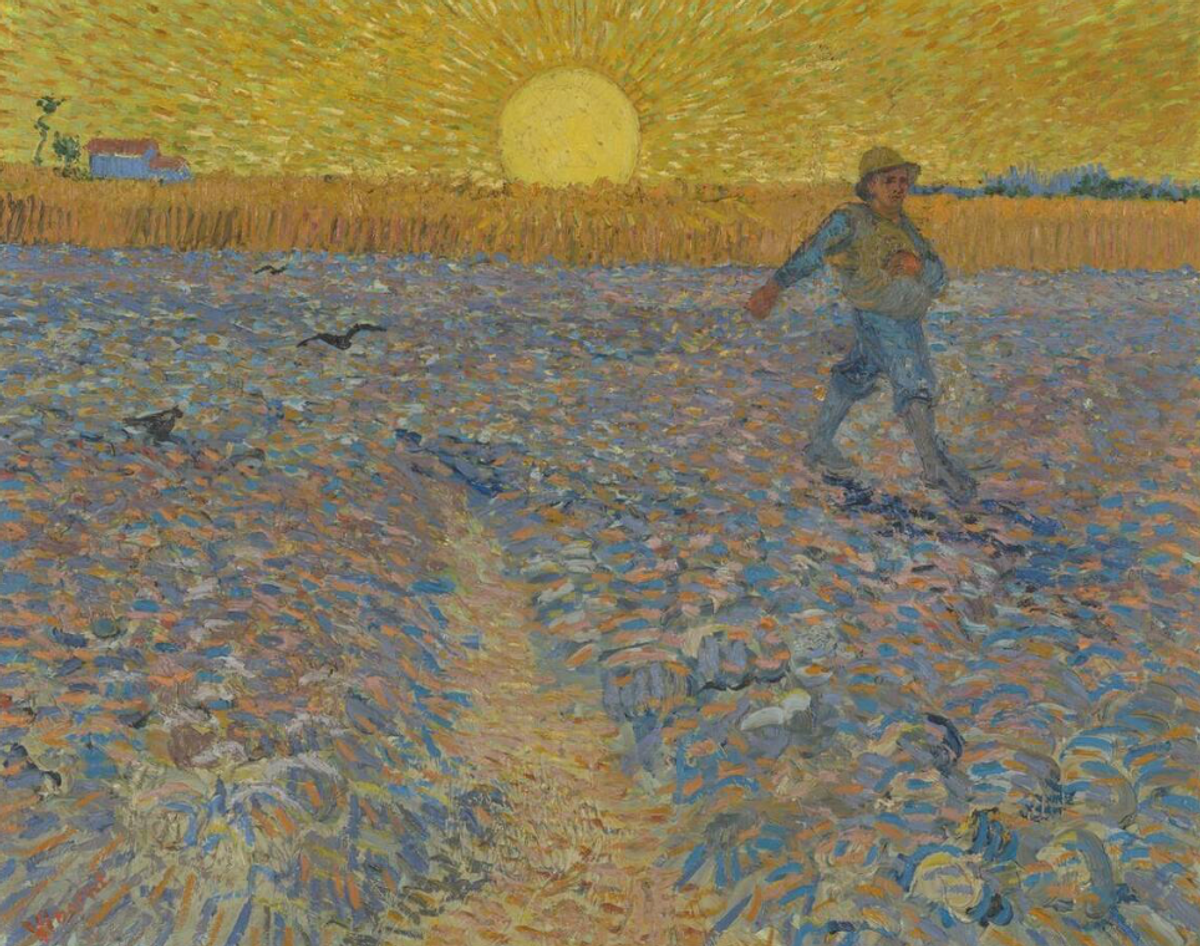

The National Gallery is tomorrow opening Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists (until 8 February 2026), with work by many of Van Gogh’s Parisian colleagues, notably Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Van Gogh was inspired by their dot-like technique, as can be seen in his vibrant painting included in the London show, The Sower (June 1888).

The Sower also has the distinction of receiving what is could be seen as a papal blessing. In his first general audience at the Vatican in May, Leo XIV talked about Christ’s Parable of the Sower, referring to Van Gogh's The Sower.

The Pope pointed out: “At the centre of the scene, however, is not the sower, who stands to the side; instead, the whole painting is dominated by the image of the sun, perhaps to remind us that it is God who moves history, even if he sometimes seems absent or distant.” Pope Leo then added that “it is the sun that warms the clods of earth and makes the seed ripen”, a spiritual thought that would certainly have resonated with Van Gogh.

Van Gogh, the son of a Dutch Protestant clergyman, was a deeply committed Christian in his early 20s. He was then non-denominational and while living in west London in 1876 he once wrote about seeing “a very beautiful little Roman Catholic church” (probably St John’s in Brentford). A few years later he totally abandoned organised religion.

The Sower and Neo-Impressionism

Van Gogh’s The Sower and Théo van Rysselberghe’s Portrait of Anna Boch in Radical Harmony at the National Gallery, London (until 8 February 2026)

The Art Newspaper

In the National Gallery’s Neo-Impressionist exhibition The Sower is there to tell a very different story, one about artistic technique. Van Gogh partly painted the composition by deploying dots and dashes in an almost pointillist style. The idea is that these small marks of pure colour should blend together in the eye of the beholder when seen from a few metres away, strengthening their impact.

Vincent discovered Neo-Impressionism after his arrival in Paris in 1886, when he was staying with his brother Theo. He met its two leading protagonists, Seurat and Signac, and admired their work. For a short time in early 1887 Van Gogh experimented with their dot-like technique. Although he soon abandoned pure Neo-Impressionism, finding it too rigid a technique, he continued to make use of small dashes of pure colour, as in The Sower, which was partly inspired by his Neo-Impressionist colleagues.

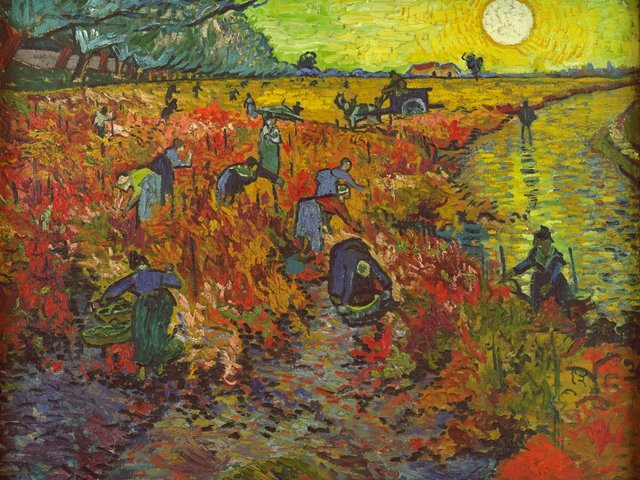

The Sower was painted in Arles, in June 1888, four months after he had left Paris. The figure of the sower was based on a well-known image he admired by the mid-19th century French artist Jean-François Millet. Van Gogh set his sower in a Provençal wheat field, beneath a powerful setting sun. In the background is the golden wheat, ready to be harvested. Sowing would not be done at the same time as harvesting, so the the two scenes have come together in Van Gogh’s vivid imagination.

Van Gogh’s painting, with its layers of meaning, surely refers to the cycle of nature and of life. It also has a religious aspect, as Leo XIV appreciated: the sower on the land represents the sower of God’s word.

The artist was hardly concerned with accurately reflecting the scene in terms of colour. Just as he was starting, Vincent wrote to Theo: “You can sense from the mere nomenclature of the tonalities—that colour plays a very important role in this composition.”

Vincent felt intimidated, telling Theo: “I just wonder whether I’ll have the necessary power of execution” to complete it. He added: “For such a long time it’s been my great desire to do a sower, but the desires I’ve had for a long time aren’t always achieved.”

Van Gogh also described the painting to his friend Emile Bernard: “There are many repetitions of yellow in the earth, neutral tones, resulting from the mixing of violet with yellow, but I could hardly give a damn about the veracity of the colours”.

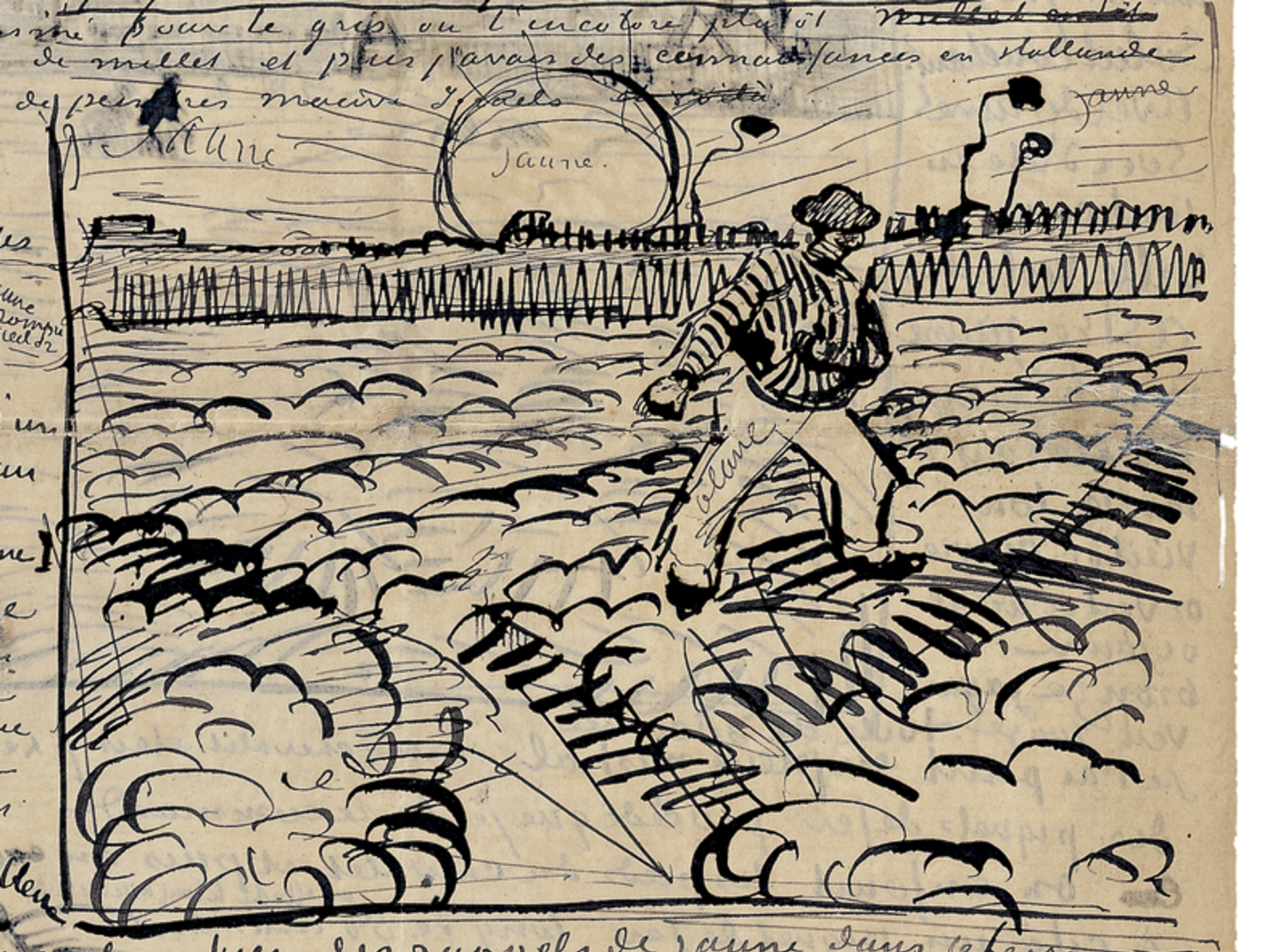

Van Gogh’s sketch of The Sower, in a letter to Emile Bernard, 19 June 1888

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Most of the composition is taken up with the bare field, with the soil made up of short orange and blue brushstrokes. These are complementary colours, giving a powerful vibrant effect.

Around the edge of The Sower, partly hidden by its present frame, is a narrow multi-coloured border painted by Van Gogh around the sides of the canvas. It is difficult to see, unless you know it is there—and look carefully. Similar painted borders had been introduced by Seurat and some of the Neo-Impressionists.

Enlargement of the lower-left corner of Van Gogh’s The Sower, out of its frame, showing the border painted by the artist

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

In 1889 Vincent suggested to Theo that The Sower would be suitable for a coming exhibition at the Société des Artistes Indépendants. Although it ultimately did not go into the show, if it had done, it would have been seen alongside Neo-Impressionist works by Seurat and Signac.

Helene Kröller-Müller’s vision

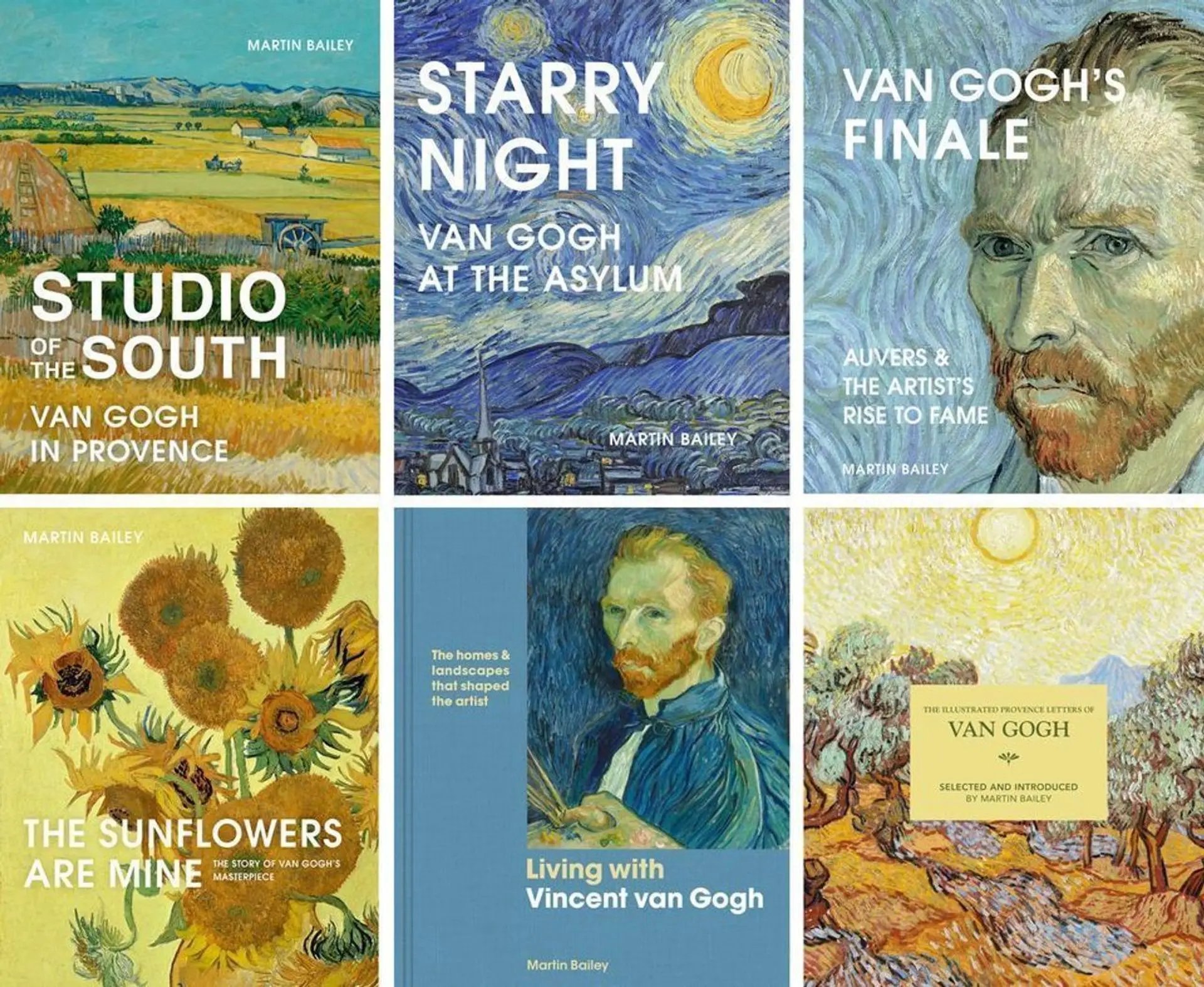

The National Gallery exhibition comprises 58 works, with nearly two thirds coming from the Kröller-Müller Museum, which is set in a national park in the east of the Netherlands (the remainder are from a wide variety of lenders). As the show’s title suggests, Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists also sets out to pay homage to the woman who built her own museum which opened to acclaim in 1938.

Helene Kröller-Müller was the first serious collector to amass an important group of Neo-Impressionists. It is now arguably the world’s greatest collection of Neo-Impressionism. She began in 1912, with a Signac, and a decade later acquired what is the centrepiece of the National Gallery’s show, Seurat’s Chahut (1889-90), with its energetic cancan dancers.

Both of Kröller-Müller’s advisors, Henk Bremmer and Henry van de Velde, were admirers of Neo-Impressionism and were themselves artists who painted in this style (two of Van de Velde’s pastels are in the London show). Van de Velde, who turned from painting to architecture, was later the designer of the Kröller-Müller Museum.

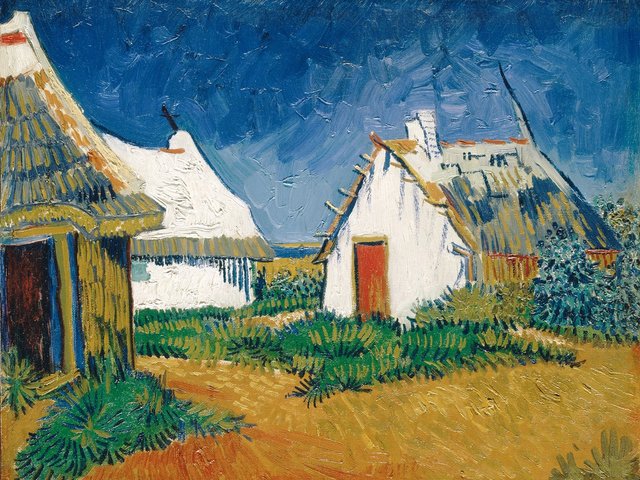

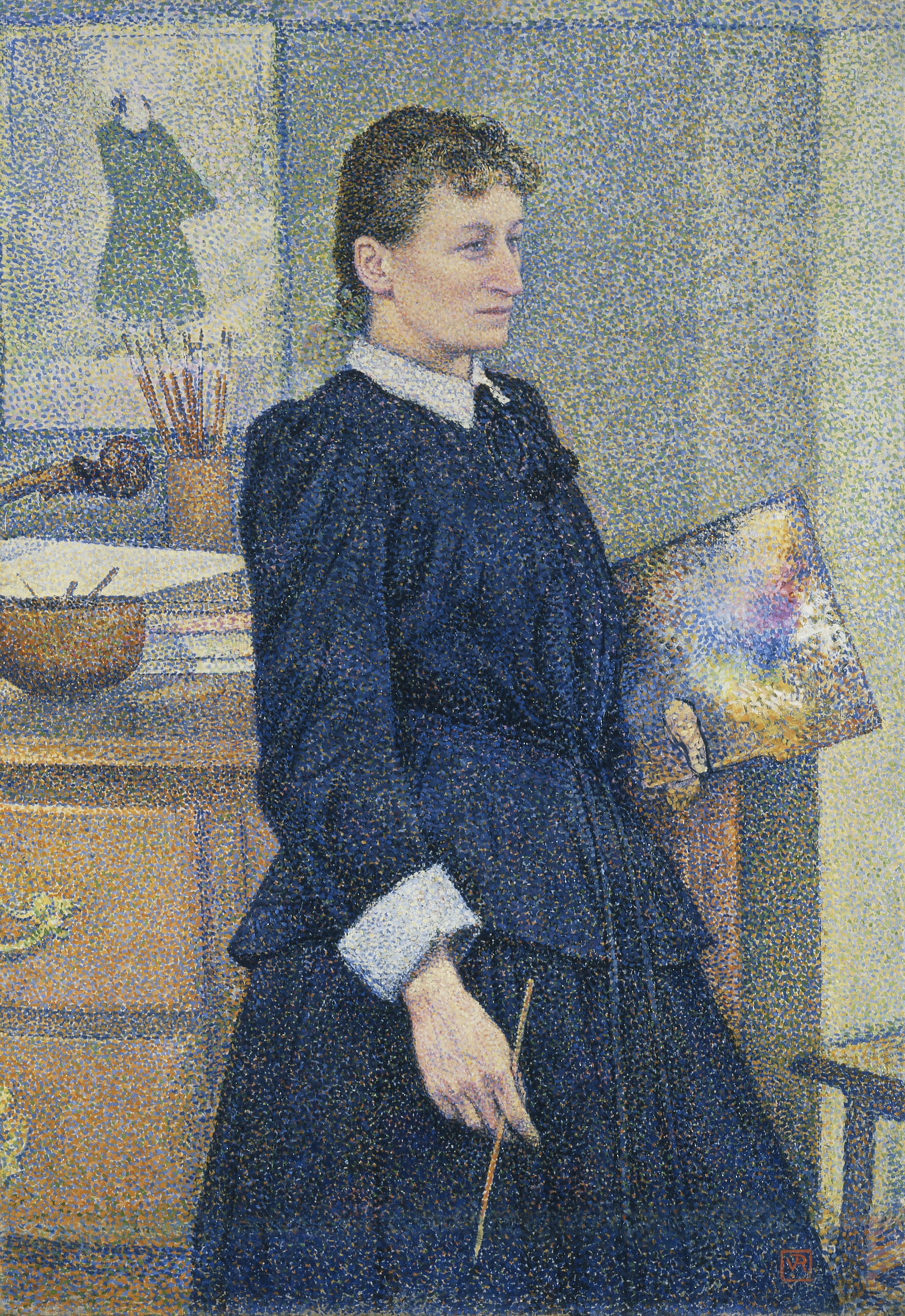

One painting in the exhibition which will be of special interest to Van Gogh aficionados is a portrait of the painter Anna Boch, who is best known for buying the only identified painting by Van Gogh to be sold during his lifetime.

On loan from the museum in Springfield, Massachusetts, the portrait of Boch was painted by the Belgian artist Théo van Rysselberghe. Boch herself painted in a Neo-Impressionist style, and she is represented in the London show by two paintings, including an evocative image of a house at dusk, Evening (1891), which is still owned by her family.

Théo van Rysselberghe’s Portrait of Anna Boch (around 1892)

Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, MA