The American painter Wayne Thiebaud’s (1920-2021) mouthwatering depictions of glossily iced cakes, slices of cherry pie and deli counters arranged just so, present a thoroughly American reimagining of the traditional genre of still-life. The works came to public attention in the early 1960s, just as Pop art hit the US with what the critic Harold Rosenberg described as “the force of an earthquake”.

The 21 paintings that form the focus of the artist’s first museum exhibition in the UK, at the Courtauld Gallery, are almost all on loan from public and private collections in the US, including the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation, established by the artist’s family. The Californian artist is celebrated in his home country, but is little known in Europe; the Fondation Beyeler’s 2023 Thiebaud survey was the German-speaking world’s first encounter with the artist. Recently, the Courtauld became the only UK institution to have a Thiebaud drawing in its collection, and Cake Slices (1963) features in an accompanying exhibition, Delights, of works on paper by the artist.

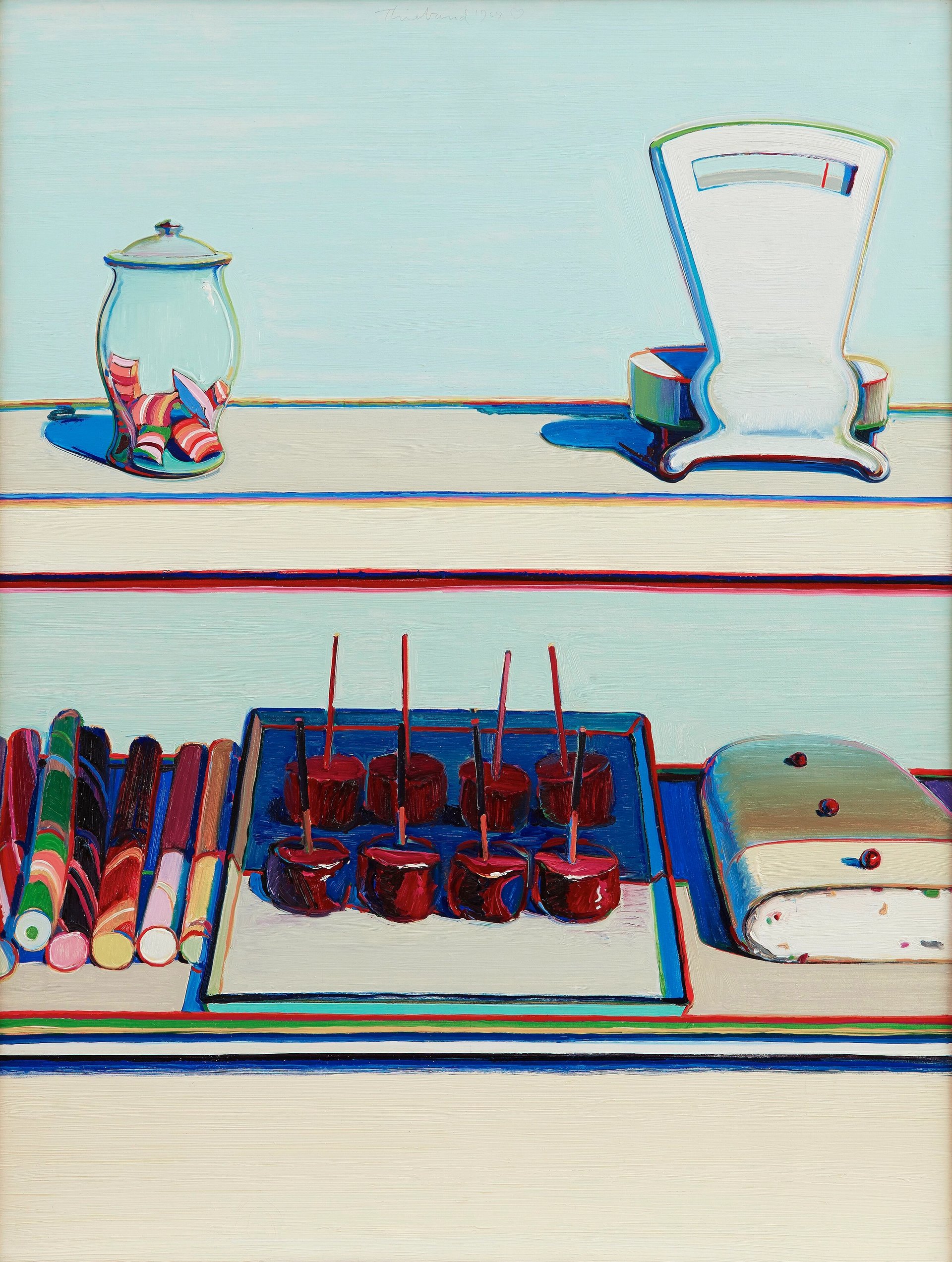

Seeing his work first hand is a revelation, says Barnaby Wright, the co-curator of Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life. “The first thing you realise is just how extraordinarily painterly it is,” Wright says. “Reproduced, it’s flat and slick, but in the flesh it’s not like that at all. Although he’s associated with the Pop art of the 1960s, his real lineage, and where he saw himself and his art coming from, is the earlier tradition of still-life painting.”

In 1961 Thiebaud shared his first exhibition with a fellow unknown artist, Andy Warhol. But for Wright, it is Thiebaud’s relationship to artistic heroes such as Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, and their 18th-century antecedent Jean Siméon Chardin, that is most germane.

“Extraordinarily painterly”: reproductions of Thiebaud’s works, like Candy Counter (1969), can lack the depth and richness of the originals, the exhibition’s curator says © Wayne Thiebaud/VAGA at ARS, New York and DACS, London 2025

Thiebaud was profoundly influenced by Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), one of the Courtauld’s most famous paintings. “We’re really pleased that you could be looking at Manet’s Bar in one room, and then in another room be looking at one of Thiebaud’s candy, or deli counters,” Wright says.

“He definitely sees himself as a painter of modern life in the way that Manet was, or to some degree Cézanne. He felt that these objects—slices of pie, or gumball machines or pinball machines—had something meaningful to say about the era he was living in,” Wright says, “and that that era, and those objects, would disappear before long, just as surely as those that Manet or Chardin painted had disappeared.”

Paintings with ‘empty hearts’

This undercurrent of melancholy echoes the memento mori intrinsic to the tradition of still-life painting, conveyed in areas of deep, slightly jarring shadow, or the softening ice cream in Three Cones (1964). “His paintings often have these empty hearts to them”, Wright says. “The counter will appear bare at points, or where you expect to see a figure there is none; or, there’s a single, rather lonely slice of pie.”

Despite their shared language of “commonplace objects”, Thiebaud’s sincere commitment to his subject, and to painting itself, contrasts with Pop art’s ironising celebrations of mass production and machine-made advertising images.

The artist honed his approach after meeting one of his heroes, Willem de Kooning, in 1956, who urged him to paint what he knew and cared about. For Thiebaud, this meant drawing on his years as a commercial artist developing in-store product displays for a drug company. He had started out as an “in-betweener” illustrator for Walt Disney while still at school, and the strategies he learned throughout his career were put to use in his paintings, in which he combined “cheap tricks”, such as repetition without uniformity to create “tempo” with lessons gleaned from fine art. He was fond of rehearsing Cézanne’s instruction to “treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone”, describing his slices of pie on a saucer as exercises in geometry; his use of complementary colours to outline objects was informed by Josef Albers.

Thiebaud was an untrained artist, who became an inspirational and dedicated teacher, a career path that he chose deliberately as a means to paint full time, beginning in 1953 with his first post at Sacramento City College. For him, the clarity of thought required to teach was its own education.

America’s vision of post-war abundance had already darkened by 1962, the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Thiebaud’s optimistic but wistful paintings chart the beginning of a decade of anxiety that challenged and changed American identity in a way that resonates anew today.

• Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life, Courtauld Gallery, until 18 January 2026