Iraq’s growing economy and improving security situation—in spite of the escalating conflict between Israel and neighbouring Iran—are renewing optimism in the country’s art scene. Artists who fled Iraq during its years of violence are returning to work on projects, and curators—mostly from the Arab region—are beginning to tour the country and its art scenes.

“The Tishreen protests were a turning point,” says Hella Mewis, a co-founder of the Baghdad art platform Tarkib, referring to the anti-corruption demonstrations of 2019. “Especially for young women, who went out in the street among everyone else. Because Covid came straight after, we are only now seeing the effects of that revolution, but it is a generational shift.”

Mewis launched Tarkib ten years ago with a group of artists that included Zaid Saad and Akram Assam, now her co-directors. It has become a key platform for critical art, offering both workshops and internationally minded exhibitions, such as the public-art programme Baghdad Walk, initiated in collaboration with Olafur Eliasson’s Institute for Spatial Experiments, and their annual contemporary art festival.

Visitors to Tarkib, a contemporary art platform that was launched ten years ago © Image courtesy of Tarkib

Artists are also chafing at the conservativism of the art scene, which remains dominated by painting. Last year, the Zurich-based artist Wathiq Al Ameri set up Babil Performance Art to focus on performance work, inviting 16 artists to a farm he bought in the Babylon region to work and show together for ten days. Some of the international artists stayed away last year because of the fighting between Iran and Israel. Though the situation is the same this year, he hopes the invitees will make it. And for the local artists, the opportunity to work in performance was a huge success.

“Iraqis are thirsty for new art,” he says. “This was the first time performance artists could work together and exchange ideas in Iraq. They were so happy and full of ideas.”

The highlight, he says, was the workshop Babil Performance Art conducted in the College of Fine Arts at the University of Babylon, where students are confined to learning painting and sculpture.

The art schools in Iraq have not updated their curriculum in 50 years… We always tell our artists, be two people: one inside art school, and one who creates beyond itHelen Mewis, Takrib art platform

“The art schools in Iraq have not updated their curriculum in 50 years,” Mewis says. “They teach you the technique but not how to be creative. We always tell our artists, be two people: one inside art school, and one who creates beyond it.”

The turgid educational system is just one of the challenges facing Baghdad. Its institutional infrastructure has been hollowed out, and the older generation cleaves to power, not just at the art academies but in commercial galleries and the influential Artists’ Union, which determines shows at the Gulbenkian Collection, Baghdad’s de facto national art centre. New galleries, including the leading space, The Gallery, have opened in the culturally rich Karrada area of the city, but many see their programmes as stuck in the past. The country’s National Museum of Modern Art was severely looted during the 2003 American invasion and it is now utterly dilapidated. While some paintings have returned, they are not taken care of—one visiting curator saw water dripping from the ceilings on important works in the art storeroom of the ministry of culture.

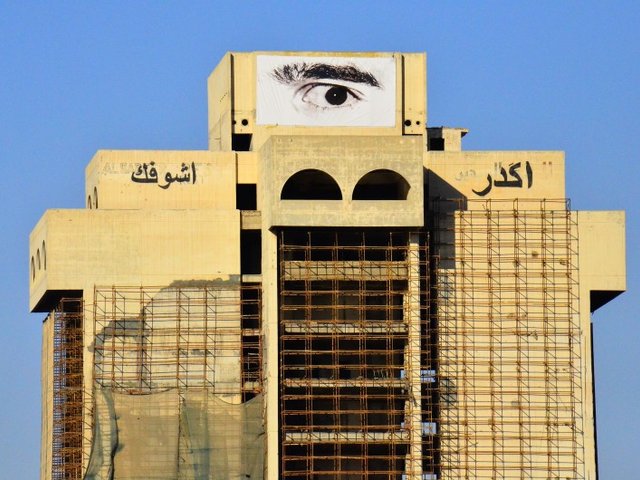

Most important is the funding situation. Financial support from the ministry of culture is next to zero, and the little funding that exists goes to the kind of public art that serves as propaganda—a holdover from the Saddam Hussein era. Other forms of funding and patronage entail political compromise, with links to different factions in the still intensely sectarian society. For this reason, both Tarkib and Babil Performance Art refuse to accept public funds.

But independence is not an easy path. Tamara Chalabi, one of the co-founders of the non-profit Ruya Foundation, which runs a gallery in Mutanabbi Street and is the commissioner of the Iraqi pavilion at the Venice Biennale, describes a constant battle to raise funds. “Baghdad and Iraq provide very rich material for reflective, sensitive, inquisitive artists,” she says. “But the infrastructure is not there. There is no local support, no collectors, and a strange resistance to the contemporary global art world. We have miles and miles to go.”

New art spaces are emerging in the city of Sulaymaniyah

The London-based Kurdish artist Walid Siti, who studied in Baghdad, says Iraqi Kurdistan is what Iraq might be in ten years’ time in terms of art school curriculum, quality of exhibitions, and international exchange. Iraqi Kurdistan was spared much of the violence of Iraq’s civil war and has had longer to benefit from a secure political situation. But it still suffers from funding and patronage being attached to political parties. The Old Tobacco Factory, a 60,000 sq. ft art centre in the middle of the city of Sulaymaniyah, survived a struggle against developers’ takeover, but has not become the independent art centre many hoped for.

Nevertheless, new spaces are emerging there too, and are actively adapting to the local context to supply what is missing. Six years ago, the young collector Shad Abdulkarim had the goal of opening a private museum for his collection, to be based in Sulaymaniyah, his home city. In the intervening years, however, he realised that Sulaymaniyah needed above all spaces that bolster the art scene’s self-sufficiency.

“We are trying to do something non-partisan and not at all politically related or fuelled, and that is quite difficult, because that’s what the infrastructure supports,” Abdulkarim says. “So the project became about: how do we raise an independent community which supports other independent spaces, void of politics, void of NGOs, and how do we do this when art and culture is still at a survival mindset and position in Iraq? Because most people in arts and culture here are just trying to survive.”

Now called Miraz Art Space, it occupies the top two floors of a cinema complex, which is owned by his father. The gallery will show part of his collection and operate commercially—allowing local and regional artists to sell work and, he hopes, to instill the idea of collecting among the country’s wealthy elite.

A recent opening at the Miraz Art Space Photo: © Birawar Najm

Siti, who has lived in London since 1984 but regularly returns to work in Kurdistan, says a mind shift is needed. He recently curated an exhibition, Lost and Found, in the northern city of Duhok, with the archaeologist Kovan Ihsan, in which Iraqi and Kurdish artists investigated their relationship to the area’s ancient past. For Siti, the problem that young artists face is not just infrastructural but existential, with the economy booming but culture not yet a priority.

“Because of the many years of deprivation and violence, everybody has now, unfortunately, plunged into consumerism,” he says. “Because parents were involved in wars, or were victims, they are spoiling their children without consciousness of where they’re going. It’s all happened very fast, without thought of the consequences. It’s like a rug being taken from under their feet.”