London’s Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers exhibition, which closed at the National Gallery earlier this year, offered the chance to see how the artist’s works have been framed by their fortunate owners. With loans from nearly 50 museums and private collections, nearly all the paintings were displayed in ornate gilded frames—which Van Gogh disliked.

Van Gogh’s The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy) (December 1889) in a typical example of a French Baroque gilded frame—it has been on the painting since it was sold by the dealer Paul Rosenberg in 1947

Cleveland Museum of Art (photograph The Art Newspaper)

Although most exhibition visitors probably do not consciously notice framing, it does have a substantial visual and psychological impact on how we view paintings. It is also a fascinating and relatively little-studied aspect of art history.

Van Gogh favoured wooden frames without carved ornament, with a plain design, occasionally painted. As Vincent put it to his sister Wil: “If the painting looks good in a simple frame, why put gilding around it?”

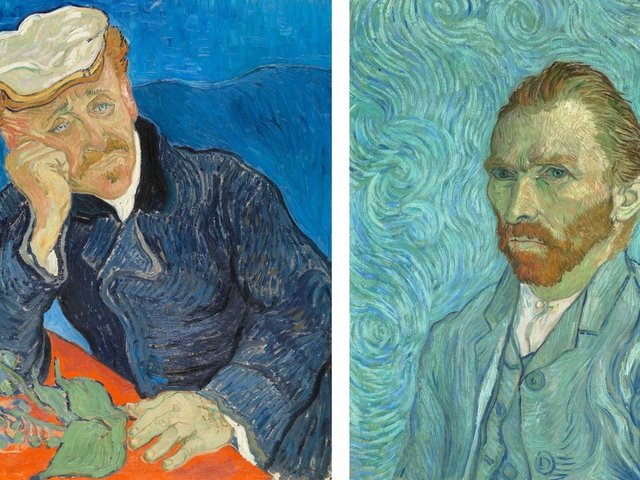

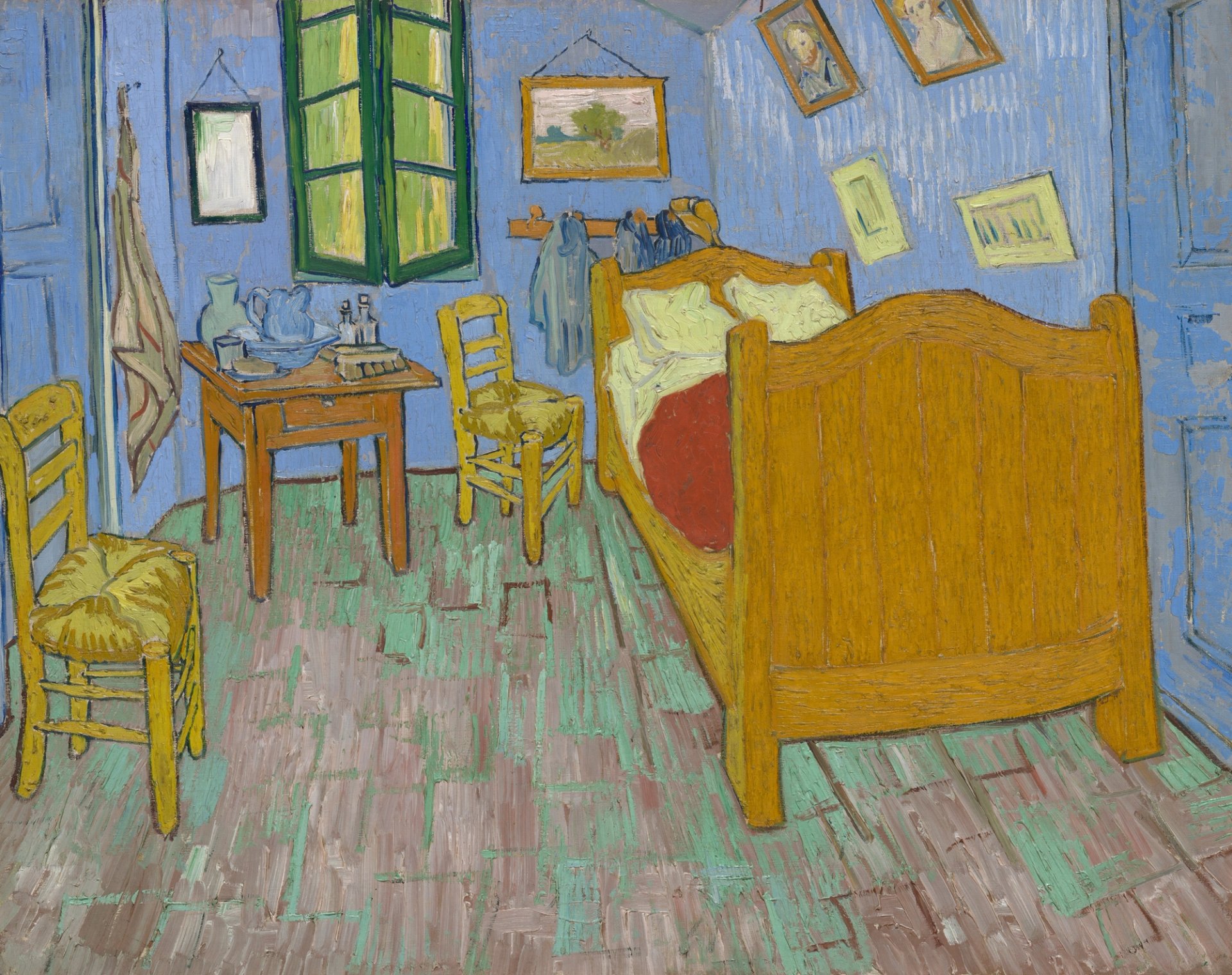

His own idea of framing can be seen in one of his paintings which was in the National Gallery exhibition, the version of The Bedroom (September 1889) from Chicago. Just above the artist’s bed he depicted what is probably an imaginary landscape scene, framed simply in natural wood and rather crudely hanging from a string or wire on a nail.

Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (September 1889)

Art Institute of Chicago (Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, 1926.417)

From the early 1900s Van Gogh’s paintings were beginning to sell and dealers started framing them to match buyers’ expectations, giving him the status of an established “master”. This angered Paul Gachet Jr, the son of the doctor who in 1890 had cared for the artist at the end of his life. In 1905 Gachet Jr complained that “it is an act of moral barbarism to put gold frames around Vincent’s canvases, that simple, humble man”.

Unusual frames

Amidst the sea of gilded frames in the National Gallery exhibition there were a handful or so of rather different ones which are worthy of note. It is interesting to explore these few examples which break away from the traditional ornate framing which Van Gogh disliked.

Most distinctive of all were the six paintings on loan from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, in the east of the Netherlands. These included the fine landscape Tree Trunks in the Grass (April 1890).

Van Gogh’s Tree Trunks in the Grass (April 1890), in its Jacob van den Bosch replica frame

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (photograph The Art Newspaper)

The museum’s wooden frames, with slightly raised square corners, are replicas of the early frames which Helene Kröller-Müller commissioned from around 1910 for her important Van Gogh collection. Designed by the Dutch interior decorator Jacob van den Bosch, they are in an early Art Deco style.

Virtually all the Van den Bosch frames were discarded in 1950s, to be replaced with inexpensive linen-edged frames simply bought from an art shop. In the 1980s some Van Goghs were reframed again, to a design by the architect Wim Quist. After a few years neither the 1950s nor the 1980s replacements were regarded as satisfactory.

Finally in 2003-05 it was decided to revert to the design of the Van den Bosch frames, which had survived on two or three paintings, including a 1920s forgery, Seascape at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Replica frames were made from the these templates, so the museum’s collection of Van Gogh paintings is now presented in this way.

Van Gogh’s Roses (April 1889), in its antique gilded frame and its new replica Gachet frame

National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo (photographs by The Art Newspaper)

A Van Gogh from Japan on loan to the London exhibition had a replica frame based on an even more important historical example. Tokyo’s National Museum of Western Art decided to reframe their Roses (April 1889) especially for the show, based on an example that was once in the collection of Dr Paul Gachet.

A few years ago some empty frames once owned by the doctor were discovered, abandoned with a neighbour. On the back of one of them was an inscription recording that it had once held another Van Gogh landscape.

Roses had been owned by Dr Gachet, sold off by his son in 1923, then bought by the distinguished Japanese collector Kojiro Matsukata and eventually acquired by the National Museum of Western Art. It therefore seemed appropriate to reframe it in the style which the doctor had used.

Van Gogh’s Mountains at Saint-Rémy (July 1889), in its 17th-century black Italian frame

Soloman R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (Thannhauser Collection)

Mountains at Saint-Rémy (July 1889), from New York’s Soloman R. Guggenheim Museum, demonstrates the challenges of framing a Van Gogh. Its early frames are unrecorded, but when in 1965 it was donated to the museum by the dealer Justin Thannhauser it came in an ornate 17th-or 18th-century gilded frame. This was changed soon after its arrival and again in 2007, but neither replacement frame was successful.

In 2016 it was decided to use a 17th-century black Italian frame with subtle gold marks. The curvature of Van Gogh’s brushstrokes is softly echoed by the decorative patterning of this frame. In the National Gallery exhibition it stood out as successful framing.

Van Gogh’s Still Life with Coffee Pot (May 1888), with its red and white painted ‘frame’ included by the artist

Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation, Athens

Interestingly, in one of the pictures in the show Van Gogh has inserted his own trompe-l’oeil ‘frame’. In Still Life with Coffee Pot (May 1888) he painted a thin red border around the edge of his composition, then adding a wider white border around that.

Van Gogh would presumably have hung the still life on the whitewashed walls of his house in Arles, possibly without a simple strip frame so that the white canvas on the edges would have visually blended in with the room. I have always imagined that he would have displayed the painting in his kitchen, close to his coffee pot and crockery.

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers: Philadelphia’s version in its previous French Baroque gilded frame and in the new simpler frame in the National Gallery exhibition

Philadelphia Museum of Art (London frame photographed by The Art Newspaper)

The London exhibition’s greatest success had been to recreate one of Van Gogh’s “triptychs”, by showing two of his versions of Sunflowers on either side of La Berceuse (The Lullaby) (January 1889).

The National Gallery’s Sunflowers with a yellow background (August 1888) is in a fairly simple 17th-century Italian frame which is slightly distressed—old woodworm holes, from insects long dead, can be seen on close inspection.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art's still life on a blue background has long been in an ornate gilded frame, probably added by its previous owner, the artist Carroll Tyson and his wife, who donated the masterpiece in 1963. Together, the two very different frames as part of a triptych would have produced a jarring effect.

Philadelphia’s solution was to reframe its painting in a similar frame to that of the London Sunflowers for the exhibition. It is deliberately not an exact replica of the London frame, since the decorative marks are slightly different, but from a distance most viewers would feel they were the same.

Although the new Philadelphia frame is not the simple wooden strips which Van Gogh had envisaged, he would probably have preferred it to a gilded example. When the painting returned after the London exhibition, the Philadelphia curators decided to retain the simpler frame.

Other Van Gogh news

On 27 August Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum issued a tough statement, saying it is at risk of closure unless the Dutch ministry of culture provides an increased grant to help finance the maintenance of its buildings. Director Emilie Gordenker said that with the funding the museum “will not be able to guarantee the safety of the collection, visitors and staff”. She argues that the Dutch government is breaking a 1962 agreement with the Van Gogh family, and it is obliged to assist. The museum is taking legal action against the government, with the issue due to come to court on 19 February 2026.

REVISED: Originally published on 17 January 2025, this blog post was updated with new information on 29 August.