The first comprehensive exhibition of Van Gogh’s portraits of the postman Joseph Roulin and his family has just arrived in Amsterdam, following its presentation in America. Van Gogh and the Roulins: Together Again at Last opens today (3 October) at the Van Gogh Museum, and runs until 11 January 2026. At Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts it attracted 280,000 visitors—and it's likely to see even more in Amsterdam.

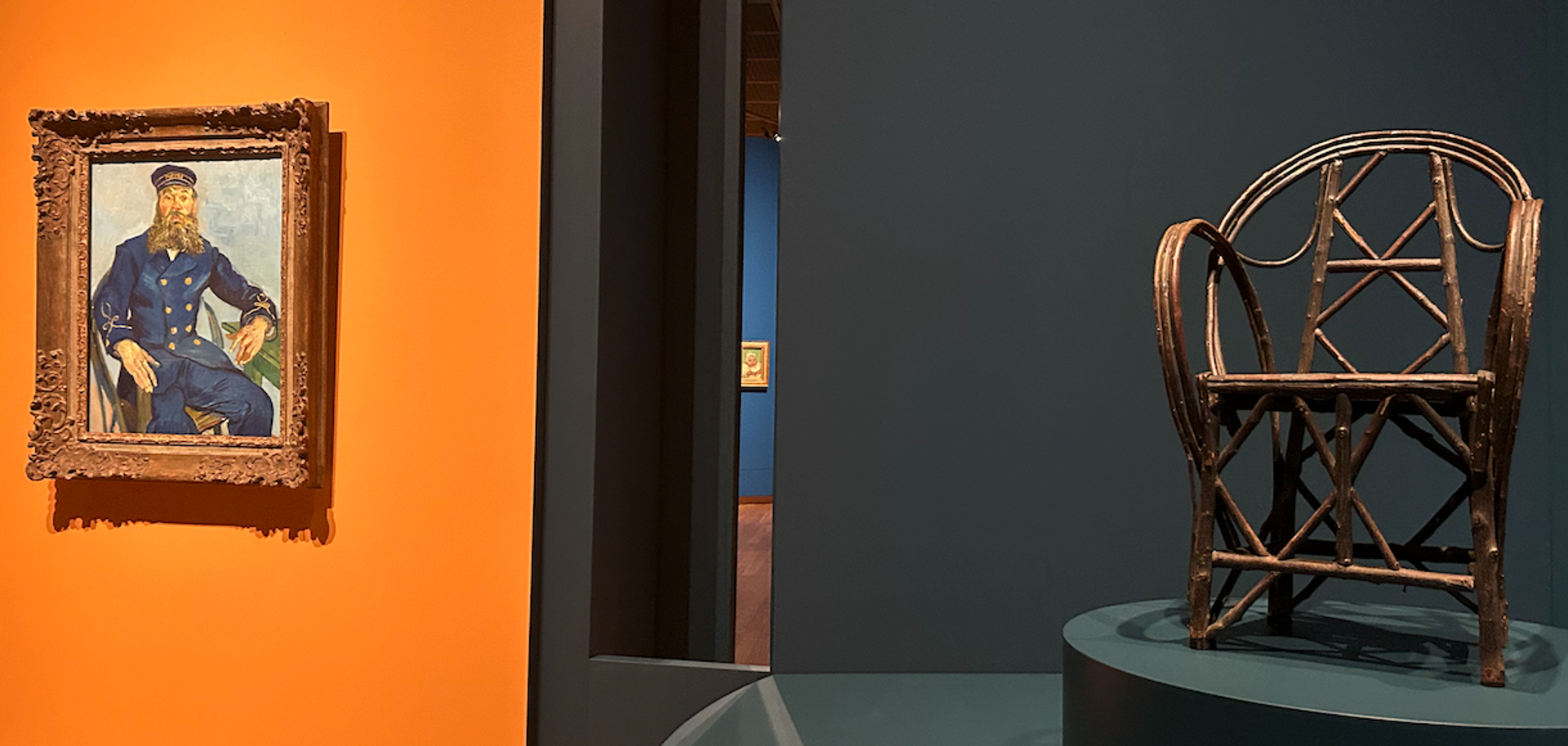

Van Gogh’s Postman Joseph Roulin and the actual chair, presented in the exhibition Van Gogh and the Roulins: Together Again at Last (until 11 January 2026)

The painting is from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the chair at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (photograph The Art Newspaper)

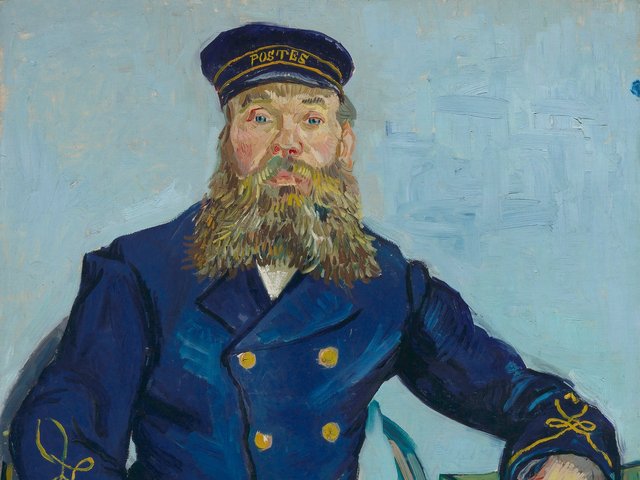

The centrepiece of the Amsterdam show is Van Gogh’s first portrait of the postman, on loan from Boston. It was painted in Arles at the very end of July 1888. At the time, Vincent lightheartedly complained to his brother Theo that although he had not needed to pay Roulin to pose, it would have been cheaper to have given him a few francs. “The chap, not accepting money, was more expensive, eating, drinking with me,” he wrote. Vincent and Roulin quickly bonded, frequently patronising the Café de la Gare.

Frans Hals’ The Merry Drinker (1628-30) and Van Gogh’s Postman Joseph Roulin (July-August 1888)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

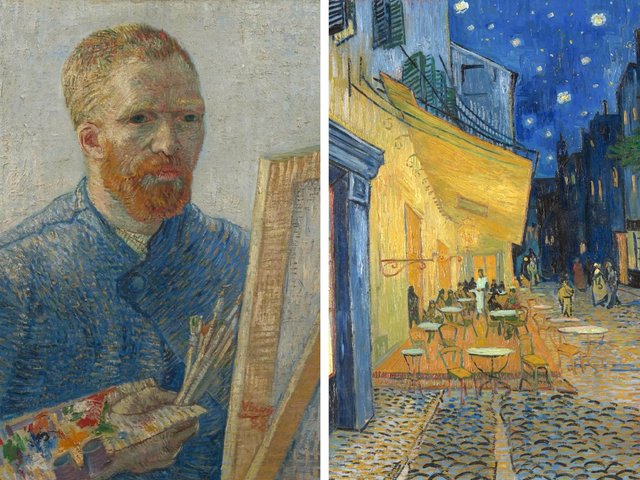

In his portrayal of the postman, Van Gogh was partly inspired by The Merry Drinker (1628-30), by the Dutch 17th-century artist Frans Hals. On the very day that Roulin was sitting for him, Van Gogh wrote admiringly about Hals’ “tipsy drinker” to his friend Emile Bernard. On an earlier occasion Van Gogh described the colour of the face of the Hals imbiber as “a daring and masterly bronze, like wine-red”.

In the Van Gogh painted portrait there are clear parallels with the Hals—in the sitters’ outward gaze, frontal chests and foreshortened left arms. Both portraits are also loosely painted. The Merry Drinker made a strong impression on Van Gogh on a visit to the Rijksmuseum in 1885 and he may also have known it from reproductions.

In Van Gogh’s three-quarter-length portrait, Roulin sits in a wicker armchair. His bulky frame fills most of the composition, with his beard fanning out below his face, creating a benign demeanour. Roulin’s dark blue uniform with golden-yellow braid and his cap emblazoned with “POSTES” proudly proclaims his profession.

Blue and yellow are complementary colours, which Van Gogh loved to use. As so often in Van Gogh’s work, the arms and hands appear to be clumsy. Roulin was then aged 47 (he died at in 1903, at 62).

Joseph Roulin, aged 61 (1902)

In a drawing made after the painting, Van Gogh included a glass (as in the Hals), resting just beside the sitter. Although it was drawn to inform his brother Theo about the work, Vincent omitted the glass in the painting. Perhaps in the drawing for Theo he was simply emphasising the postman’s love of drink.

A drawing of the Postman Joseph Roulin (August 1888). The drawing was exhibited in Boston, but not in Amsterdam

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

At Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum the Boston painting is accompanied by the original chair on which Roulin posed on 31 July 1888. The chair had been bought by Van Gogh for the Yellow House, where he lived in Arles.

When the artist moved to the asylum in May 1889 he left his furniture with his friends Joseph and Marie Ginoux, who ran the nearby Café de la Gare. On Marie’s death the chair passed to her niece and much later, in 1969, it was acquired by Theo’s son Vincent for the Van Gogh Museum. It is exhibited for the first time since then.

As for Postman Joseph Roulin, the painting was also left with the Ginouxs. They sold it in 1897, when it was bought for a very low sum by the avant-garde Parisian dealer Ambroise Vollard. After passing through several European owners it was acquired in 1928 by the Boston lawyer Robert Treat Paine II for $48,000. Seven years later he donated it to the city’s Museum of Fine Arts.

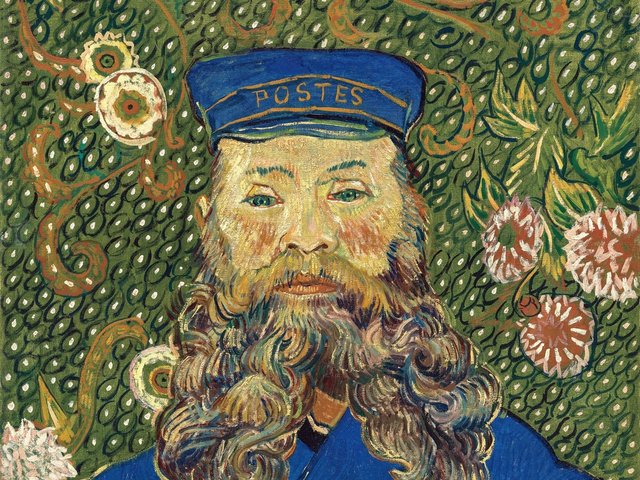

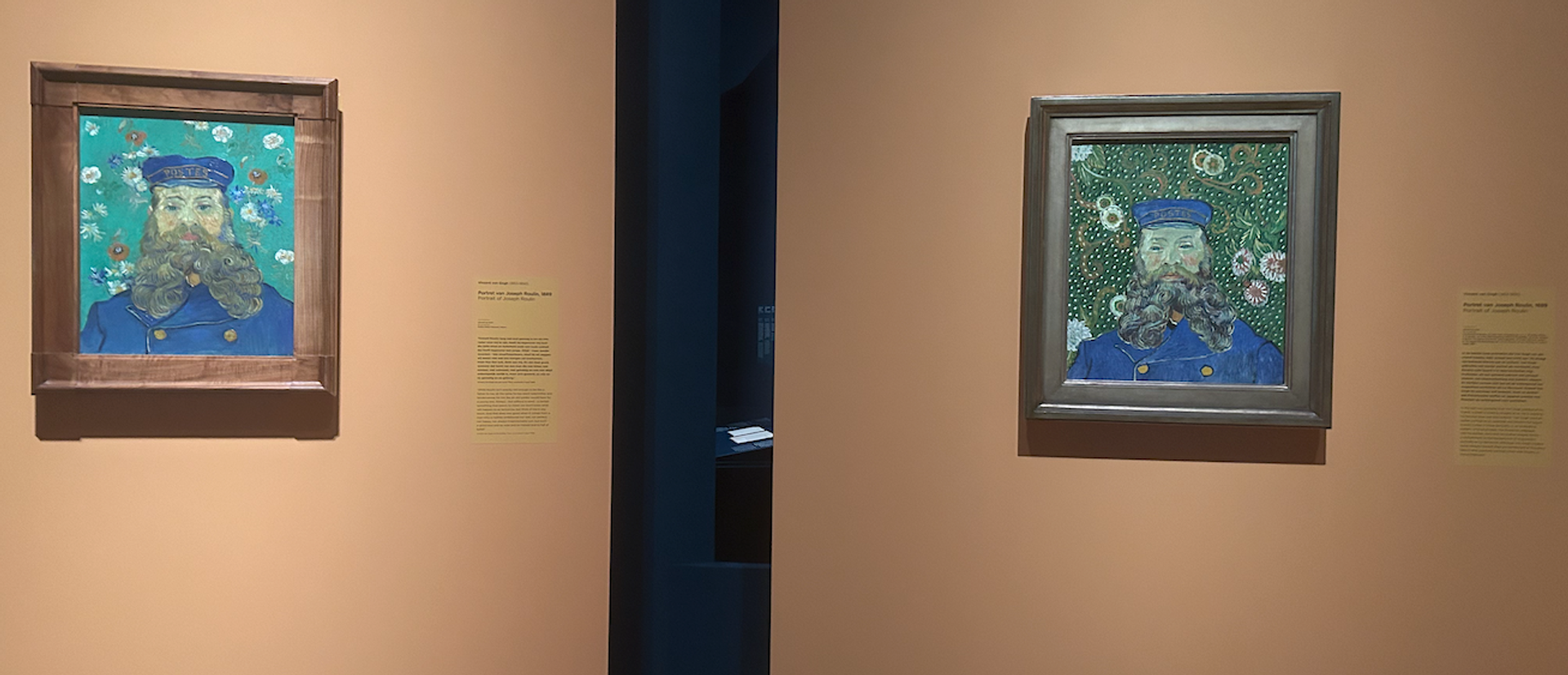

After the full-length composition, Van Gogh went on to paint five head-and-shoulders portraits of the postman. Three are in the Amsterdam exhibition, on loan from Otterlo, New York and Winterthur; the other two, in Philadelphia and Detroit, were not available.

Van Gogh’s portraits of Joseph Roulin (January-February 1889)

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo and Museum of Modern Art, New York (photograph The Art Newspaper)

Van Gogh also made a number of portraits of Joseph’s wife Augustine and their three children, Marcelle (four months), Camille (11) and Armand (17). Altogether he painted 23 portraits of the Roulin family, accounting for just over half of his Arles portraits. Fourteen have been reassembled at the Van Gogh Museum by the co-curators, Amsterdam’s Nienke Bakker and Boston’s Katie Hanson.

Van Gogh’s Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle (December 1888-April 1889), Camille Roulin (November-December 1888) and Armand Roulin (December 1888-April 1889)

Philadelphia Museum of Art; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) and Museum Folkwang, Essen

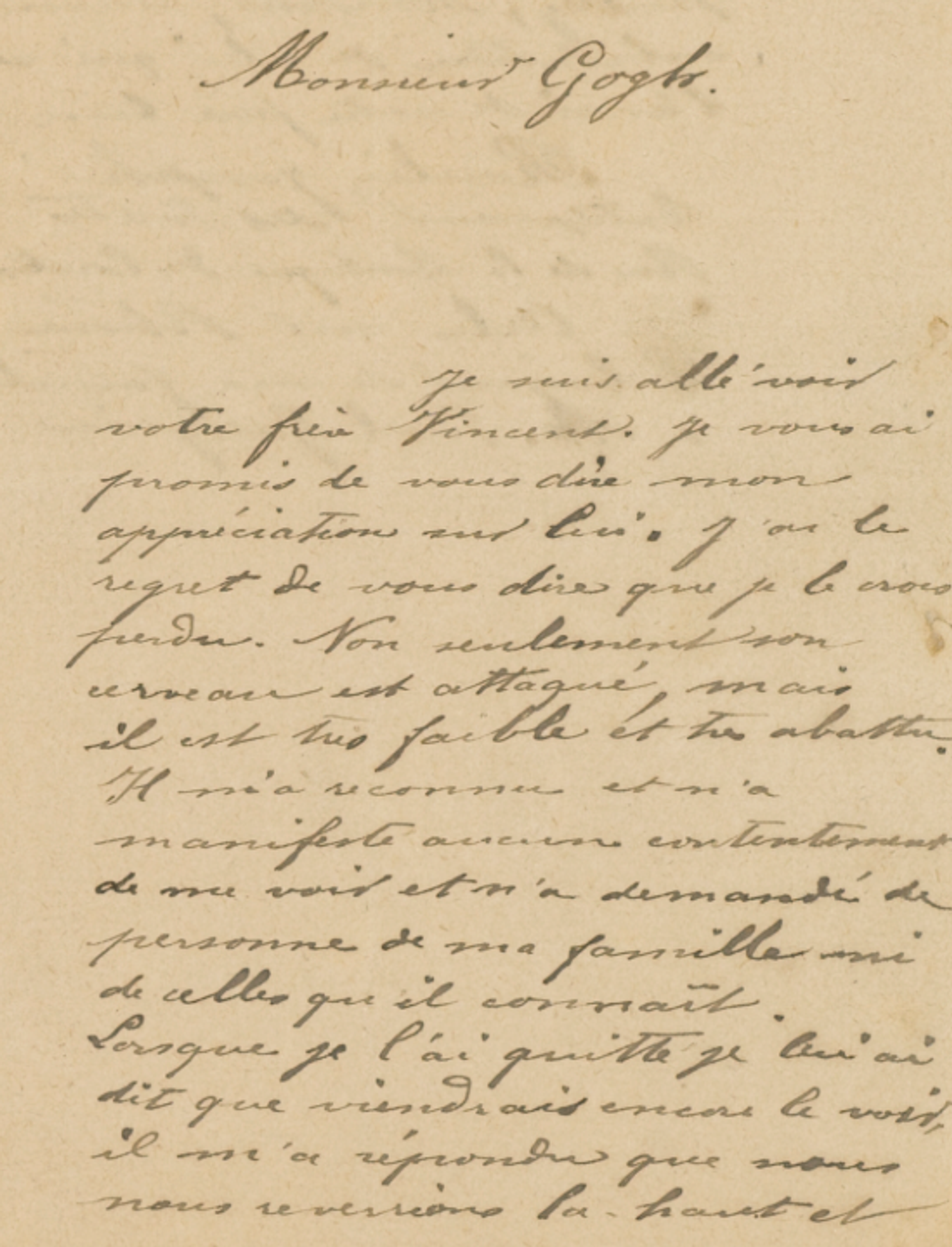

Roulin proved a loyal friend. It was he who came to help Van Gogh after he mutilated his ear in the evening of 23 December 1888. Three days later Roulin wrote to Vincent’s brother Theo, after visiting the artist in hospital warning that the patient was “lost” and “despondent”. When Roulin said goodbye, Van Gogh pessimistically told him: “We would see each other again up there [in heaven]”.

Roulin’s letter to Theo van Gogh, 26 December 1888

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Fortunately Van Gogh’s wound healed quickly and on 3 January Roulin telegraphed with the good news that he had “entirely recovered”. The originals of the ten letters sent by Roulin to Vincent's family are being shown for the first time in the Amsterdam exhibition.

On 31 July 1888 Vincent wrote to his sister Wil, telling her about his first portrait of the postman: “I much prefer to paint something like this than flowers.” However, wisely, he also immediately added: “As one can do the one and not neglect the other, I just take the opportunities as they arise.” Fortunately portraiture did not entirely take over Van Gogh’s efforts, as less than a month later he completed his four still lifes of the Sunflowers.