlier this year and both received five-year prison sentences. White’s sentencing was set for 7 August.

According to Cory Dingle, the executive director of the Estate of Norval Morrisseau, White’s plea is notable because of his “active role in both the production and the legal shielding of fraudulent artworks, as well as his deep influence over the network that distributed them across Canada and internationally”.

“White was often the key intervenor in civil court cases, aggressively defending the authenticity of the fake artworks and helping prolong the deception,” Dingle says. “This is more than just another guilty plea, it’s a vindication for all those who fought to preserve Norval’s legacy, often in the face of public doubt, legal threats and personal attacks.”

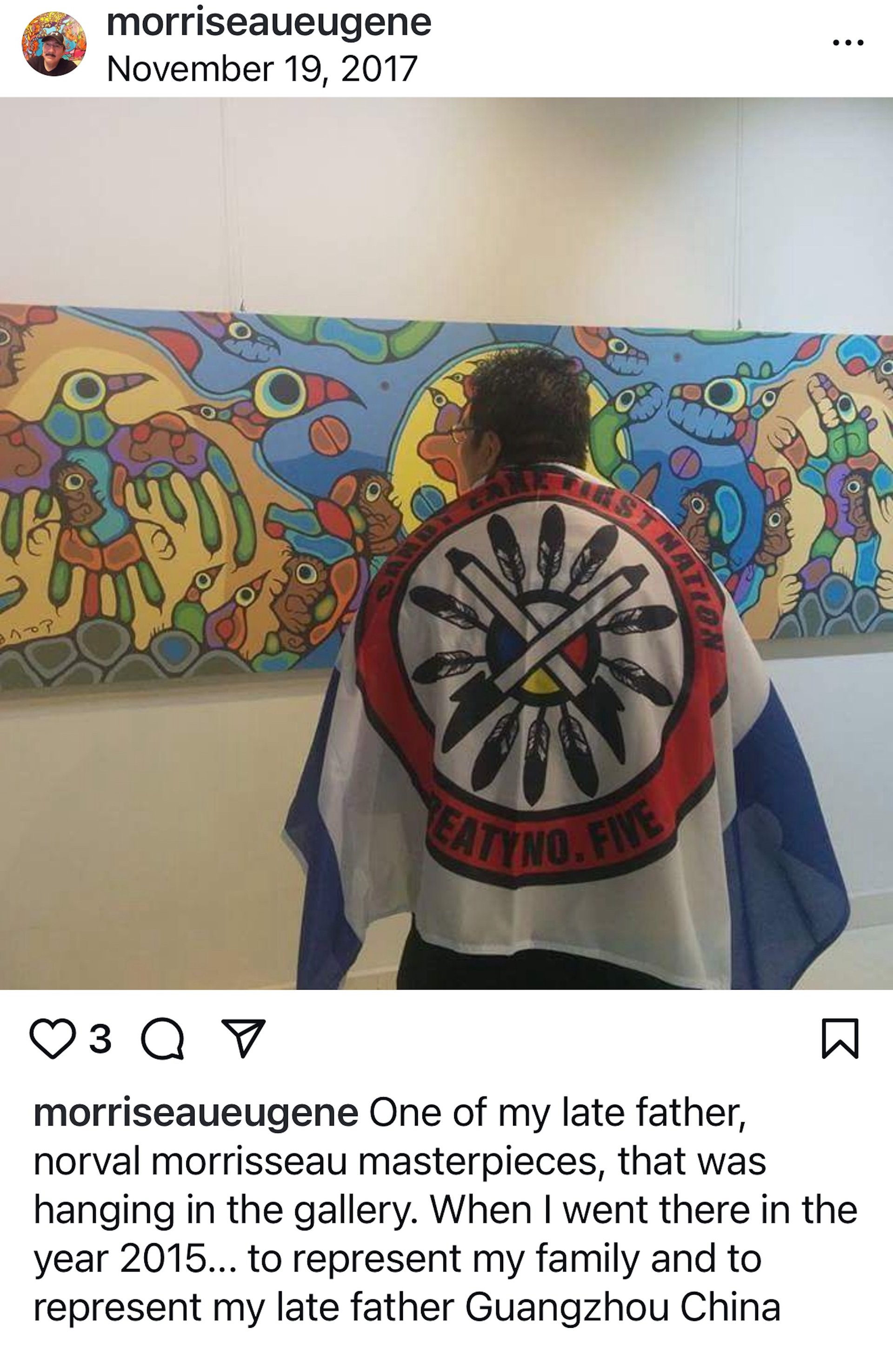

An Instagram screenshot provided by Inspector Inspector Jason Rybak that shows Eugene Morrisseau, Norval Morrisseau's son, standing in front of an allegedly fake painting at an exhibition in China in 2015 Courtesy Thunder Bay Police Service

According to Rybak, his investigation determined that there were three components to the labyrinthine forgery networks. Beginning in 1995, Voss produced between 4,500 and 6,000 forgeries imitating Morrisseau’s mid- to late-1970s style. A second ring was initiated in Thunder Bay by Lamont in the early 2000s, where he produced around 150 to 200 fakes exploiting Indigenous artists including Morrisseau’s nephew Benji Morrisseau. White began dealing in the fake Morrisseau works from both rings in 2008, bringingin Bremner to produce fake certificates of authenticity and relentlessly pursuing those who said the works were fake in court and on social media.

Rybak estimates there are still thousands of fake Morrisseau works at large in Europe and in China. Ultimately, he says, the case took so long to crack because of a perfect storm of racism, homophobia, weak art fraud legislation in Canada and the dawn of social media, where the defendants used every means possible to discredit Morrisseau whenever he took issue with the forgeries, using his alcoholism, bisexuality and nomadic lifestyle against him. (Morrisseau died in 2007.)

Rybak adds: “This investigation would never have taken so long if Morrisseau were not Indigenous.”