In March, the Charity Commission signed off on the Sir Percival David Foundation’s decision to gift its namesake’s extraordinary collection of Chinese treasures—including a pair of blue-and-white David vases from 1351 and a 1,000-year-old Ru ware bowl stand—to the British Museum. The donation, valued at just shy of £1bn, broke all records. It has pushed the museum’s Chinese ceramics holdings to 10,000 pieces. The commission ruled that it furthers David’s intention that his collection “inform and inspire people”.

The British Museum Act 1963 clearly outlines a very narrow set of conditions under which the museum is permitted, by law, to deaccession an item (if it is a duplicate or printed matter made after 1850 of which the museum holds a decent photo; if it is unfit to remain or too damaged to be of use). But quite what it does acquire—and how—is an altogether more fluid proposition. Since the museum’s founding in 1753, its acquisitions, in shape and method, have altered considerably.

Claude Lorrain’s View from Monte Mario (around 1640) was bequeathed by Richard Payne Knight in 1824 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Of the museum’s eight million items, conflict, colonial exploitation and missionary activity resulted in a significant proportion. Today, however, things come into its possession via donations, bequests, purchases and commissions, as well as excavations and the portable antiquities scheme. Two notions—the everyday and the ephemeral—underpin what curators look for. “We want objects that speak and tell a story about how people lived,” says Tom Hockenhull, chair of the Acquisitions Committee and keeper of the Money and Medals department since 2022. “It’s about showing how things are reused and recycled and what people felt about their position in society.”

Any object under consideration has to pass several practical and ethical tests. First is how it can be safeguarded. As Hockenhull puts it, “Once an object has arrived, we can’t deaccession it, which means we have these items until the sun explodes.” So the team thinks about what it is made of and under what conditions it will need to be kept—and the attendant cost for doing so. Second are the cultural or bequest-led stipulations placed on its display. If an object is connected to a specific community, is said community even happy for it to go into a museum? If it is connected to a specific landscape, can the museum accommodate it being displayed outdoors? “We need to think about all these things, as part of relationship building,” Hockenhull says. “We exist to serve the public, and that public has changed over time.”

We exist to serve the public and that public has changed over timeTom Hockenhull, acquisitions committee chair, British Museum

Today, that public is global. On the opposite end of the donation spectrum to this year’s £1bn high are the daily offers from private individuals. There is one member of staff at the British Museum among whose tasks it is to man an inbox specifically to field these proposals. Every day, people will write in saying, “I have this thing. Might you be interested?” “And every day,” says a museum spokesperson, “we’ll write back, saying, ‘No, thank you. We don’t acquire from individuals.’”

Serendipitous donations

That is, until they do. “Sometimes, you’ll have a bit of back and forth and eventually you’ll say, ‘Actually, this is quite interesting,’” Hockenhull says. An object might pop up that relates to a curatorial research stream, or that fills a gap or nicely complements something already in the museum.

Edwardian coin defaced by a suffragette © The Trustees of the British Museum

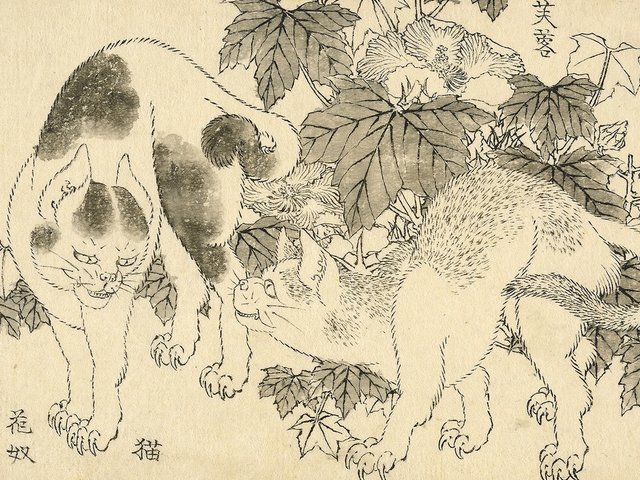

Other times, it is just a nicer example of something the museum already has. As a prolific lender of objects, it is the institution’s interest to have more than one of all kinds of popular things other institutions tend to borrow—from prints (which can only be shown one year in 10) to Roman imperial busts and Edwardian coins defaced with the suffragette slogan “Votes for Women”, of the kind the Private Eye editor Ian Hislop picked out for the I object exhibition he curated in 2018. The annual report for the year ending 31 March 2025 highlighted the recent acquisition, with support from the JTI Fund for Japanese Acquisitions, of a set of Samurai armour. The museum, of course, has previously celebrated similar purchases, most notably in 2017. But the opportunity to buy a complete set was not one the Department of Asia could turn down. As Hockenhull highlights, the value of such a set is that they were often assembled over generations, thereby showcasing distinct eras of craftsmanship. “So we jumped on that,” he says, because a Samurai exhibition is soon to be announced.

Another highlight of the 2024 acquisitions list illustrates the museum’s ability to exercise the nation’s right to retain works of cultural significance. In July 2024, following an export ban sanctioned by the government, the British Museum purchased a rare 17th-century drawing by Samuel Cooper, Portrait of a Dead Child, for £114,300 (plus VAT of £4,860), with funds from the Ottley Group and its own General Acquisitions Fund.

The museum counts eight departments and lists, along with each keeper (or head of department), close to 90 other assistant keepers, heads of section, curators and research fellows. In other words, a lot of extremely knowledgable people who would know what to spend money on. But not all will get to do so.

Acquiring via fieldwork

“A curator of Greek pottery is, in all likelihood, not going to make many acquisitions during their career, because, for one, we’ve got one of the best collections of Greek pottery in the world—we don’t need more,” Hockenhull says. By contrast, those departments with a contemporary focus—the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, say—face countless exciting opportunities to work with living artists and to acquire via fieldwork. Curators look for ways to record and preserve local heritage and crafts practices, as part of research.

“Overwhelmingly, the greatest strength, by volume, of our collections is that of the last 200 to 300 years, particularly focused on the last century,” Hockenhull says. This runs the gamut from the glorious to the mundane: from the anonymous donation, in 2024, of the Paris-based Taiwanese artist Anna Hu’s Enchanted White Lily Bangle I (a floral bracelet of gold, brass and silver with a 30.48 carat rubellite gemstone for a pistil) to the 20th-century communist currencies (bonds, coins, banknotes, posters and medals) Hockenhull purchased in 2017 to fill a gap in his department’s holdings.

More than any specific type of object, the founding principle of the museum—as laid out by Hans Sloane, whose personal collection was the primary of the three it started out with—was that its collection expand, that it be a living thing. “We very much operate under the ethos that a static collection is a dead collection,” Hockenhull says. “We’re trying to show the things that humans have made and used since the dawn of civilisation to the present, which means we need to keep collecting.”