Many eyes in the international art world are on Nigeria this autumn, thanks in part to Tate Modern’s blockbuster Nigerian Modernism exhibition (until 10 May 2026), and an explosion of activity in the country itself, including the opening of the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) in Benin City. The excitement of this moment is being felt at London’s 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, held in Somerset House (until 19 October). “It really means a lot to have MOWAA arriving,” says Sosa Omorogbe of the nomadic gallery, The 1897. The gallery is presenting works including a series of watercolour paintings by the London-based Roisin Jones. “I never thought I’d see the day that my friends would be messaging me saying, ‘I’m coming to Benin for the weekend.’ It’s overwhelming.”

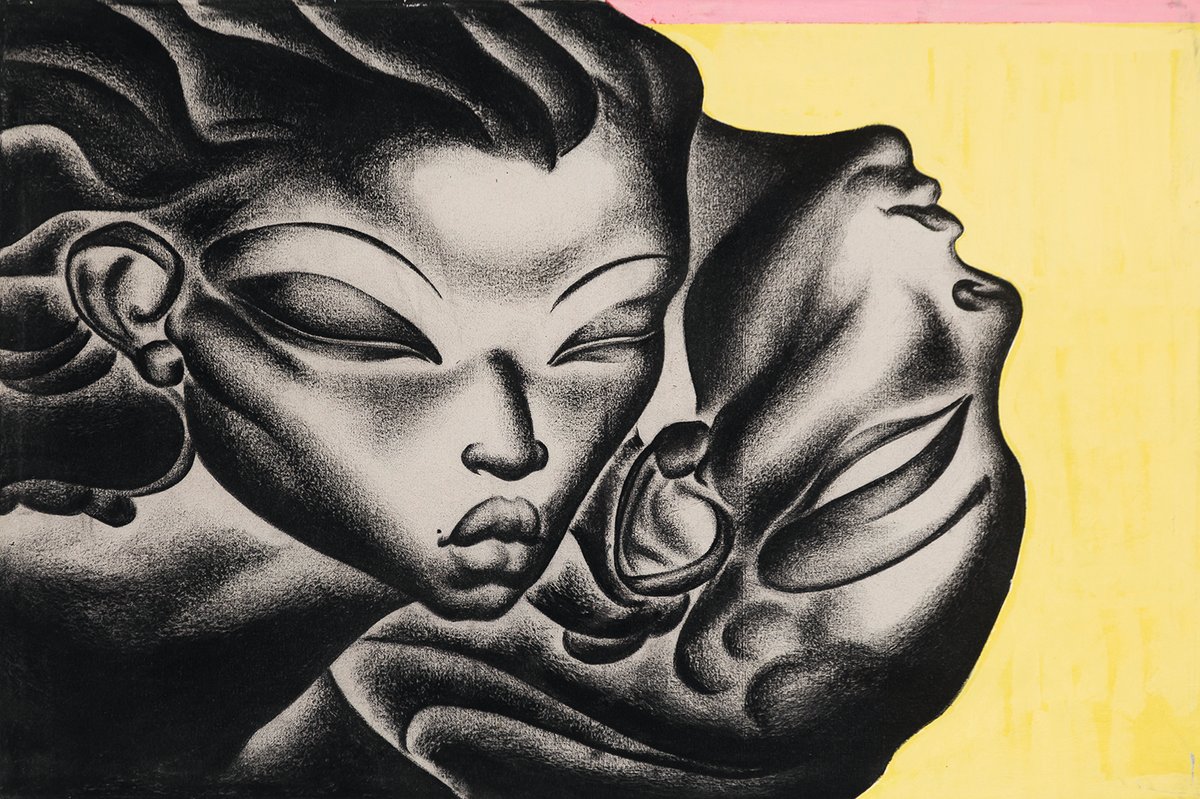

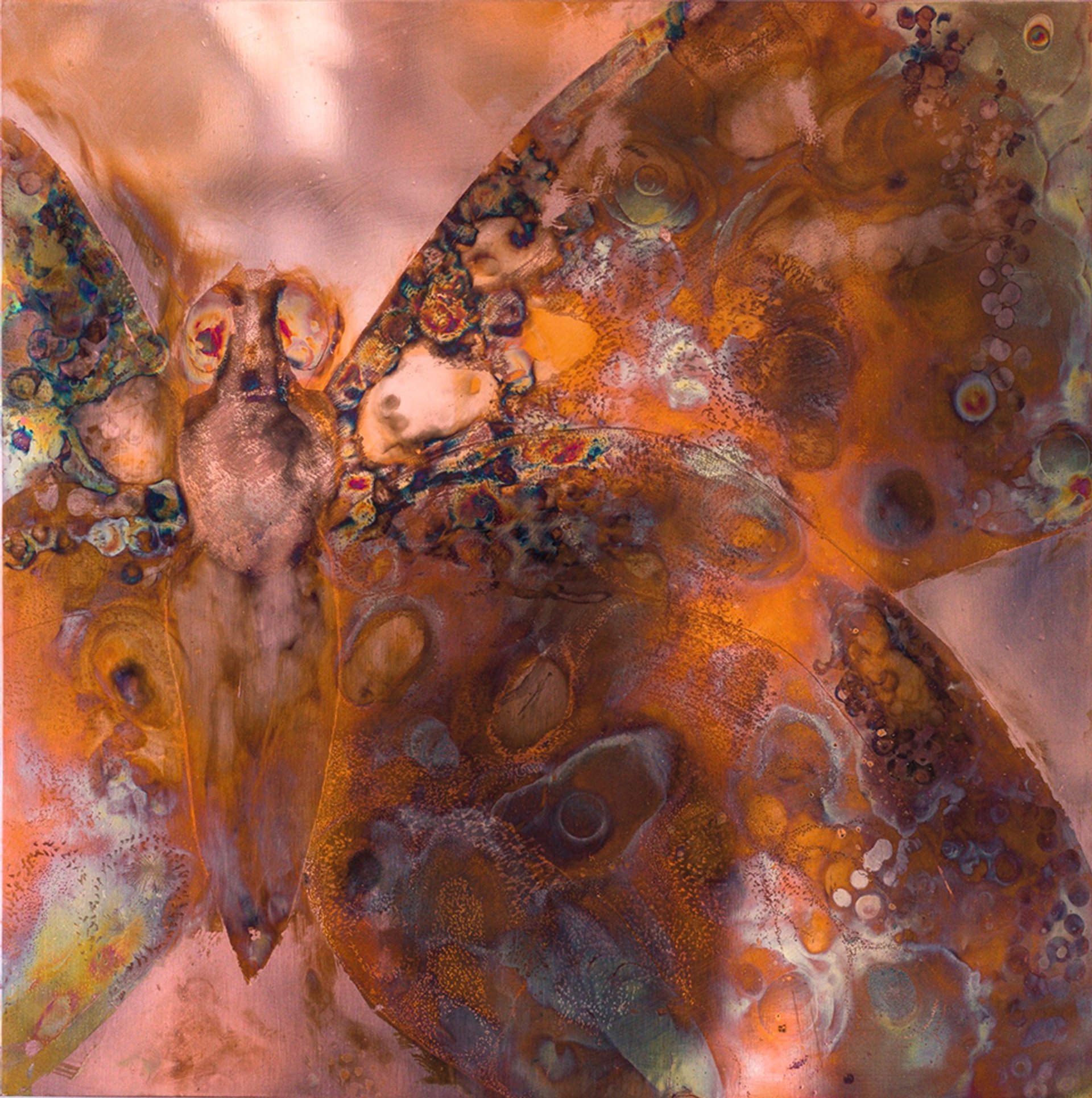

Exhale (2024–25) by the London-based artist Roisin Jones

Courtesy the Artist and 1897 Gallery

For Obida Obioha of O’DA gallery in Lagos, it is an opportunity to shine a light on the richness of Nigeria’s contemporary art scene. “Nigerian Modernism is wonderful because it can show where it came from, but we can show where it’s at today, which is extremely contemporary and on the ball,” he says. The gallery is offering sculptural paintings by the Lagos-based painter Afeez Onakoya, as well as works on wood by the Londoner Paul Majek and acrylic pieces by Simon Richard Ojeaga from Edo State in Nigeria.

A broader perspective

Just as notable at the fair, however, are galleries championing the work of artists from outside of West Africa—whose gallery ecosystems are more nascent. Danda Jaroljmek, the director of Circle Art Gallery in Nairobi, focuses on introducing under-represented artists from East Africa to the international market. “It’s really important because I think people generally know far less about art from this region,” she says. Circle’s booth includes a group of large-scale, impressionistic monoprints by the Ethiopian artist Tiemar Tegene, priced at $7,000 each—two of which had been reserved at the time of writing.

Sana Ginwalla of Everyday Lusaka Gallery debuted at 1-54 this year. “I wanted to present Zambia on a more global stage,” she says. “Because a lot of times West Africa and South Africa are very present at international fairs, which I think is great, but I also think it needs to open up to other countries which also have so much talent”. She is showing mid-century work by Alick Phiri, whose posed, personal photographs (offered at £300-£900 each) were made at a time when the use of cameras in Zambia was a “privilege”. They form part of an installation celebrating the country’s first photography studio for Black clients, Lusaka’s Fine Art Studios, founded in the 1950s—and have already drawn institutional interest.

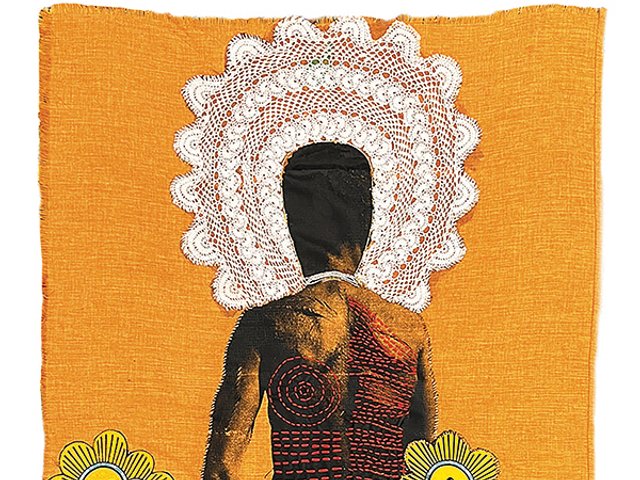

What is apparent among many of the gallerists is a sense of solidarity and shared optimism. “You cannot do things alone,” says Olugbemiro Arinoso, the founder and director of the Lagos-based Affinity Art Gallery, which sold at least two works, including a large fabric wall work by Samuel Nnorom for £22,500. “You can see in our booth, we don’t just work with Nigerian artists—and it’s very important for us to be able to pick from each other, and to learn from each other.”