Christie’s will sell three early Lucian Freud paintings from the same collection in its London evening sale on 15 October, with a combined estimate of £13m to £20m.

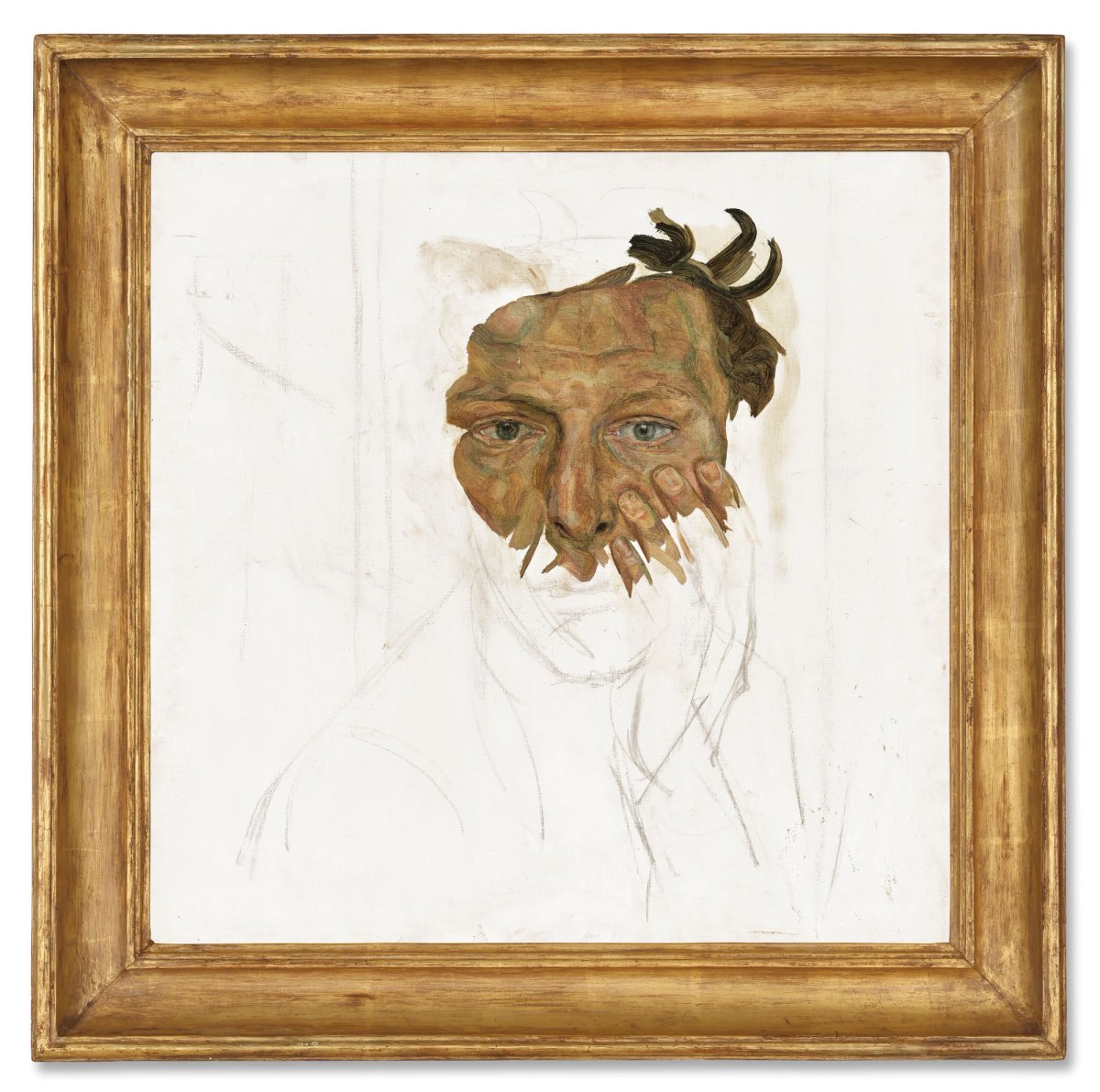

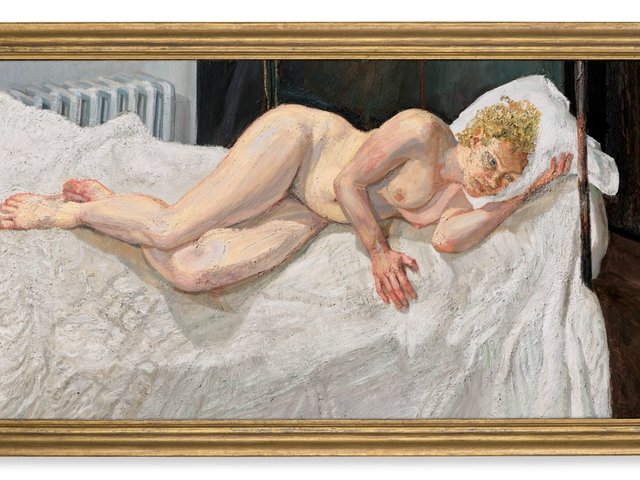

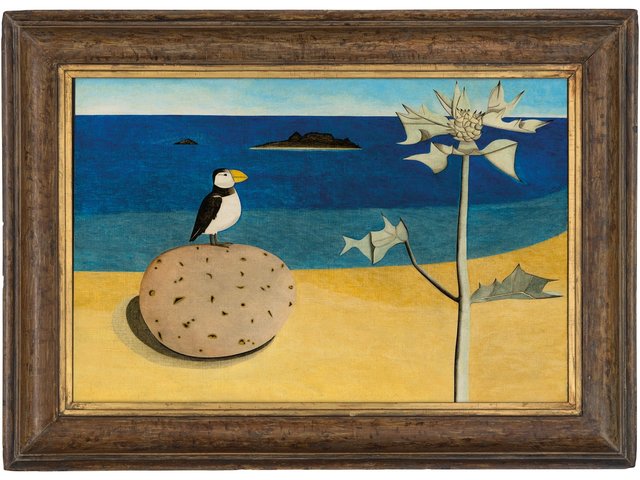

The works show Freud’s style evolving over three decades: from the crystalline tension of the wartime Woman with a Tulip (1944), to Self-portrait Fragment (around 1956), painted as his marriage was dissolving, to the bolder fluency of Sleeping Head (1961–71).

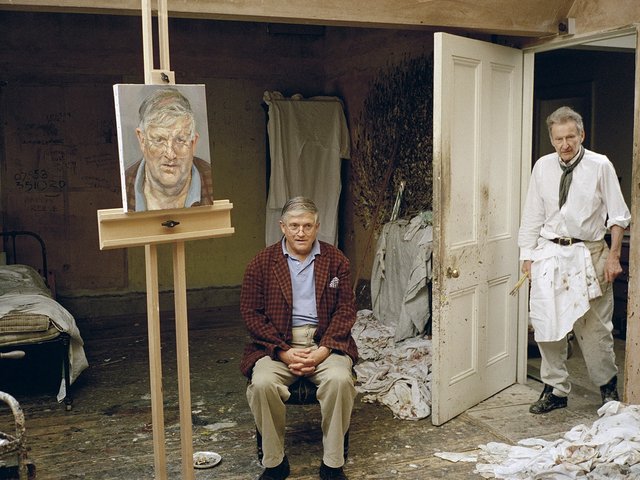

The paintings have all been in the same private collection for many years and, although Christie’s declines to comment on the identity of the owner, the works are currently in free circulation in the UK. They have all been exhibited widely in major shows such as the touring exhibition Lucian Freud: Paintings (1987–88), which travelled to Washington, Paris, London and Berlin, his Kunsthistorisches Museum retrospective in Vienna in 2013, and Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, at the National Gallery, London and the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, in 2022-23.

Lucian Freud, Woman with a Tulip (1944)

Courtesy Christie's Images 2025

Woman with a Tulip (1944, est. £3m-£5m) depicts Lorna Wishart, whom Freud described as "the first person who meant something to me". Wishart, the famously beautiful youngest Garman sister and the aunt of Kitty Garman, who later became Freud’s wife, also appears in another of Freud’s works, Woman with a Daffodil (1945), now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Precisely painted with the sable brushes Freud favoured in his youth, this icon-like painting was exhibited in Freud’s first solo show at the Lefevre Gallery in 1944 and, in its stillness, intensity and use of iconography, is clearly a stylistic precursor to well-known paintings such as Girl with a Kitten (1947) and Girl with Roses (1947-48). It has been in the seller’s collection since it was bought from Freud’s dealer and agent James Kirkman in 1995.

“This picture feels quite devotional, as opposed the later painting of Lorna [in Moma], which shows how the relationship had soured,” says Katharine Arnold, the vice-chairman 20th/21st century art, and head of post-war and contemporary art, Europe at Christie’s.

Freud had moved on by the time he painted Self-portrait Fragment (around 1956, est. £8m-£12m), an equally intense but larger work painted in the non finito tradition, which was first shown at London’s Marlborough Gallery in 1968, where the vendor bought it (the Kunsthistorisches Museum retrospective in 2013 was the first time it was seen in public for 45 years). In the mid-1950s, Freud had just transitioned to using thicker, hog’s hair brushes and was spending a lot of time with Francis Bacon—in the 2022-23 National Gallery exhibition, this work was hung next to his portrait of Bacon, painting in 1956–57.

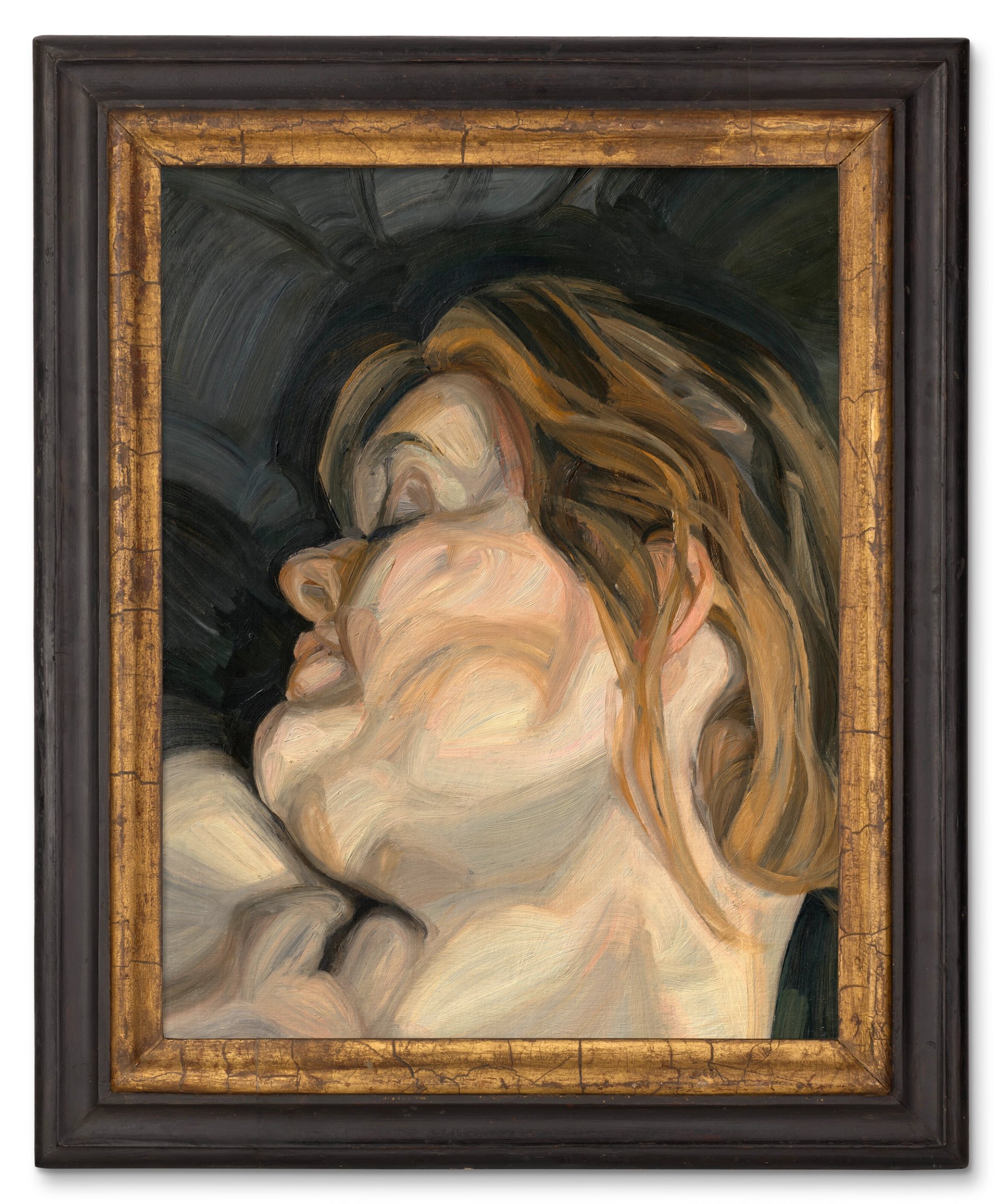

Lucian Freud, Sleeping Head (1961-71)

Courtesy Christie's Images 2025

“Already by 1956, you’re looking at an older man—Freud is in his 30s and he is fascinated with how paint could change, how it could begin to relax,” Arnold says. “At this point, Bacon has an important influence over Freud’s practice and it is with some encouragement from Bacon that Freud decides to loosen up his brushwork. There’s a story that, in the early period, Freud said he would sometimes see the outline of his eye on the canvas because he was staring so hard. But by 1956-7 he has started to loosen up.” She adds: “Freud is not looking at us in this picture, he is looking at himself. His relationship with his then wife Caroline Blackwood is changing, he is not in the first flush of love.”

The brushstrokes get thicker and more expressive still in Sleeping Head (1961–71, est. £2m-£3m), the only one of the trio to have previously appeared at auction—at Christie’s London in 1971, when it was sold by the 5th Marquis of Dufferin and Ava, Sheridan Dufferin, Blackwood’s brother. First shown at Marlborough Gallery in 1963, the tightly cropped work depicts a young woman, who met Freud in a Soho bar, dozing on the oft-depicted shabby leather sofa in his Paddington studio.

“This painting marks another transition in technique again,” Arnold says. “At this point he has just come back from Greece and he has a brief relationship with this woman. We don’t know who she is, but he is painting in a very free, confident way. We don’t know if that’s a reflection of his personal life—he’s no longer married—but he’s now stepping into a very fluent, easy painting style. So, when you look at all three works together, you have this arc of painting technique.”

On the market for Freud’s work, Arnold says: “There’s a high degree of curiosity in the early works, the reason being that after 1958 the technique has changed so there’s only a discreet moment in time when these works were being made, therefore they are rare, especially as a lot of the great early paintings are in public institutions.” She adds: “I think the buyers of these early works might just as easily be the buyer of a 1932 Picasso—they’re not necessarily the sort of person who would buy a British figurative painter.” The sitter also plays a role in a works appeal and, Arnold adds, “a self-portrait is always a particularly interesting insight into a painter, so they tend to be the most prized—we have collectors who only buy self-portraits.”

As for geographical demand, Arnold says: “Over the past year, we’ve sold a major painting to North America, two to Asia, we’ve had deep European bidding, UK buyers. So, it’s universal.”

The paintings have been guaranteed to sell by Christie’s.