Friedrich I of Baden-Württemberg (1754-1816), in common with many monarchs of his era, decorated his palaces to broadcast power. After allying with Napoleon and upgrading his rank from duke to king, he communicated his rise in status with an update of his summer residence, Ludwigsburg Palace, one of Germany’s biggest Baroque castles.

Four prized rooms among Friedrich’s apartments are expected to reopen to the public in 2026 after substantial restoration, including the unusually complete drapery bedchamber. After Napoleon’s 1798-1801 Egyptian campaign, his publications of its scholarly findings, including engravings of Egyptian styles, were widely disseminated. A fashion for Egyptian styles and military camp furnishings swept Europe and inspired Friedrich’s architect, Nikolaus Friedrich von Thouret.

“This is probably the only palace in Europe to have a drapery room remaining to this extent of completeness, including fabric, trimmings, and furnishings to match,” says Anu-Susanna Ventelä, a textile conservator at the State Palaces and Gardens (SPG) of Baden-Württemberg. Exposed to years of soil, dust, sunlight, pollution and even insect retardants, the silks, originally turquoise and now a faded blue-green, needed cleaning, she says.

More rooms than days in the year

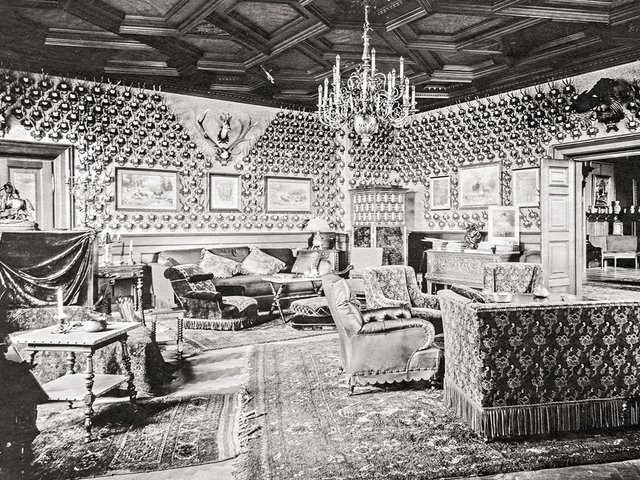

Sometimes described as the “Versailles of Swabia”, Ludwigsburg Palace is located near Stuttgart in south-west Germany. Comprising 452 rooms, it displays a range of interior styles added by Württemberg’s dukes, from early 1700s Baroque through 1760-70s Rococo to Friedrich’s revisions guided by Thouret, who had trained in Italy and France. Napoleon visited the palace in October 1805 and was received with full honours. Today, Ludwigsburg hosts concerts, weddings and festivals. Last year, it welcomed more than 260,000 visitors.

The project to restore the drapery bedchamber is part of a larger revamp of 35 rooms, which began in 2016 and is funded by the State of Baden-Württemberg. The SPG is responsible for the interior work. When The Art Newspaper visited in May, huge chandeliers on the floor in the Marble Hall resembled giant cakes, protected by plastic; floors and ceilings were covered in protective panels; and a restorer worked on an oak leaf-patterned wood moulding in the Audience Room, where Friedrich’s red velvet throne (1806) will return after cleaning.

Elena Hahn, the SPG conservator in charge of the project, explains that a main goal is to “bring the rooms back to their historical furnishings, including layout”.

Furniture hide and seek

To achieve that with around 2,000 wall hangings, furnishings, paintings, porcelain objects and clocks, SPG consulted old inventory books. Few changes were made in the furnishings after Friedrich died in 1816, so “unusually, about 80%-90% of the items are still here and identifiable”, Hahn says. But many had to be tracked down, and repositioning was not obvious. If the inventory assigned an armchair with green fabric and bronzes to a particular location, that chair had to be found. The sequence of paintings on the walls was decoded when researchers realised that the inventories listed works from top to bottom, or left to right.

The original blue silk textiles in the 1811 bedchamber will be a highlight. Their vast yardage—330 sq. m of fabric, 165m of galloons (fabric borders), and over 6,000 tassels—created a huge logistical challenge. The large wall panels were brittle and fragile after years of door friction, damage and simply bearing their own weight. Each was moved by four people using two tubes at either side to roll them up.

Damage was identified and mapped to locate soil, holes, seam openings and improper earlier mending. Three different local vendors are involved in cleaning the fabrics, because no single vendor has premises large enough for the whole job.

‘Fat Friedrich’s’ superking bed

The bed is 2.2m long to accommodate the king’s considerable size; he is said to have been more than 2m (six foot six inches) tall and was dubbed “der dicke Friedrich”, or Fat Friedrich. (Napoleon is alleged to have said that he was living evidence of how far human skin could stretch.) The bed textiles, too fragile to be removed from their mountings high on the baldachin, have stayed in place, where restorers will stand on scaffolding to clean them.

“The goal is not to make the textiles new, but to reinforce what has been damaged,” Ventelä says. To remove dust, restorers are using contact-free vacuum cleaners which blow air above the fragile surfaces while simultaneously sucking up debris, avoiding potential damage from bristles.

New fabric panels of lightweight silk will be hung on the walls behind the originals to provide a supportive backing. Couching stitches placed at intervals will tack the linings to the originals to help carry some of the older fabric’s weight. Where holes appear, the illusion of patches will be created by carefully dyeing the backing to match the surrounding fabric, as sewn-on patches would be too heavy for the originals to bear.

An additional aim of restoring the furnishings is to let visitors see how the king used the rooms at the time, Hahn says. In the Conference Room, for example, 16 items of yellow seating furniture will be returned; the room will look “quite full, like rooms were at the time”, she says. It is almost as though Friedrich could return to find every stitch and chair in place.