The Chicagoan artist Tony Fitzpatrick died of a heart attack on 11 October. He was 66. A prolific and expansive artist, Fitzpatrick was a big guy who epitomised Chicago with his strong work ethic and a personality that was as brash as it was sweet.

He was an artist, poet, author, actor and first-rate raconteur, which made him a popular guest or co-host for panels, radio programmes and podcasts. He was perhaps best known for his collages, etchings and works on paper, which incorporate text plus disparate imagery and materials including birds, dogs, boxers, baseball, tattoo art, colour wheels, targets, old matchbook covers, Chicago and the number nine (which was also tattooed on his arm in red). His work is widely collected and represented in museum collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Fitzpatrick was born in 1958 and grew up in a large Irish Catholic family in the western suburbs of Chicago. He worked as a taxi-driver, bouncer, waiter, janitor and boxer before committing himself to art. He ran a storefront gallery called The Edge in Villa Park for five years, which relocated in 1989 to the then-ungentrified south loop of Chicago. Renamed World Tattoo, the gallery’s opening night parties were legendary. Before it closed in 1994, World Tattoo hosted an exhibition of the Los Angeles artist Jim Shaw’s Thrift Store Paintings on behalf of the newly established Society for Outsider, Intuitive and Visionary Art (now known as the Intuit Art Museum).

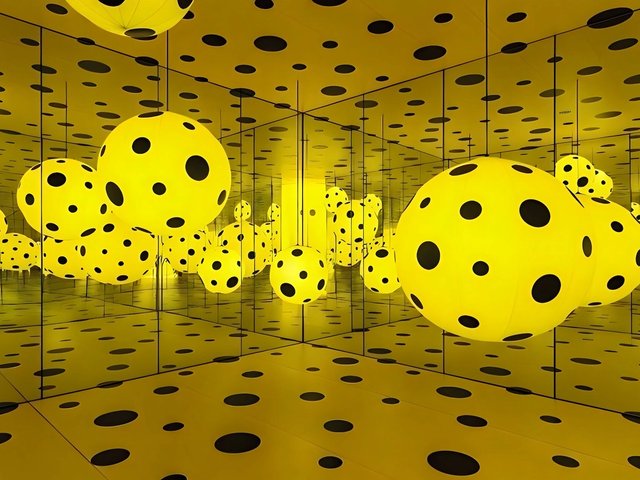

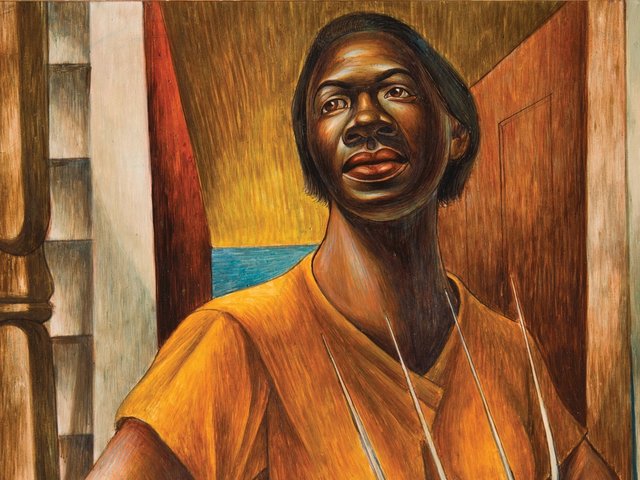

Installation view of Tony Fitzpatrick's solo exhibition at the College of DuPage's Cleve Carney Museum of Art, Jesus of Western Avenue Photo by College of DuPage Newsroom, via Flickr

Fitzpatrick knew how to get press and befriend the right people, but his skill and the quality of his work matched his bravado. He was generous to young artists and a vocal defender of labour unions and all underdogs.

As the news of his death spread on social media and in local news reports, so did the stories and tributes. Among the institutions honouring the late artist was Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater, where Fitzpatrick performed repeatedly over the years. He was to present a live show based on his new book, The Sun at the End of the Road: Dispatches From an American Life(Eckhartz Press), that was set to run into early November. On the exterior of Steppenwolf is Fitzpatrick’s largest work and only outdoor mural, Night and Day in the Garden of All Other Ecstasies, which was installed in 2021.

“Tony was an extraordinary Chicago artist—and we were honoured that he considered Steppenwolf to be one of his artistic homes. As a performer, Tony was featured in five productions at our theatre across the span of more than two decades,” a post on the theatre’s Instagram account reads in part. “His spirit will live on through his work. We are honoured to have counted him as an artistic collaborator and friend.”

Installation view of Tony Fitzpatrick's solo exhibition at the College of DuPage's Cleve Carney Museum of Art, Jesus of Western Avenue Photo by College of DuPage Newsroom, via Flickr

Fitzpatrick had been diagnosed with interstitial lung disease this summer. He posted a photo of himself on Instagram wearing the nasal oxygen tubing that he would be required to wear all the time. Of his new reality he wrote that he was “one lucky Bastard” with “an amazing family and friends”.

Fitzpatrick was hospitalised for four weeks and was awaiting a double lung transplant when he died. During that time, he never stopped creating. Besides the Steppenwolf production, he was working toward a new exhibition at a tattoo parlour and promotional events for his new book. With the current US president slamming his beloved Chicago as a “hellhole”, he very much intended his book to “be part of the counter-narrative to Trump’s lies”, he recently told Block Club Chicago.

In the book’s introduction, Fitzpatrick wrote: “What follows here is some of what I remember, some of what I have learned and damn near all of what I love—birds, stories, people and dogs. It is all part of a less-than-holy life. Are there any great parables to be gleaned from these dispatches, poems and pictures? I haven’t a clue. What’s most important is all that I learned along the way: that which is for remembering, for not forgetting.”

Fitzpatrick is survived by his wife, Michele, and their children, Max and Gabrielle Fitzpatrick.