“I may be on the plains of Troy, or in Odysseus’s palace, but I’m using my own environment to feel my way into those stories,” says the artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins from his home in the Monmouthshire hills, southeast Wales, where he recently finished illustrating a special edition of Emily Wilson’s acclaimed translation of Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey, which is being published by the Folio Society.

Hicks-Jenkins is known for illustrations that respond subtly but acutely to retellings of ancient stories, from fairytales to Beowulf. In 2020 he won the V&A Book Illustration Award for Hansel & Gretel: A Nightmare in Eight Scenes, based on the puppet opera he devised with the British poet laureate Simon Armitage.

“For me, text is everything,” Hicks-Jenkins says, emphasising the unique significance of Wilson’s Homer, not just as a translation by a woman, but by “an academic with a poetic heart”.

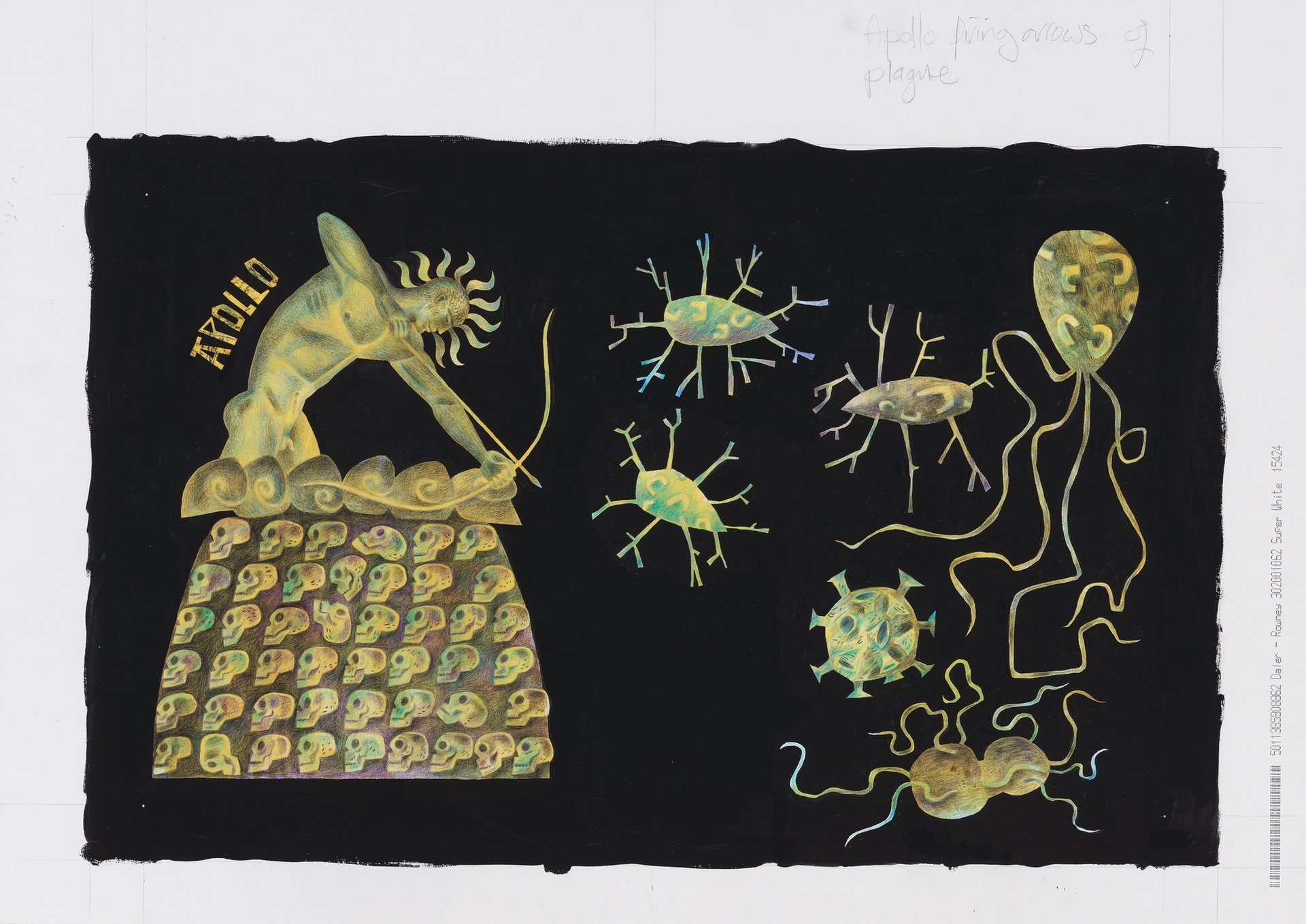

Hicks-Jenkins’s Apollo Firing Arrows, illustrating a key event from Homer’s The Iliad Courtesy of the artist

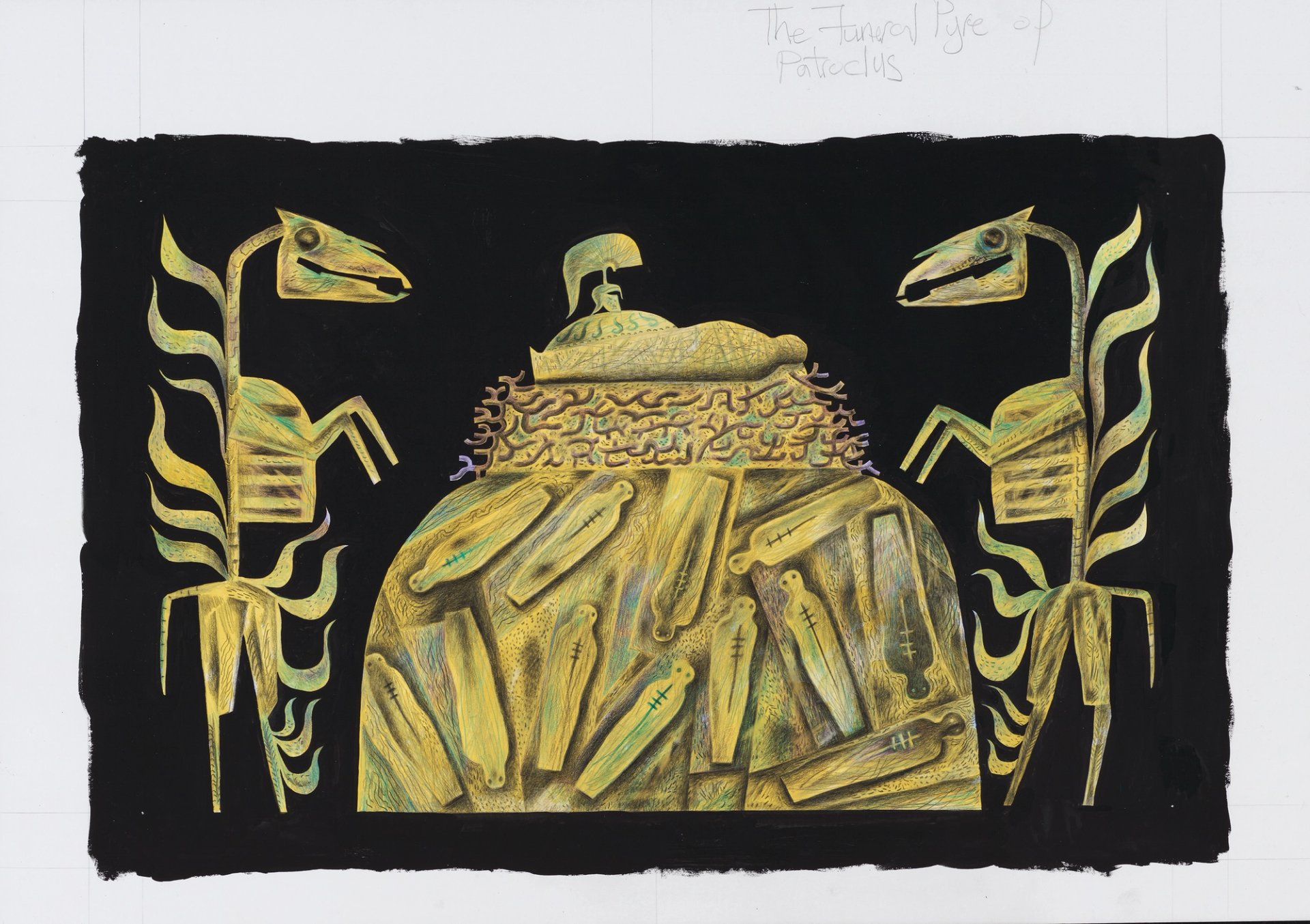

“I don’t want to distract the reader, so the images are intended to not interrupt too much,” he says. “They’re breaths within the text, so the illustrations are in the same palette throughout so that you’re not having to adjust your eye to a cacophony of colour, and then back to black-and-white text.”

If words are Hicks-Jenkins’s foundation stones, technical restrictions can also shape the character of his illustrations. When the Folio Society published a limited edition of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf in 2023, “they wanted to use letterpress, and that means only hard-edged images—you can’t have tonalities because of the metal plates,” Hicks-Jenkins says.

A limited edition of Beowulf translated by Seamus Heaney and illustrated by Hicks-Jenkins Courtesy of the artist

The epic poem’s origins as a story told by firelight unlocked a distinctive linear aesthetic. “I decided that I would think about Beowulf being told through the medium of shadow puppetry, with images that would flicker and change with the firelight,” Hicks-Jenkins says. Since Anglo-Saxon shadow puppetry did not exist, he looked to Chinese and Javanese traditions, imbuing filigree figures with the flavour of Anglo-Saxon enamel work.

In contrast, for Homer, Hicks-Jenkins has used gouache worked over with pencil to create a painterly style that references Archaic Greek art, but does not slavishly reproduce it.

The artist’s surroundings—the landscape of the Monmouthshire-Herefordshire border, and his studio—are his most important resources. “My studio is full of folk art and toys and books from my childhood, and they’re touchstones to creativity,” he says. “I can look at one of those toy theatres that I played with when I was a child, and wham, I’m right into that whole world of making new worlds, peopling theatres, peopling sets, peopling stories.”

Clive Hicks-Jenkins’s Funeral Pyre of Patroclus from Homer’s The Iliad Courtesy of the artist

The language of the theatre is ingrained. Hicks-Jenkins began his career as a dancer, becoming a choreographer and then a director and designer. It is an unforgiving environment, which eventually he left, to emerge as an artist around the turn of the millennium.

“Being a choreographer taught me so much about the processes of how audiences look at and interpret what they see,” he says. “The frame is common to the stage and a painting. The shape of a book, too, is a frame. The frame is where all my various endeavours overlap. I’ve spent a lifetime making things to be viewed through frames.”

Finding ways to illustrate Homer’s blood-soaked epics demanded the sum of Hicks-Jenkins’s experience. “The descriptions are hideous, the violence is unendurable and vivid, and [Wilson] doesn’t pull back from that,” he says. “You have to find a way of showing the impossible. An artist can do that because we have all sorts of means at our disposal, including abstraction. You can take something that would be awful if you had to stare at the detailed horror of it, and reduce it to something that is more schematic—not to make it acceptable, but to enable people to look rather than turn away.”

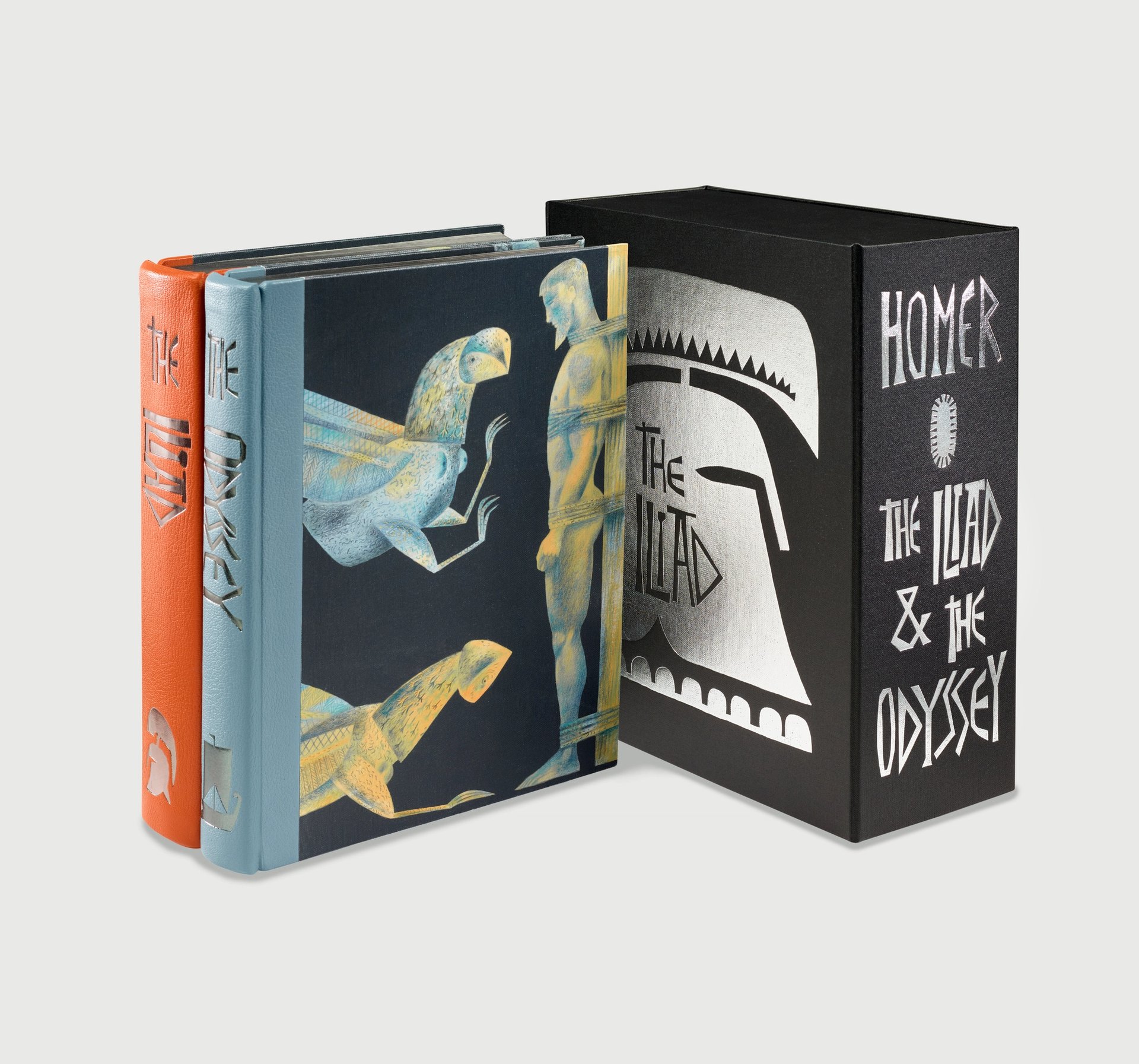

Homer's The Iliad and The Odyssey, translated by Emily Wilson and published by the Folio Society

Whether illustrating books, painting landscapes or still-lifes, or designing ceramics and textiles, “I consider it all to be the same thing,” Hicks-Jenkins says. “It’s the same environment of creativity.” Narrative is at the heart of his practice—hence his affinity with books, which is given something close to free rein at the Folio Society, with its almost boundless budgets for ultra-special editions. Founded in 1947, it has an illustrious roster of artist-illustrators that includes Paula Rego, Elisabeth Frink, Eileen Cooper and Quentin Blake.

Honouring classic texts underscores the value of their reinterpretation by artists. “When I was doing The Iliad, I was thinking a lot about Trump’s America and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine,” Hicks-Jenkins says. “We see it all again today: thugs and potentates who think that they own the world and sort of do, too often. So everything is interpretation.”

• The Iliad and The Odyssey, Homer, translation Emily Wilson, illustrations Clive Hicks-Jenkins, Folio Society, published 12 August