In 1920, a young Armenian painter named Vosdanig Manuk Adoian emigrated to the US, fleeing from the Armenian genocide. After four years living with relatives in Massachusetts, he moved to New York City and changed his name to Arshile Gorky in honour of the celebrated Russian poet Maxim Gorky.

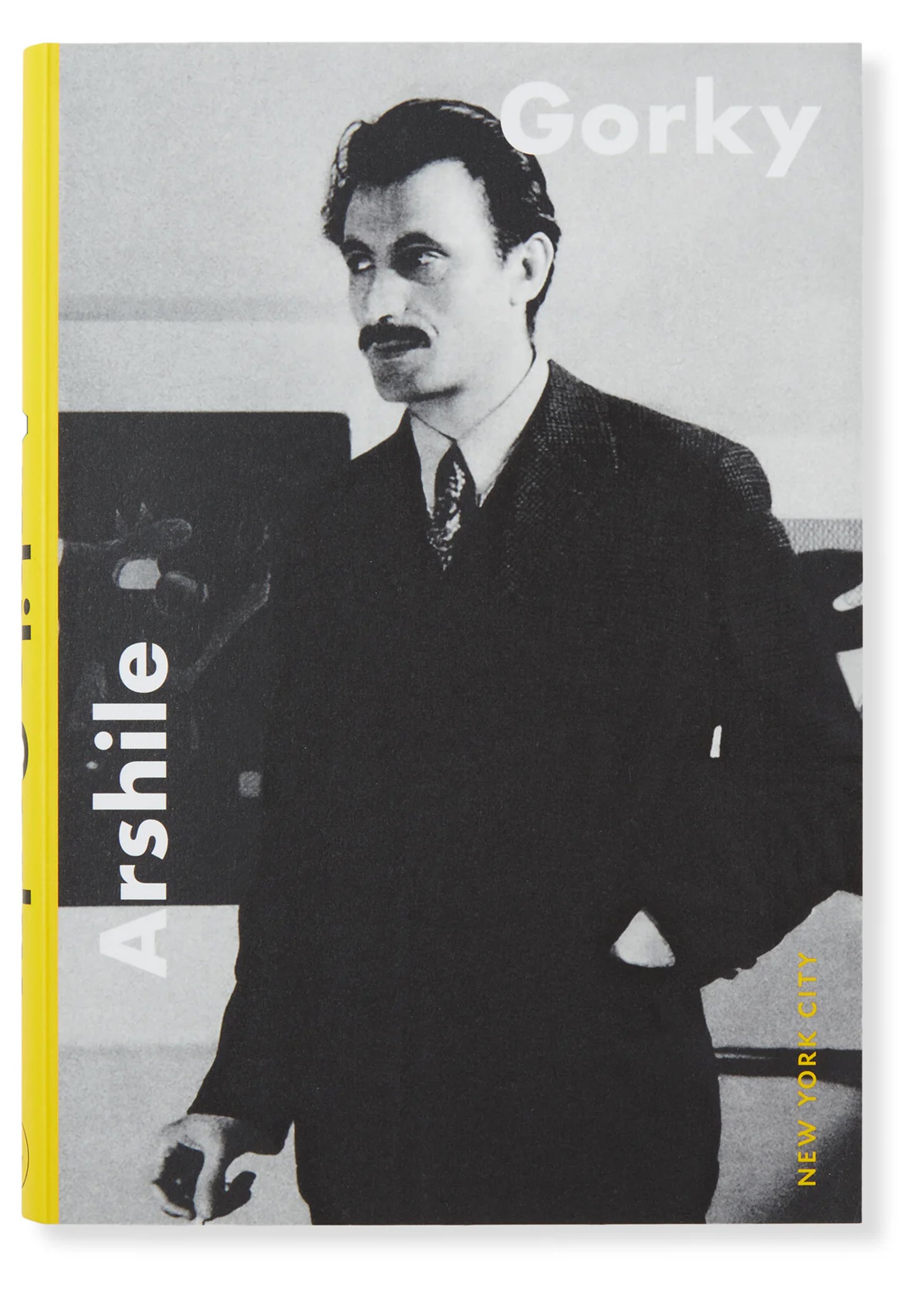

A new publication titled Arshile Gorky: New York City, edited by Ben Eastham, examines Gorky’s artistic evolution against the backdrop of New York as a Modernist mecca, straddling Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. In the book, writers and art historians explore Gorky’s Manhattan years, including Adam Gopnik who, in the essay “Gorky Again”, reflects on the relationship of the artist’s paintings to time and place. Here, he turns our focus to an important double portrait and Gorky’s experience as an Armenian immigrant to the US.

Extract from ‘Gorky Again’ in Arshile Gorky: New York City

What Arshile Gorky and the other great immigrant observers of America had in common is that each pursued a passion in the modern sense, making art against the grain of commerce, while each underwent a passion in the mythical Greek sense—had some moment of struggle or pain that resolved in art, and, often, in the closest thing artists get to immortality: a place in the collective memory. In the artist’s last interview [1948], he again describes himself as Russian, but also as an “early American”, who, according to his interviewer, “dislikes being called a foreigner and says he is more like one of the first settlers because he can appreciate the advantages of being in America to a far greater extent than those who were born here by ‘lucky accident’”.

With Gorky we sense a classic immigrant’s plight: a desire to restore and recuperate the recipes and precise tastes and qualities of a lost, more savoury and less homogenised past, while making it live within the scale and ambition of American reality. Scale alone becomes a vital form of assimilation: do it big and you do it American. To do “Poussin over entirely from nature” was Cézanne’s cry; to do the artisanal, puzzling, irregular Old-World particularism—a world wrought, as Gorky itemised, from the shape of apricots and baker’s bread—over in a landscape of grand generalisations and unlimited horizons, that was the dream that [Willem] de Kooning and Gorky shared.

And so, we keep coming back to Gorky’s prime, begetting picture, a masterpiece of the American immigrant experience, which is to say of the American experience: The Artist and His Mother (around 1926-36). Taken from a formal photograph, remade over more than a decade, [it is] the foundation of his art. We see boy and mother and know that she will die, unthinkably, of starvation in his arms, as part of the [Armenian] genocide, and never see her son again. The image sits so sharply within our consciousness, no matter how often we return to it, because it offers something not illustrative but iconic, part of now-vanishing stories of loss redeemed by possibility. From starvation and persecution and the wistful enforced formality of the Old World, comes, after a long voyage, energy and hope—and with the hope, a residual longing for the older world, and a need to picture all that happened between the departure and the painting. Gorky’s kind lives as a series of passionate pilgrimages made by improbable arrivals and painters who, however necessarily absurd in their effect at moments, struggled against unimaginable hardship to realise their images.

Gorky's last written words before his painfully premeditated suicide [he took his own life in 1948]—“good-bye my ’loveds,” in one version—were a cry of the heart of a suffering man who loved his daughters, as well as a literary reference to a phrase [the Russian poet and playwright Alexander] Pushkin is reported to have written before he died following a duel. The curse of history and the hope of renewal, old and new drawn together in pain. All artists die in a duel, perhaps the duel of talent against the world. We honour them not by placing them back in history, but by reminding ourselves that what we call history is just what they did, which was everything they could.

• Arshile Gorky: New York City, Ben Eastham (editor) and various contributors incl. Adam Gopnik, Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 244pp, £32 (pb)