When the new, career-defining survey of Gustave Caillebotte opened in late June at its final stop, the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), the checklist was very similar to previous versions at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Its chronological layout will also be familiar to any return visitors. But the show is dramatically different in at least one respect: its title.

The Midwestern institution has changed the exhibition title from Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men (in French, Caillebotte: Peindre Les Hommes) to the more gender-neutral—or neutered—Gustave Caillebotte: Painting His World (until 5 October). Could it be that the Chicago museum is toning things down because so many French art critics flipped out over the male focus?

AIC curator Gloria Groom explains the change was made before the show even opened in Paris, after an internal focus group revealed that the “Painting Men” title sounded too narrow. “Out of the titles we could come up with, [‘Painting His World’] seemed to be the one that was most attractive,” says Groom, who co-curated the show with Paul Perrin of the Musée d’Orsay and Scott Allan of the Getty. (She says it was also a good fit for the AIC’s beloved 1877 Caillebotte, Paris Street, Rainy Day, showing a heterosexual couple strolling arm-in-arm.)

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877. The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. Worcester Collection.

Either way, the exhibition is likely to land differently in Chicago than it has in Paris and Los Angeles, where responses say more about that city’s art critics than the show itself. In Paris, several prominent newspaper columnists panned the show for being a reductive, American-tainted and wholly unjustified exercise in queering the artist. In Los Angeles, many critics appreciated the curators’ subtle exploration of the artistic themes of virility, fraternity and homosociality, bordering on or possibly obscuring homosexuality. You would think they were seeing two completely different shows.

The curators all said in phone interviews they were surprised by the vehemence of the Paris reviews, especially considering they never made the case that Caillebotte had sexual relationships with men. Rather, they made it clear that he lived with a female partner, Charlotte Berthier, and left her a sizable annuity on his death.

“When we started out, we thought we might be criticised for dancing around the question of the artist’s sexuality—for not going there forcefully enough,” says Allan. Instead, they saw the opposite response play out on French soil. “It was a little surprising to see that kind of reaction—I thought this is 2024 or 2025, not 1990.”

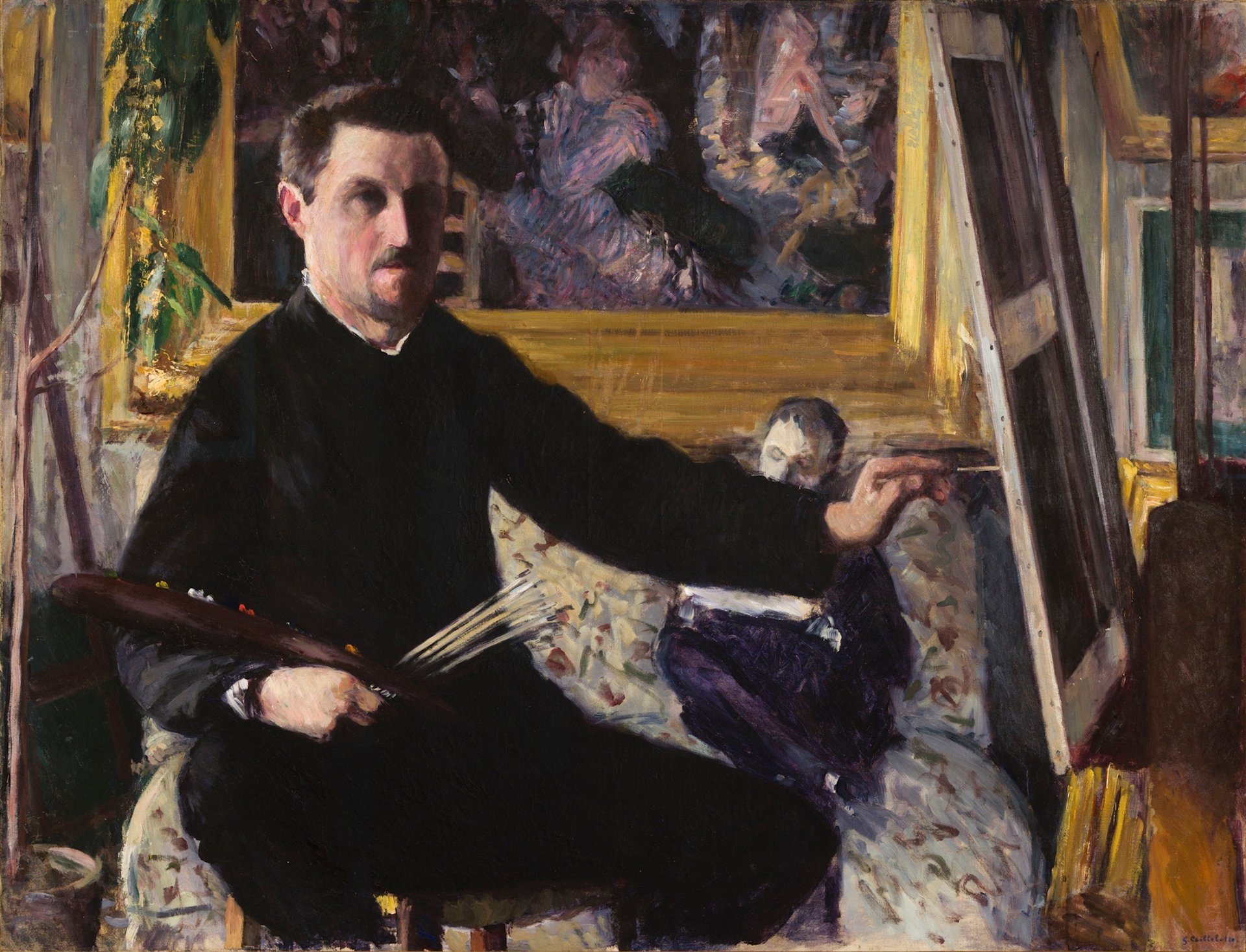

Gustave Caillebotte, Self-Portrait at the Easel, 1879. Private collection, France. Photo © Caroline Coyner Photography.

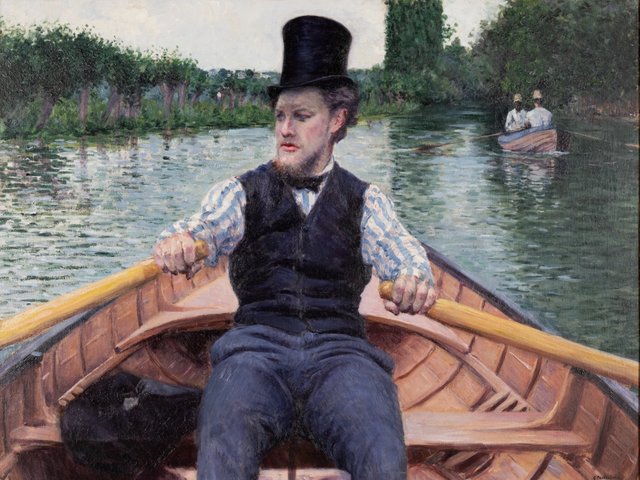

The curators chose their focus because of Caillebotte’s own preference for men as subjects and recent scholarship on the issue. Unlike his Impressionist counterparts who depicted women in all stages of petticoat-covered dress and undress, Caillebotte tended to paint groups of men engaged in the activities he enjoyed, including rowing, sailboat racing, military drills, card-playing and urban spectatorship. It is not just a matter of quantity, but quality, adds Perrin: “The most ambitious work of other Impressionist is usually women; Caillebotte’s most ambitious work was men.”

As Groom points out, Caillebotte’s wealth allowed him the privilege of bucking the trend and choosing male subjects, without regard for what would sell. Born in Paris in 1848 to a family in the textile business, he began his professional life by studying law, before switching tracks to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. “He’s from a family of three brothers, he goes to an all-boys school, goes to law school with all men, art school with men and joins the Impressionists who with two exceptions are all male,” she says.

One of his early paintings, which made its debut at the second Impressionist-organised Salon des Indépendants, has been a lightning rod for debate: Les Raboteurs de Parquet, or The Floor Sanders (1875). Painted from an elevated perspective, it features three shirtless, muscled men who are bending over Caillebotte’s studio floor and working up a sweat. Their bare backs gleam like the varnish on the floor itself. The painting is sensual and, in its depiction of working-class men, political, inviting interpretation about capitalism, labour and leisure—and male sexuality.

An ‘invitation to homoerotic viewing’

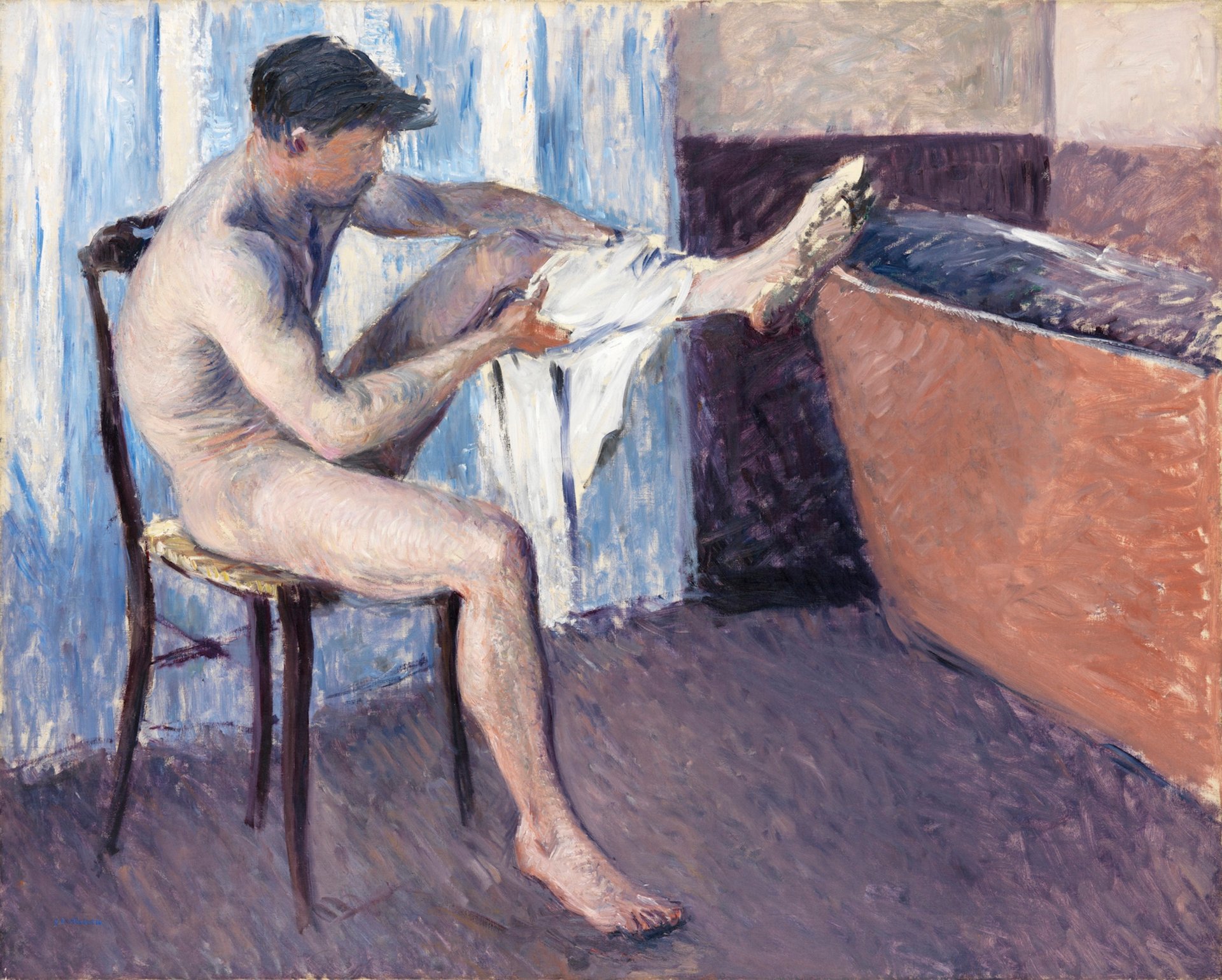

Gustave Caillebotte, Man Drying His Leg, around 1884. Private collection. Photo by Lea Gryze, Berlin. © Private collection, Berlin, 2024.

Another painting that has attracted intense attention is Man at his Bath (1884), which spotlights, unlike Degas or Renoir’s dreamy female bathers, a realistically rendered man who has just emerged from a bath. He is shown drying himself off with a towel that reveals more than it conceals. He is painted from behind, his buttocks visible. In their catalogue essay, the University of Pennsylvania scholars André Dombrowski and Jonathan Katz describe the “libidinal dynamics” and “invitation to homoerotic viewing unleashed by the painting itself”, analysing what they call “his paintings’ sexuality”.

Harry Bellet called this notion “complete nonsense” in Le Monde: “The sexuality of the painting, one would think they were talking about Jeff Koons!” As for Les Raboteurs, he described the elevated perspective as extreme realism and the painting itself as “almost classical”. Philippe Lançon in Libération bemoaned “the battleship of gender studies” crossing the Atlantic from America, while Eric Biétry-Rivierre at Le Figaro argued that the Musée d’Orsay was operating “under the influence” of its American museum partners.

Gustave Caillebotte, Balcony, around 1880. Private collection. Photo courtesy of the private collection/Bridgeman Images

Note that all of these French critics are men—“and all over the age of 50”, adds Perrin. He sounded amused by the way they blame his American co-curators, when in fact he originated the show’s masculine emphasis and helped historicise it as a response to the vulnerability felt widely in France in the wake of the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian war.

The response in the States ranged from explicitly queer readings of Caillebotte’s work in LGBTQ+ publications to more complicated reviews by critics such as Christopher Knight at the Los Angeles Times and James Meyer at Artforum, both of whom discussed the ambiguity of the paintings.

“We will never know what Caillebotte felt for his oarsman, or if his feelings were returned,” Meyer wrote, responding to what he called “the pearl-clutching reviewer” at Le Figaro. “It may be that his paintings are precisely structured to frustrate such speculation.”

“And so we are compelled to look at them,” Meyer continued. “At a time when rigid definitions of gender and sexuality have been destabilised, and allegations of a ‘crisis of masculinity’ fuel the propaganda campaigns of right-wing politicians and authoritarian regimes, the art of this once devalued painter feels astonishingly relevant.”

- Gustave Caillebotte: Painting His World, Art Institute of Chicago, until 5 October