The wars and migrant crises currently roiling the world have given renewed poignancy to Ship of Tolerance (2005-present), an international art project to unite children created two decades ago by the late conceptualist artist Ilya Kabakov (who died in 2023) and his wife and creative partner Emilia Kabakov, who has carried on their work.

The project’s latest iteration opened on 31 May at Oakville Galleries on Lake Ontario, near Toronto, amid US President Donald Trump’s threats of annexing Canada. It is part of an exhibition of the Kabakovs’ work at the gallery, Between Heaven and Earth (until 20 September). (The duo’s work is also the subject of a concurrent exhibition, Kammermusik, at Thaddaeus Ropac in Salzburg, until 19 July.)

Over the years, carpenters from Manchester, England have built a 60ft-long wooden ship at more than a dozen locations around the world, from the inaugural version in Siwa, Egypt to the Venice Biennale, Sharjah, Brooklyn, Miami, Moscow and London. The installation is based on an ancient Egyptian boat design. Children from diverse backgrounds, initially divided by geopolitical and social conflicts, racism and sexism, gather for workshops to create paintings that are joined to create the sails of the vessel. The accompanying programmes also feature music.

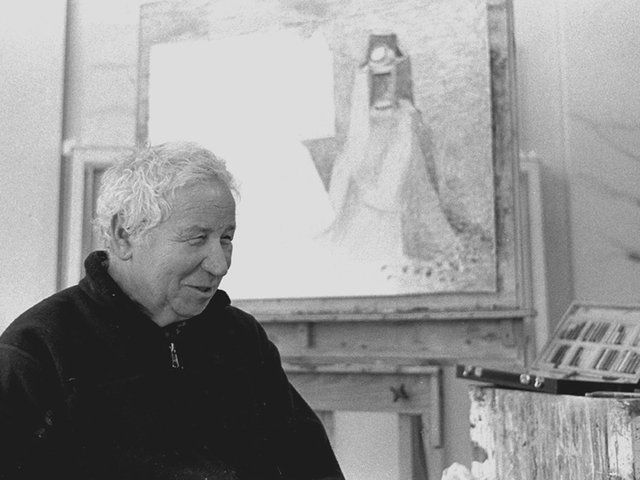

Emilia Kabakov and the carpenters who assembled The Ship of Tolerance (2005-present) at the Oakville Galleries in Ontario Photo courtesy Emilia Kabakov

The Kabakovs were born in Ukraine and educated in Moscow, which is where Ilya Kabakov first became famous. He spent part of his childhood in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Both from a Jewish background, the Kabakovs were also related to each other. Their collaboration as artists began as emigrés in New York.

Kabakov tells The Art Newspaper by email that amid the escalation of the conflict between Israel and Iran at least two more Middle Eastern countries extended invitations to her, underscoring the relevance of Ship of Tolerance.

“It’s very easy to start wars, but it’s incredibly difficult to stop them,” she writes. “I hope that our project will turn thousands of kids, and even their parents, away from trying to solve problems with violence.”

She says the project’s “fantastic success in Canada” is fuelling her determination to bring Ship of Tolerance to new audiences.

Children create paintings to form the sail of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov‘s The Ship of Tolerance (2005-present) during a workshop at the Oakville Galleries in Ontario Photo by Jono & Laynie, courtesy Oakville Galleries

“Maybe it was because of the diversity of population there, or maybe it’s just that at this particular moment people really want to be together and are worried about the future of this world and the fate of their children in that world, but thousands of visitors are coming to see the ship every day,” she writes. “Groups of children continue to hold conversations on tolerance by the ship. And what for me is one of the most important things right now is that all our plans for this and the next year in the Middle East and Asia, are still going ahead.”

Next year, Kabakov tells The Art Newspaper, a permanent version of the ship will be put up in Siwa as a monument to tolerance. She adds that when the project started there in 2005, working on the ship was the first opportunity offered to girls for a social role other than being “material to marry and give birth”.

This autumn Kabakov will be at the inaugural Bukhara Biennial in Uzbekistan and will bring Ship of Tolerance to ancient Samarkand, where it will coincide with the 43rd session of Unesco’s General Conference and bring together children from Russia, the US, Canada and Saudi Arabia. She is also planning to organise a concert of Uzbek, Russian, American, Canadian and Saudi Arabian children, and says she is in talks to bring the ship to Saudi Arabia next year.

Children create paintings to form the sail of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov‘s The Ship of Tolerance (2005-present) during a workshop at the Oakville Galleries in Ontario Photo by Jono & Laynie, courtesy Oakville Galleries

She says the most logistically complicated iteration of The Ship of Tolerance to date was in Havana in 2012. The project initially met with vociferous objections from the US State Department and Cuban emigrés in Miami. Materials had to be transported via Canada and the State Department tried to block American children from participating. Ultimately US authorities gave the green light for students from LaGuardia High School in New York—where the Kabakovs’ grandchildren were students—to take part. The Russian Embassy in Havana sent children who made anti-American art.

Kabakov says that her suggestion that children could sail on the boat from Havana to Miami and back infuriated the Miami-based collector Rosa de la Cruz, who had fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba. De la Cruz accused Kabakov of being willing to speak with Stalin and Hitler. Kabakov flew to Miami to explain (and demonstrate) her position of seizing on any opportunity for dialogue.

“I would speak with Stalin and Hitler, and maybe what happened would not have happened if someone sat down to speak with them,” Kabakov recalls telling De la Cruz, with whom she found common ground following the conversation.

For now, she has no plans to take the ship to the country of her birth, Ukraine, because of the impossibility of security guarantees. Many years ago, she had wanted to do a version of the project in Ramallah in the West Bank, until the Kabakovs started receiving death threats by fax. She adds: “I can risk my life, but not the lives of children.”

- Ilya & Emilia Kabakov: Between Heaven and Earth, until 20 September, Oakville Galleries, Canada