The artist Emma Stebbins (1815-82) should be more famous than she is. After all, she created an iconic monument—the angel-topped Bethesda Fountain in New York’s Central Park. But with the opening of the new exhibition Carving Out History at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York—and a 256-page book detailing the artist’s life and work—her name is about to become better-known.

The Heckscher curator Karli Wurzelbacher and her staff—together with outside scholars, artists and critics—have spent more than five years planning a comprehensive show establishing Stebbins among the canon of greats in 19th-century Neo-Classical sculpture. Displaying 14 marble sculptures collected from around the world, Carving Out History is the first-ever exhibition dedicated solely to Stebbins’s oeuvre.

The Heckscher was not only the first museum to acquire Stebbins’s work but, for many decades, the only one to do so. Wurzelbacher, intrigued by this fact, wrote an article in 2021 that led to a descendant of the artist contacting the museum, saying there was a lot of art Stebbins made that the world had not yet seen. An exhibition dedicated to the prolific creator’s body of work, along with details of her life, began to take shape. Wurzelbacher travelled to Oregon, Rome, Belfast and elsewhere to collect precious pieces from Stebbins’s career for the show.

Stebbins’s sculptures explore the topics of gender and sexuality, ecology and industry, public health and healing, clean water and the environment. “Stebbins was this under-known, unsettled figure, but the work itself was so connected to the contemporary concerns of life,” Wurzelbacher says. “She definitely defied norms, but she and [her wife, Charlotte] Cushman were not outsiders or outliers [where they lived in Rome]. They were at the heart of the expatriate [community], the ultimate insiders. The rules were so different, and they were working within them and stretching conventions, socially and within Neo-Classical art.”

Emma Stebbins’s Charlotte Cushman (1870) Courtesy the Heckscher Museum of Art

Stebbins transformed working-class subjects into miraculous marble sculptures—a medium historically reserved for gods, mythological figures and the elite. Her attention to detail is exemplified by her unique choices, awakening in spectators a sense of community and what we owe to each other.

“Artists almost always depict the wings of angels,” the playwright Tony Kushner writes in the exhibition catalogue for Carving Out History, “with the leading edge of the wing and primary feathers pointing vertically. The wings of Stebbins’s angel [on the Bethesda Fountain] are horizontal. They lead the eye not upwards but outwards, not heavenwards but level with our earthbound surroundings. These wings are not annunciatory or admonitory exclamation marks, telling us to drop to our knees before a sovereign power. The Bethesda angel’s horizontal wings gesture laterally towards expanded vision; they’re a welcoming embrace.”

The Bethesda Fountain (1873) was meant to symbolise the “blessed gift of pure and wholesome water” after a cholera outbreak in 1832, which had led to the untimely deaths of members of the Stebbins family. In addition to evoking conversations about public health, the fountain has often been a site of community refuge in counterculture and youth movements. It has taken on special meaning for LGBTQ+ communities in particular—in part, through Kushner’s award-winning play Angels in America, which features the fountain prominently in its storytelling.

Carving Out History takes care to explicitly name and show the intricacies of Stebbins’s social network with other women, artists and friends—including the sculptors Harriet Hosmer and Anne Whitney—who became her chosen family and made her career possible. Stebbins and Cushman, a Shakespearean actress, frequently hosted salons and prioritised networking at their home in Rome. The relationships Stebbins maintained there “shaped her life and work, especially during her active years as one of the first generation of women who went abroad to pursue sculpture professionally”, notes the exhibition catalogue.

Emma Stebbins’s The Lotus Eater (1863) Courtesy the Heckscher Museum of Art

Though Stebbins eventually had to stop working in order to take care of her wife, who suffered from breast cancer, she accomplished much in her years as an artist. Her sculpture The Lotus Eater (1863) was the first male nude made by a female American artist. Later, Stebbins became the first woman to earn a public sculpture commission from the City of New York for the Bethesda Fountain. Several of her works would go on to live in the homes of prominent queer couples.

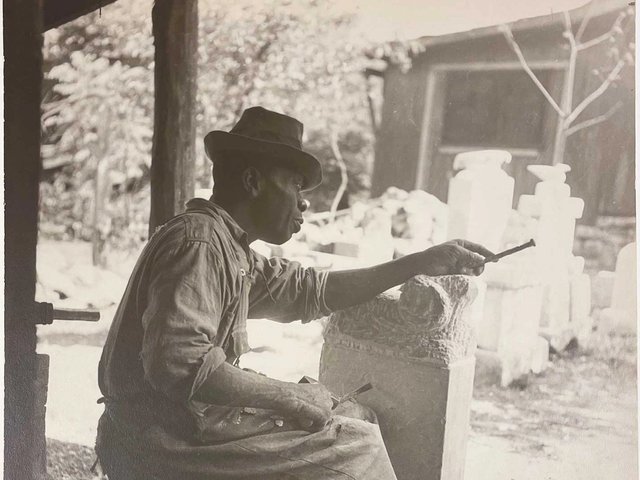

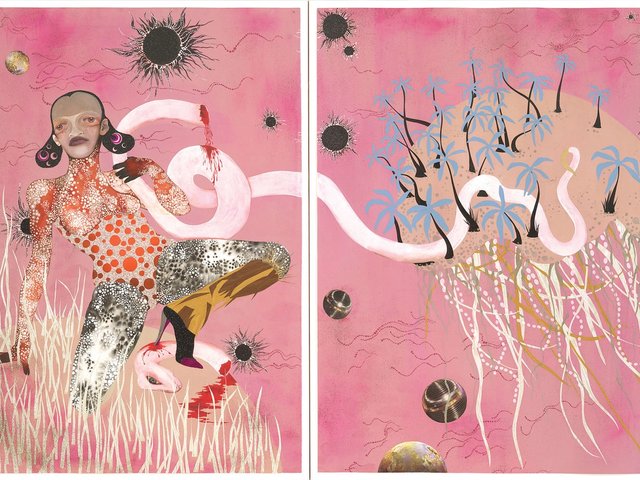

Carving Out History features a few sculptures that have not been seen in more than a century (and were thought to be lost), alongside archival documents and photographs. The show also includes works by contemporary artists like Martha Edelheit, Patricia Cronin and Ricky Flores—whose 1983 photograph shows the Bethesda Fountain at the heart of the annual Puerto Rican Day Parade.

Many of Stebbins’s sculptures have been newly conserved and photographed for the first time in preparation for the exhibition. With its archival materials, Carving Out History offers an unprecedented opportunity to understand Stebbins’s range, motivations and impact.

“The meaning of her work has been renewed and expanded across this entire 150 years,” Wurzelbacher says. “It’s remarkable to see it come to life in this way.”

- Emma Stebbins: Carving Out History, Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York, 28 September-15 March 2026