Berlin Atonal defies the conventions of both a festival and an exhibition. It does not follow a unifying curatorial theme; instead, the experience is driven by sound and its interaction with space, operating more like a rave than a white cube exhibition.

The event was recently recognised by the Biennial Foundation as the first biennial “rooted in music and sound”, leading to questions about what it means to centre experimental sound in a visual culture setting. And the timing of this recognition was not incidental—in 2024 Berlin’s techno culture was added to Germany’s register of UNESCO cultural heritage.

With this year’s festival sold out on the usually music-focused ticketing platform Resident Advisor, the need to collapse the categorisation of art, music, and film is clear. But how successfully does Atonal push the boundaries of visual culture, and where does this sit within a Berlin increasingly defined by censorship and political oversight?

“The music feels really big”

For the festival’s co-director Laurens von Oswald, the programme’s defiance of neat categorisation is deliberate. “What is a music festival, what is an art exhibition? Why are these categories so fixed? Should they be?” he asks.

“One thing we’ve been obsessed with is attention: how people experience things in the moment. A lot of what happens at the festival is created on-site, in the space, often at the very last moment. It’s alive and chaotic in a good way.”

The Kraftwerk building, a decommissioned power station, shapes Atonal’s atmosphere. On entering, visitors are dwarfed by concrete as sound thrums through the air. “You just feel extremely small, and the music feels really big,” says artist Billy Bultheel.

Speaking of his new work Fugue State, the second chapter in his Short History of Decay series, he continues: “I love to work with space as an instrument itself in my work.” Meanwhile Four musicians and one electronics operator play a self-built instrument modelled on a medieval resonating urn, resulting in an atmospheric, sonic pressure system for the audience to inhabit.

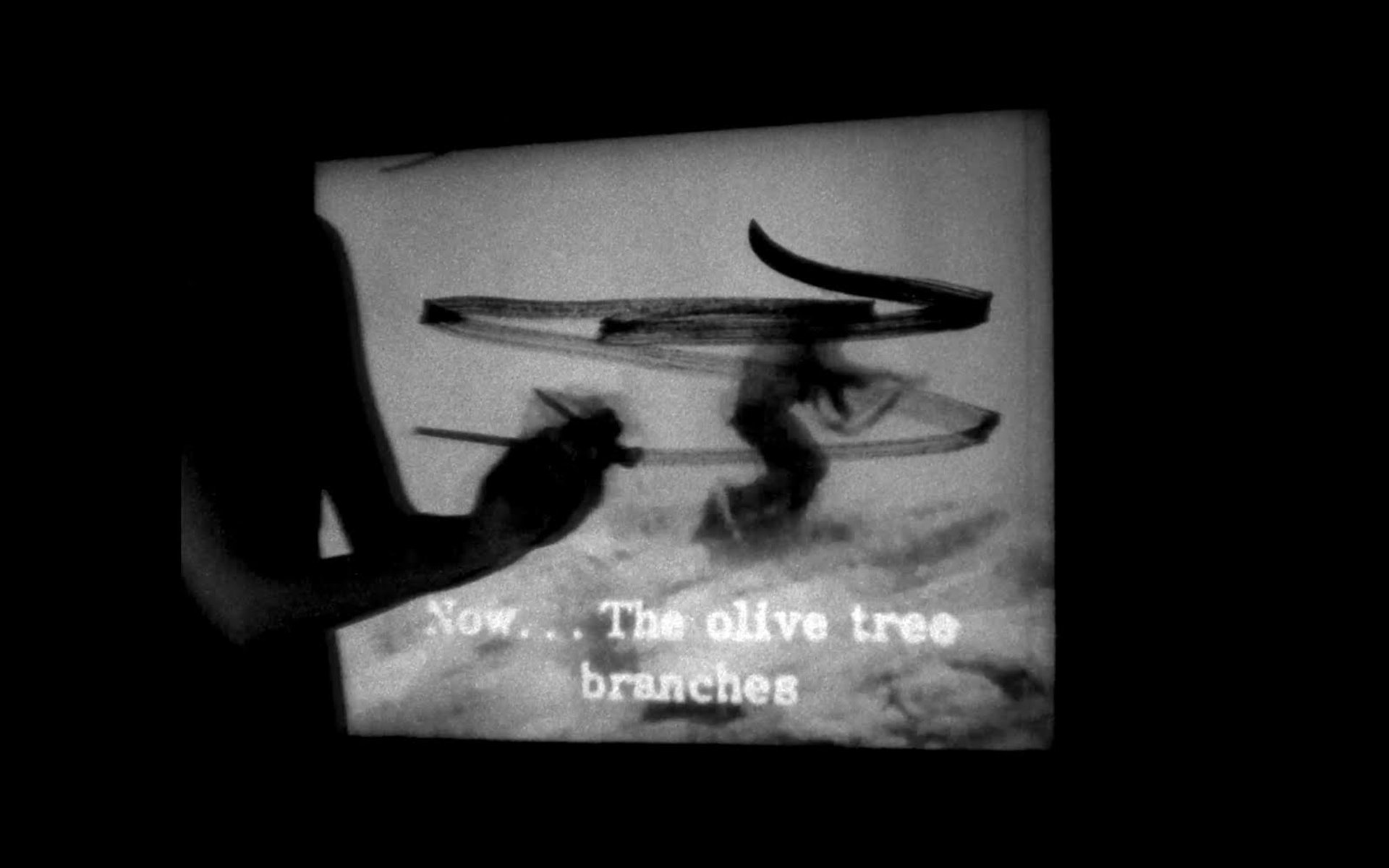

Kamal Al Jafari, School

Courtesy of Artist

The physical and the temporal

Atonal thrives in the intersections: one moment a concert, the next an installation, and then something entirely in-between. In its 3rd Space setting, artists including Anne Imhof, Cyprien Gaillard and Mohamed Bourouissa are brought together across the five festival nights, with some listening rooms in the former power station control rooms. Unlike a conventional gallery, Atonal recalibrates duration, asking visitors to experience sound as a physical and temporal experience.

“We treat sound as a fully legitimate art form—not background, but central,” says von Oswald. “Our background is in sound, and over time we realised how much sound influences artists who usually work in the visual arts. Many of them dream of presenting their work to thousands of people, instead of the small trickle [of sound] you get in a gallery.”

Basma AlSharif, O'PERSECUTED

Courtesy of Artist

Political pressure

In recent months, cultural institutions across Germany considered to be supportive of Palestinian artists and causes have come under mounting political scrutiny. Participating Palestinian artist Basma al-Sharif, whose work encompasses film, installation, and performance, is acutely aware of this climate. Her 2014 film O’Persecuted, part of Atonal’s programme, resonates today.

“When I moved [to Berlin], I didn’t understand how hostile the terrain really was,” she says. “After [the Israel-Hamas war began on 7 October 2023] I realised it’s far more violent and aggressively aimed at silencing narratives. The hardest blow has been in the cultural sector. Berlin had been a beacon of freedom of speech. Since [the war began], it’s been a wasteland.”

Al-Sharif’s work is presented at Atonal alongside peers such as Noor Abed and Kamal Aljafari. “Our work isn’t just being pigeonholed as political commentary—it’s engaged with as art, ” she says.

Ultimately, Atonal is less a radical rethinking of visual culture than a reconfiguration of how cultural production is organised and consumed. By refusing the thematic model, it sidesteps the didacticism of many biennials, offering instead a looser constellation of works, atmospheres, and intensities. For some, this ambiguity may feel evasive; for others, it resonates with a cultural present defined by collapse and hybridity.

If the biennial form is in crisis, then Atonal’s refusal to fix meaning in place might be its most boundary-pushing gesture. Not a solution, but a refusal to thematise, and in its place, a terrain of sound, space, and movement in which audiences must orient themselves. And, although this orientation feels unresolved, this may be precisely the point.

- Berlin Atonal, Kraftwerk, Berlin, until 31 August