“I was driving at about 15 miles an hour, with my nose practically up against the windshield, looking for things to photograph,” says the US photographer Sally Mann. She is talking about a recent trip to the Mississippi Delta, where she was shooting for the first time with a nifty little digital camera. “I was stopping every 100 yards and taking pictures—some industrial, some landscapes, some dead animals in the road. I didn’t know what I was doing. I had no idea. And the people behind me were honking, thinking, ‘What a crazy fruit bat, driving her car like an old woman’. Which of course, I am.”

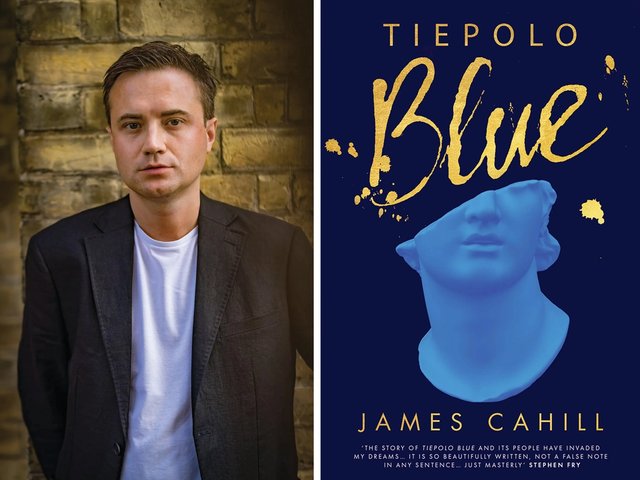

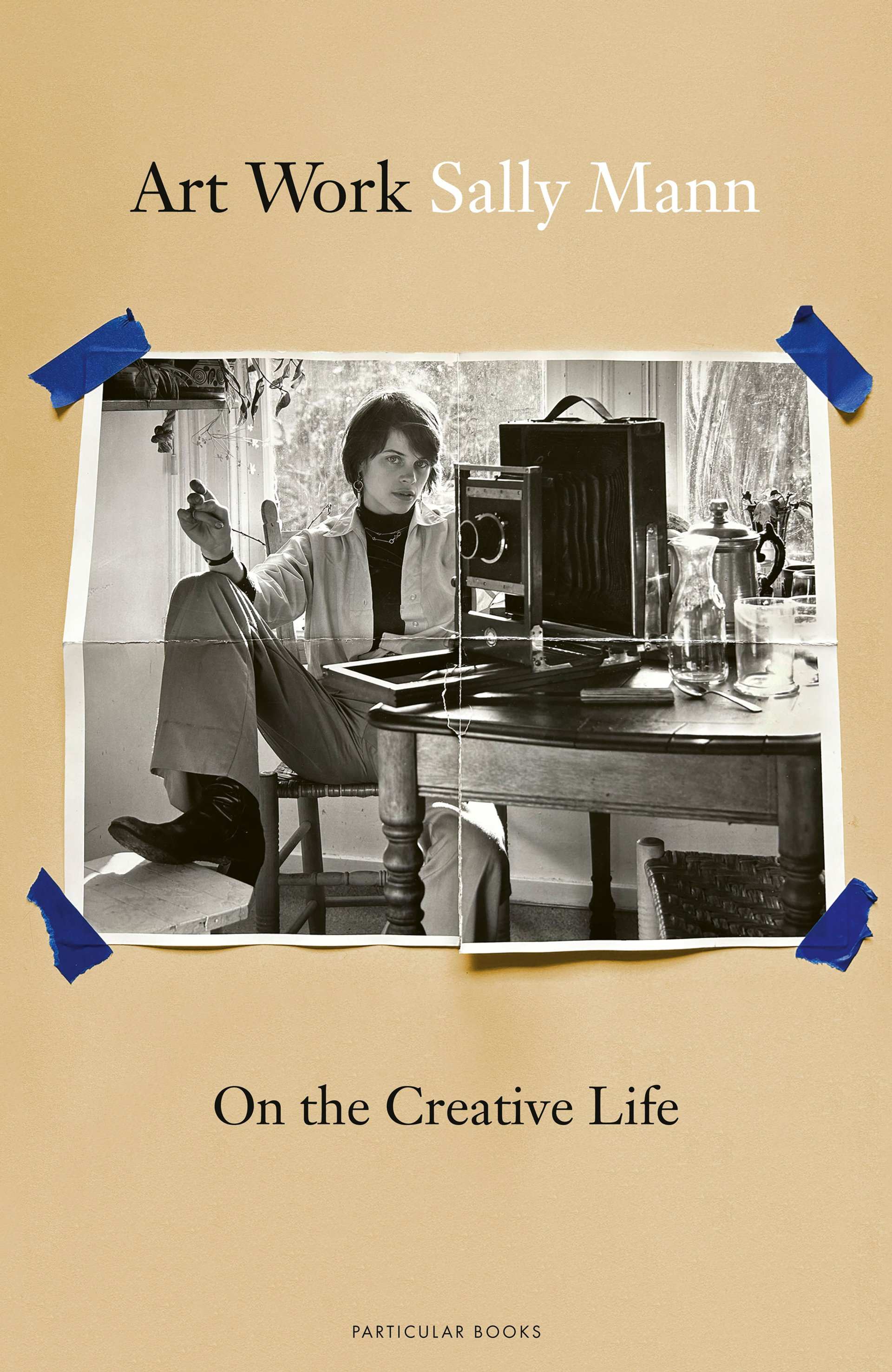

Mann is speaking ahead of the publication of her new book, Art Work: On the Creative Life, from the family farm where she grew up in Lexington, Virginia. She describes the book as “kind of a how-to book, or a how-I-did-it book—a don’t-try-this-at-home book”. The nimble mix of memoir and practical advice for artists and writers, illustrated with images, letters and diary entries, is ostensibly about making art. But it is also crucially about all the other stuff that surrounds art and often hinders it. “I think there are some fundamental truths in there,” she says, lessons learned along the way. At 74, Mann, who typically takes mythic pictures of people and landscapes with a large-format view camera, is one of America’s most renowned—or notorious—photographers.

Sally Mann Photo: Liz Liguori

In her vivid 2015 memoir Hold Still, she wrote about the controversy sparked by the collection of images she made of her children in the 1990s, titled Immediate Family. It featured intimate black-and-white portraits of her son Emmett and her daughters Jessie and Virginia playing and posing in water and woodland, often naked. There were complaints that she had exploited her children and put them in danger. She countered that her critics simply did not understand their lifestyle, that the children spent their summers at a cabin on a river, naked all day long; in other words, the nudity was not contrived. “Back then I was defiant and defensive; I felt I was completely in the right and that these people were idiots,” she says. “Now it’s different. I don’t want to say I’m ambivalent because I’m not. I still believe in the work strongly. But, you know, I wouldn’t recommend anyone else make it now.”

In a review of Hold Still in The New York Times, Francine Prose warned that “young photographers seeking tips on how to have a big career should look elsewhere”. Whether or not Mann read that review, it would appear that, in fact, she now has ample tips to share. In At Work, she lists the “main characters” you need to make art: “luck, organisation, technique, words (on actual paper), patience, tenacity, risk-taking, moral questioning, and finding your story—or letting it find you—plus, of course, character-

building suffering”. A dozen droll and witty chapters cover everything from distraction to rejection.

As an artist, Mann argues, you have an obligation to offer a different sensibility to your viewers, but you also need to accept that your work is “up for interpretative grabs”. To begin with, she says, “all I think about is whether or not it’s going to be a good picture. That’s the only important thing. And if by some miracle it is a good picture, then I grapple with the implications.” She writes candidly about acts of censorship—and self-censorship. Following the controversy surrounding Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till in the 2017 Whitney Biennial (there were protests criticising the white artist’s decision to depict the 14-year-old boy, who had been lynched in 1955), Mann and her curator decided to pull most of her pictures of Black men from her 2018 show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

When the work does not end up on the wall, is it wasted? “It’s never wasted if you take the picture,” she says. “It’s an idea wasted if you don’t.” Her ideas are inextricably entwined with her daily life and often emerge from what she calls “time-gobbling intrusions”. “I think the children became subjects because I didn’t have any other way to make art at that time. And my friends who dropped by for a drink, I would say, ‘Well, while you’re here, would you mind wearing my mother’s wedding slip for a minute while I take a picture?’”

The cover of Sally Mann's Art Work: On the Creative Life

Whether she is behind the wheel or walking the dogs, everywhere Mann looks, she sees photographs. “Life is moving by me all the time and I’m split-second stopping it,” she says. “If I don’t have a camera with me, it can be a problem. I can’t turn it off. Like right now, I’m seeing a shaft of light and the way it intersects with the edge of your rug, and the way the fringe is lit. My eye goes to that, and I’m distracted. I’m always distracted by images.”

• Sally Mann, Art Work: On the Creative Life, Particular Books, 272pp, £25 (hb)