The British Museum held a dramatic press conference today, announcing its campaign to save a gleaming gold, heart-shaped pendant—which offers an unprecedented window on to the relationship between Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon—for the nation. The historian Mary Beard and the actor Damian Lewis, the latter speaking via video message, both gave impassioned speeches as they spoke about the importance of raising £3.5m to purchase the object and ensure it does not disappear into a private collection.

The Tudor Heart, as it has become known, was discovered by the amateur metal detectorist Charlie Clarke in 2019, in a field in Warwickshire—and reported under the Treasure Act 1996, which gives museums “first dibs” on potential treasures. One side of the pendant is decorated with an image of a Tudor rose intertwined with a pomegranate tree, symbols relating to Henry and Katherine respectively; the other features the letters “H” and “K”, bound together with white thread. At the bottom of each face is the word tousiors, or “always” in old French.

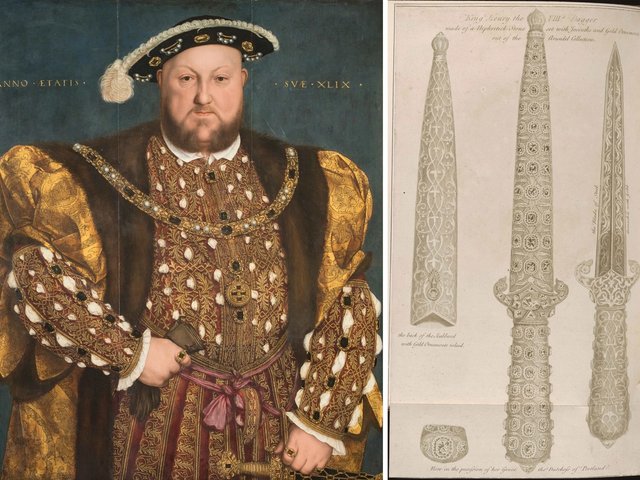

Rachel King, the curator of Renaissance Europe and the Waddesdon Bequest at the museum, tells The Art Newspaper that the object is entirely unique in the window it offers onto this period of British history. “We have absolutely nothing of this complexity or type surviving from Henry VIII's early reign,” she says. Until now, she adds, understanding of the “bling” from this era has been reserved to inventories and observations of paintings by artists such as Hans Holbein the Younger, but here you have a “tangible example”.

Research undertaken by the British Museum involving the study of invoices and other paperwork suggests the pendant may have been created for a tournament marking the marriage of Henry and Katherine’s daughter, Mary, to the French heir apparent, in 1518. It is possible, King says, that it was worn by a member of the entourage that day, or given as a prize; the weight of the object is such that it could only be worn by someone of high status, perhaps a “son of a knight or a baron or above”.

The pendant also comes with a golden chain and intricately carved clasp in the shape of a fist

© The Trustees of the British Museum

It is the opportunity to reframe conversations around Mary and Katherine that is among the most exciting aspects of the potential purchase, King explains.

“We have very little in Britain's museums that relate to those two figures and that's because of vilification through anti-Catholic bias over the past 400 to 500 years,” she says. “What we want to be able to draw out is Katherine as her own person, a queen in her own right, somebody who was of significantly higher status than Henry [going into the marriage].”

Mysteries still surround the work: how it ended up in Warwickshire, for example, and how it came to be buried, which the museum hopes will be solved through further investigation. The valuation of £3.5m was decided by the Treasure Value Committee, an advisory body sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, and comprising curators and other experts.

The campaign, which runs until April 2026, has already received one donation of £500,000—from the Julia Rausing Trust, one of the two main donors behind the National Gallery’s forthcoming £375m extension.

The efforts come at a time when the British Museum is working to raise funds for its much-discussed masterplan, which will involve the revamp of existing galleries and the creation of new spaces such as an Energy Centre, designed to phase out the use of fossil fuels. The run-up has seen the establishment of several fundraising initiatives, including the British Museum Ball, an event moulded around the Met Gala in New York—at which prominent figures from the worlds of art and fashion are expected to grace the red carpet.

If such ambitions pose a challenge in regards to prioritising, that is something King is happy to be separated from. “Thankfully it’s not my task as a curator,” she says. “The valuation at present is a good one. Should we not reach it, the object will be returned to the finder, and if there’s then a bidding war, this would certainly go higher than the museum could achieve.”

Mary Beard, meanwhile, praises the “bodily connection” the object forges between us and the wearer. The museum, she adds, is best placed to ensure that it is “shared by all of us”, and that we go on “debating it, discussing it, studying it, puzzling over it”.

The Tudor Heart is on display in Gallery 2 at the British Museum until April 2026.