1. The museum once captured a mermaid

The museum’s specimen is said to have been “caught” in Japan just after 1700. Of course, it is a fake: part of a stuffed monkey, with a fish tail and fish jaw, complete with teeth. The mermaid has a royal provenance, since it was given to Prince Arthur, the seventh child of Queen Victoria, on a visit to Tokyo in 1906 when he awarded the emperor with the Order of the Garter. The mermaid (or merman, since its gender is unclear) is on display in the Enlightenment Gallery.

Mike (1920-29), faithful servant to the Egyptologist Wallis Budge © The Trustees of the British Museum

2. It was once home to Mike, the fearless mouse catcher

Mike (1909-29) is the most celebrated of the museum’s cats. His mother deposited him as a tiny kitten at the feet of the distinguished Egyptologist Wallis Budge, who became his lifelong friend. Mike remained faithful to Budge, allowing himself to be stroked, but was aggressive to museum visitors who approached him. He certainly struck fear into mice and pigeons, helping to keep the museum clear of these unwelcome creatures. Mike was honoured on his death with an obituary in London’s Evening Standard and America’s Time magazine. He was buried beneath a gravestone near the entrance gate, but sadly this has now disappeared.

Stuffed giraffes were in residence at Montagu House from the 1770s © The Trustees of the British Museum

3. It hosted Britain’s first giraffes

The first giraffes to arrive in London were not live, but stuffed. The first, a young specimen, came in the 1770s and from the 1810s it was dramatically displayed with two others at the top of the stairs of Montagu House, where the museum was then based. The British Museum then also covered natural history, which was later hived off to a separate institution in South Kensington, which opened in 1881. Sadly, the stuffed giraffes have been lost. A Natural History Museum curator told us last month that because of “poor environmental conditions” at the British Museum in the 19th century, quite a number of specimens were damaged or disposed of.

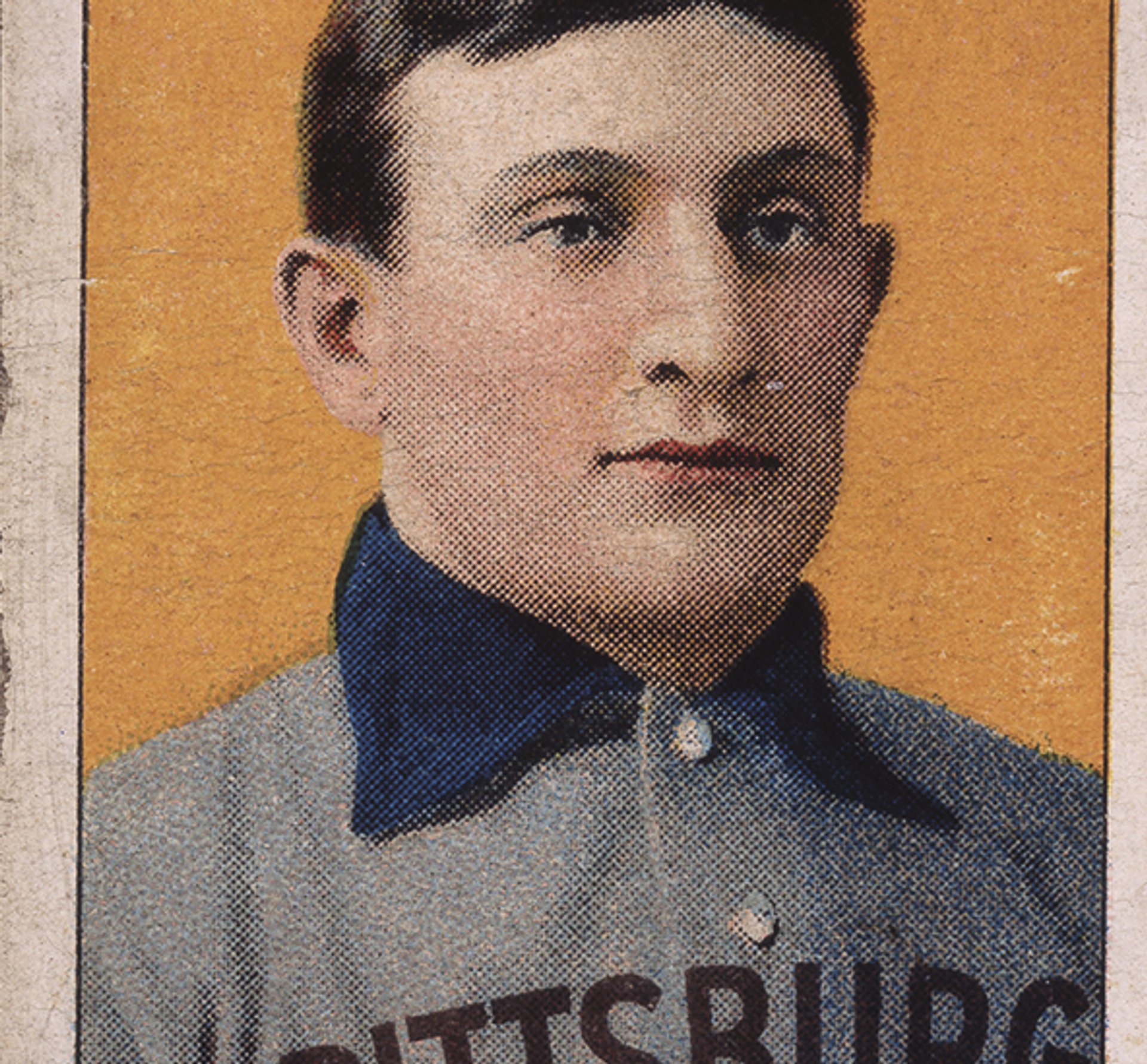

A 1909-11 cigarette card featuring American baseball player Honus Wagner is the only one displayed from the museum's 1.5 million-strong collection © The Trustees of the British Museum

4. Over 1.5m cigarette cards are in storage there

As recently as 2006 the museum accepted the last batch of late 19th- and early 20th-century cigarette cards, small collectable items that were inserted in packets and sometimes aimed at children. This collection was assembled by Edward Wharton-Tigar, a Second World War spy who carried out sabotage operations in Tangier. He estimated the size of his collection at 1.5 million cards. With this quantity, the museum has been unable to catalogue individual cards, making it difficult for any researcher to ask to see a specific one (although all are available). Only a single card has ever been exhibited, an extremely rare 1909-11 one of the American baseball player Honus Wagner. Another example sold for $3.1m in 2016.

5. Until 2005, dangerous erotica could be found in the Secretum

Until the 20th century objects and images that were regarded as erotic were often stored in the Secretum, which consisted of locked cabinets behind the scenes. Access to the contents was restricted to scholars and the clergy, who had to apply in writing to the director. The last acquisition was in 1953, when a condom was discovered in the library’s collection which had been used as a bookmark in an 1783 edition of A Guide to Health, Beauty, Riches, and Honour. Although objects were gradually moved out of the Secretum and integrated into the relevant collection, it still existed up until 2005.

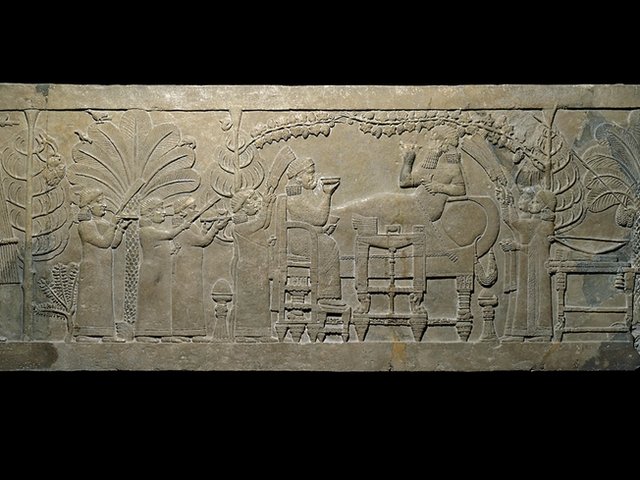

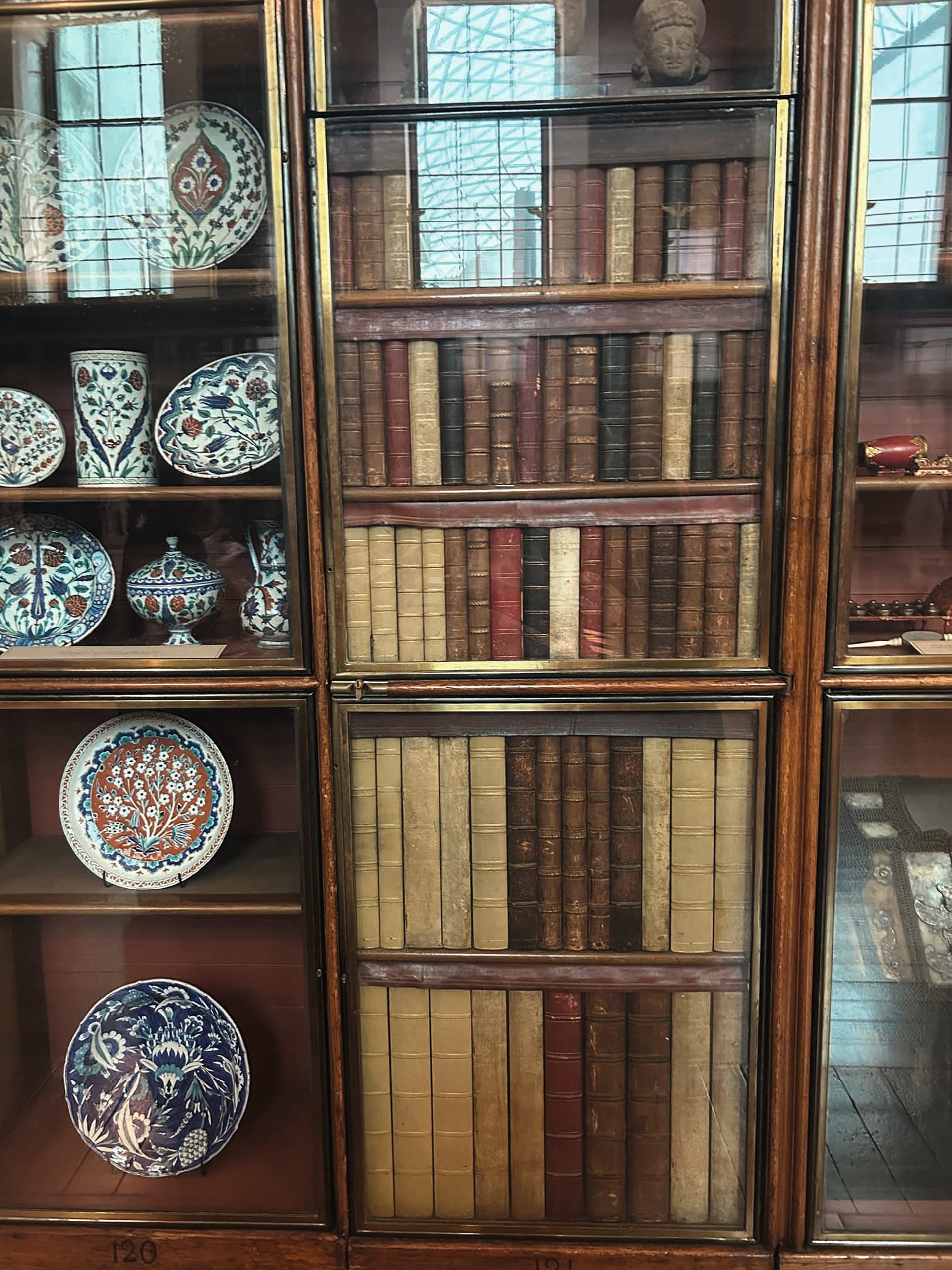

The Enlightenment Gallery's hidden door was available to fugitive director, Anthony Panizzi The Art Newspaper

6. A former director had a fake door to escape through

Behind a “bookcase” in the Enlightenment Gallery is a hidden door, which in the 1850s led to the office of the director, Anthony Panizzi. He had fled from Italy in 1822 and was then condemned to death in absentia on subversion charges and membership of a secret revolutionary movement, the Carbonari. In London he worked at the British Museum, rising to become director. At the museum he needed somewhere to hide, since he feared he might be pursued by the Italian authorities. The glass-covered door, with its fake book spines, is still there (in the north-east corner of the room), although few visitors notice it. It remains in working order, provided you have the key. Panizzi’s other architectural innovation was to sketch the design for the Round Reading Room.

7. Its basements were once rather different

Many of the museum’s storerooms are in the basements below the main part of the building, dating back to the 19th century. David Wilson, the director from 1977 to 1992, described his early underground visits as a “revelation”, with “far too much smoking taking place and a number of unofficial canteens”. In rooms “filthy with the dust of ages” he discovered a freelance cycle-repair workshop, an ancient fish fryer (subsequently despatched to the Science Museum) and, on one occasion, a man performing yoga. Following Wilson’s 1970s “blitz”, the basements were cleared, cleaned and put into “proper use”.

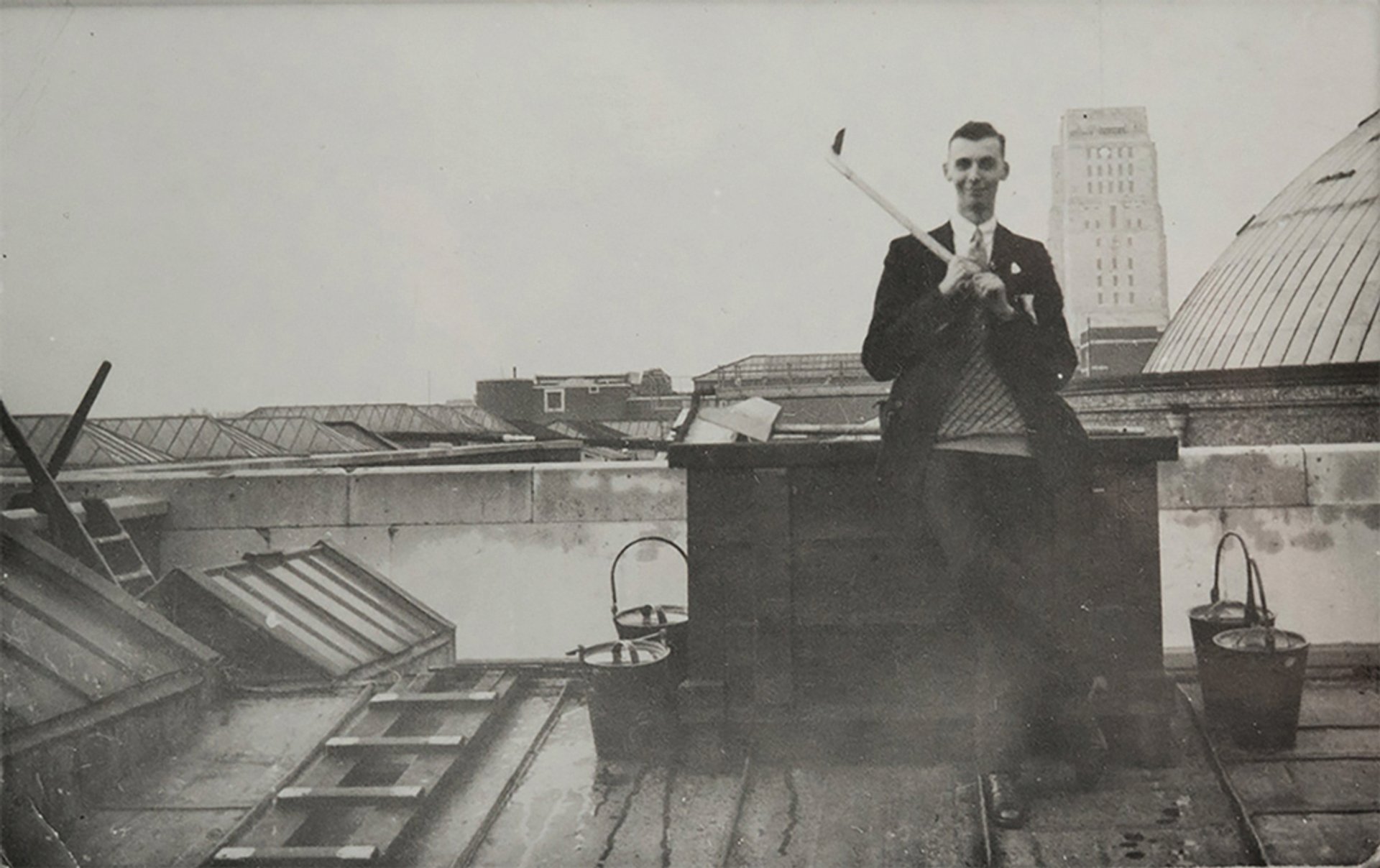

Good sport: sticks resembling golf clubs were used to flick unexploded bombs off the museum's roof during the Second World War © The Trustees of the British Museum

8. It was protected from German bombs with the help of ‘golf clubs’

During the Second World War warders were stationed on the museum’s roof to deal with Luftwaffe bombs. Equipped with sticks that resembled golf clubs, their job was to deal with unexploded bombs—by pushing them into a bucket of sand or knocking them off the roof. The museum was bombed several times between September 1940 and May 1941. On the last occasion the south west of the building was hit by dozens of incendiary bombs, destroying 250,000 books.

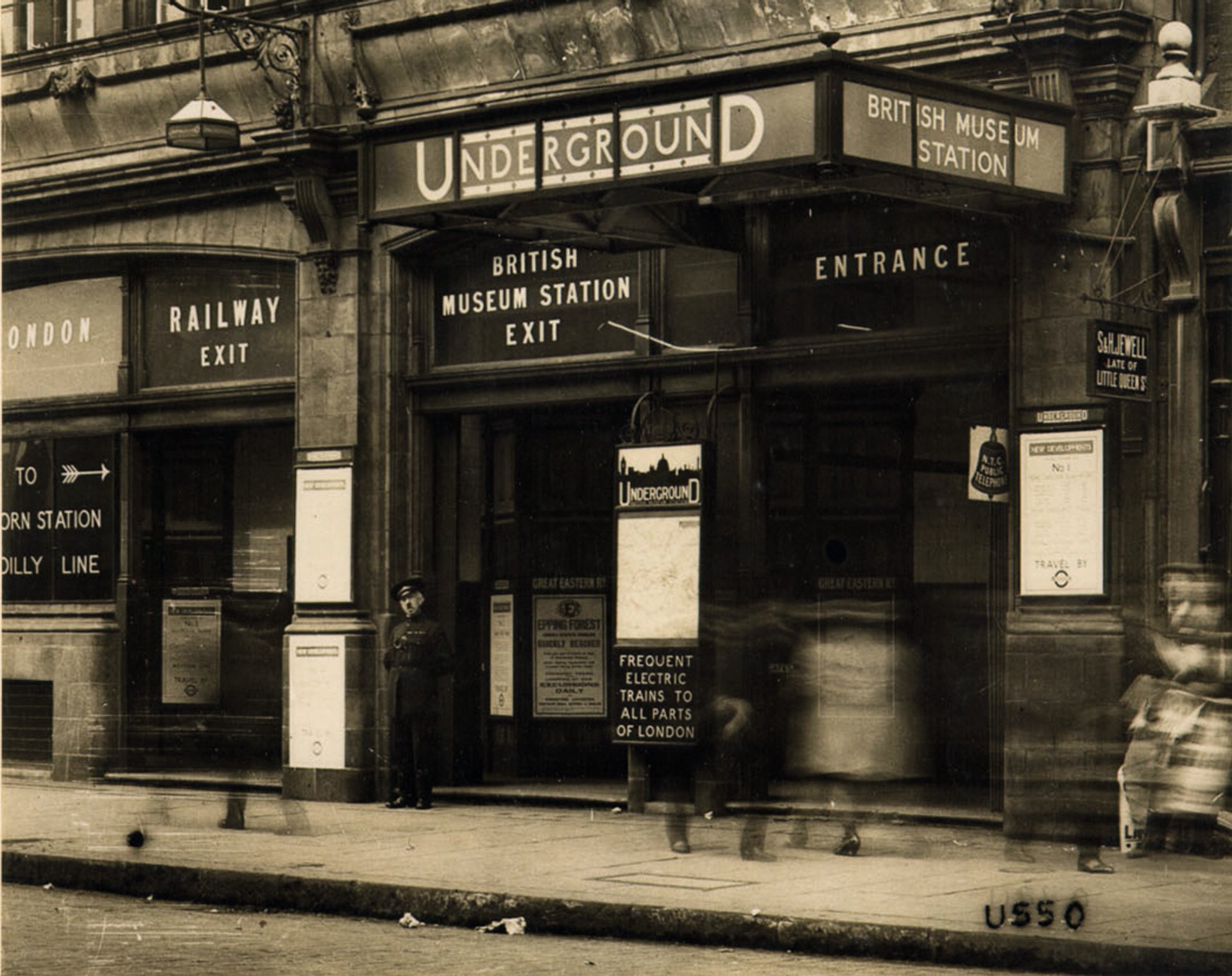

The British Museum's underground station ferried visitors from 1900-33 © London Transport Museum collection

9. It once had its very own underground station

The British Museum underground station opened in 1900, on the Central line. Then in 1933, with the inauguration of nearby Holborn station, on the Piccadilly line, the museum’s station was closed and passengers were diverted to the new facility. The British Museum station then served as a secret military command post until the 1960s. The surface building was eventually demolished in 1989, making way for an office block in High Holborn. However, the tube system continued to serve the museum in a different way. During the Second World War Aldwych station, a short hop away from Holborn, was used to secretly store some of the museum’s greatest treasures on platforms deep below the ground.

10. There are objects even curators are not permitted to see

The British Museum owns 11 tabots, which are sacred tablets that once belonged to Ethiopian Christian churches. Symbolically representing the Ark of the Covenant, they were looted by British troops during the siege of Maqdala (pictured above) in 1868. The orthodox church believes that tabots should never be seen by anyone other than their own clergy. The museum now keeps them in a sealed basement store, where they are only accessible to Ethiopian clerics. Even the museum’s curators and conservators are unable to view them. Despite calls for the tabots’ return, the museum argues that it is legally unable to deaccession, only to make loans.