Of the roughly 12 million Africans who were forcibly taken to the Americas during the transatlantic slave trade, more than five million were transported to Brazil, making it home to the largest enslaved population at that time. Today, this influence on Brazilian culture—from music to religion—is unmistakable, yet remains little discussed outside the country. The relationship between Brazil and Africa, both historically and today, serves as the jump-off point for Echoes in the Present, a new section at this year’s Frieze London curated by the Nigerian art historian Jareh Das.

Across eight galleries featuring ten artists, Echoes in the Present highlights how the cultural influences between Africa and Brazil have flowed both ways, a realisation Das first made growing up in Nigeria in the 1990s. “There were references to Brazilian culture through food, people’s last names,” she says. “I then later came into an understanding of enslaved people from Yorubaland who were forcibly removed and taken to Brazil, who then returned to Nigeria as freed slaves.”

The show is part of a growing wave of exhibitions revisiting this history. In 2018, Afro-Atlantic Histories was shown in São Paulo and later across the US from 2021 to 2024, including at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. It had a particular (though not sole) focus on Brazil when looking at the histories around the African diaspora. Last year, Brazil and Africa: a shared history, featuring the work of the Brazilian artist Aline Motta, was staged on Gorée Island in Senegal, a major departure point for enslaved Africans. In 2024, Das also co-curated Catch the Invisible at Galerie Atiss Dakar in the Senegalese capital. “It was really trying to unpack the interconnectedness and geography between Brazil and the west coast of Africa,” she says, mentioning that a part of the show looked into how the connection between the two places manifested spiritually.

Building on these themes, Echoes in the Present examines how the legacy of Africans transported to Brazil continues to shape the artistic practices of Africans, Brazilians and their diasporas. Many of the artists in the show work with a range of materials, and their ties to this history manifest in very distinct and disparate ways. “The project is about a shared history of movement and memory,” Das says. The exhibition asks “What can we speak about in this contemporary moment that is beyond [simply explaining] the transatlantic slave trade?”

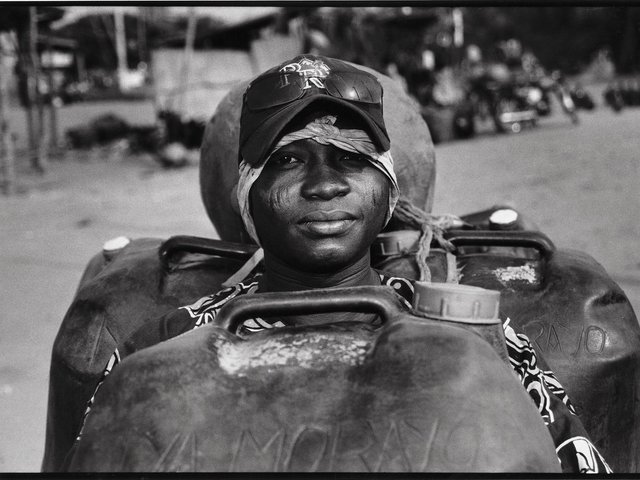

Bunmi Agusto’s Portuguese Soldier (2025) Courtesy of the artist & TAFETA

Return journey

The London-based Nigerian artist Bunmi Agusto’s latest body of work delves into her great-great grandfather’s story, a Nigerian man who was sold into slavery but later returned to his home country, leaving his loved ones. “I’ve often wondered why he left behind his wife and children,” Agusto says. “Through my research, I’ve learned that returnees were taxed to ‘immigrate’ to Lagos.” Centuries later, the two branches of the family got back in touch, and her grandfather and his Brazilian cousin often spoke by letter. While Agusto is unable to find these letters herself, this reconnection is the underlying narrative within her new works. “That ambiguity of lost history is also embedded in there.”

In her painting Collapsed Timelines (Popo Aguda) (2025), Agusto depicts a traditional wooden door in Yoruba culture, one of the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria. Historically, these doors were carved in high relief, revealing images of humans and animal figures. While these items were often not intentionally offering a narrative, they regularly gave insight into the period they were created, or before. One, said to have been crafted around 1910-14, currently at Denver Art Museum in Colorado, depicts women carrying pots, others with babies, fish eagles, soldiers, men with ceremonial swords and flywhisks, pythons and more. According to the museum’s description, these images are said to depict the Yoruba civil wars that took place during the 18th and 19th centuries.

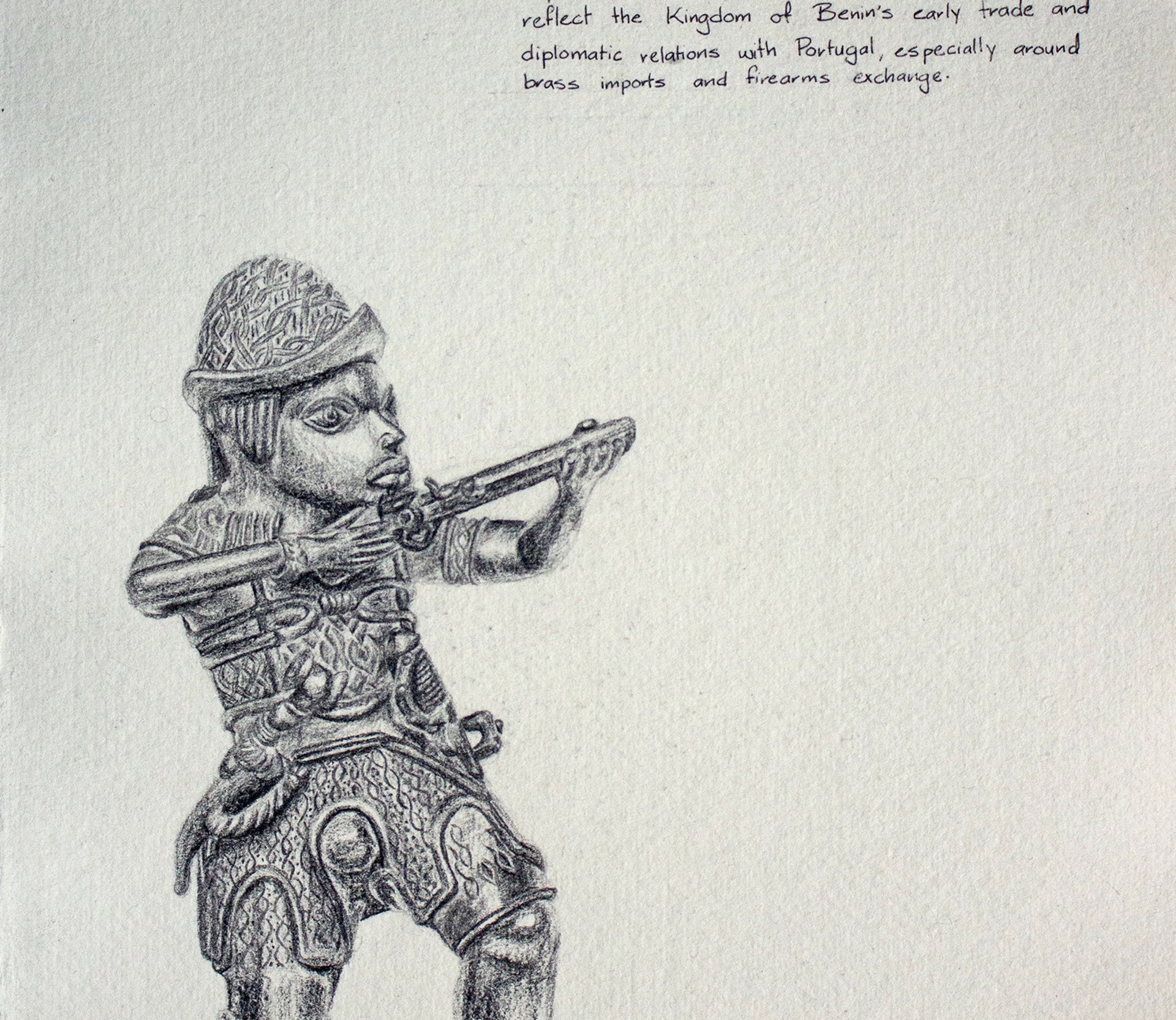

Agusto’s version portrays a host of iconography related to her research into her family’s connection to Brazil, from Portuguese soldiers (who forced African slaves into labour-intensive sugarcane plantations), to the Benin Bronzes, to currency from the times of the transatlantic slave trade. “The cowrie [shell] and the manilla [metal bracelets] were the two primary currencies used during that era, with the cowrie functioning as the small denomination of currency and the manilla a larger one,” Agusto says. “What was interesting was that, when slaves were bought from Benin, they would accept the manillas, and since they were made of bronze, they were melted down to make the Bronzes.”

Augusto also imagines a scenario where the door tells you the story itself. In each piece in this series, a section of the wood is replaced with a green window. In Collapsed Timelines, this space presents “a façade of one of the Brazilian buildings in Lagos that was demolished in 2015, which is why [I’ve depicted it] in stencil form,” she says, revealing that many people in the city were unhappy with it being taken down. “It speaks to a larger thing of Nigeria’s relationship with history, and oftentimes avoiding or unintentionally masking it.” She also depicts her grandfather sitting cross-legged in front of the disappearing building. Beside him stands a statue that is still in the city today. “It is the statue of Madam Tinubu, a prominent slave trader,” Agusto clarifies, noting its location at the centre of a roundabout leading into the Brazilian quarters of Lagos. “It is really odd that there’s this statue of a slave trader there.”

Diambe created Infinito Inquieto Imortal (2025) using egg tempera, a traditional technique Courtesysimoesdeassis.com/ERIKA MAYUMI

For the non-binary Brazilian artist Diambe, represented by Simões de Assis gallery in São Paulo, their work grapples with carrying multiple cultural identities and the complex history that that brings. “A lot of my work comes from navigating between where I come from and where I am now, between different histories that sometimes don’t align easily,” they say. “I was raised with stories that were always half in the past and half in the present; they were warnings but also ways of remembering.”

Material connection

Material serves as an important part of Diambe’s practice. Their painting Infinito Inquieto Imortal (2025), made using egg tempera, offers a natural landscape in pinks, purples, yellows and blues. “My generation of Afro-Brazilian artists are interested in reformulating traditions; for me, it’s using techniques that are related to [past] traditions,” they say, pointing out that egg tempera came to the country from Egypt. Diambe’s sculpture Mañana estaré lejos (2025) presents an abstract, green tree-like structure with two distinct yellow stars. “I was thinking a lot about stars when I made this set of works and how they guide movements through land,” they explain. But, most importantly, the piece is made out of bronze. Despite being denied a visa to Nigeria, they say they “had the opportunity to visit West Africa, the Republic of Benin, looking at how bronze sculptures were made” in the Benin Kingdom, now known as Benin City in Edo State, Nigeria. During this trip, they learned about the “very complex history” around the Benin Bronzes.

Mañana estaré lejos (2025) by Diambe Courtesy simoesdeassis.com/ERIKA MAYUMI

The relationship between Africa and Brazil is not a simple or easy one, but through their practices, each artist in Echoes in the Present has found a way to readdress narratives and traditions that are not always clear. Das notes that memory is a central theme of the show. “When you have this dislocation from a past, a history, an origin story, where much [of what is told] is carried through oral tradition, at some point gaps appear in that retelling,” she says. Many of the works acknowledge those holes and create narratives that underscore their presence.