Jeanne Lanvin was a trailblazer in 20th-century French fashion and interiors. The first she worked on herself, moving from children’s clothes to couture, to become celebrated both at home and abroad from 1910, when she joined the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture, until her death in 1946. The second she worked on with sought-after stars of the day: Armand-Albert Rateau and Eugène Printz. Rateau designed the interior of Jeanne’s magnificent home at 16 rue Barbet-de-Jouy in the 7th arrondissement of Paris; Printz did the interior of her office at 22 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, where clients could view themselves from every angle in the three-way mirror that slid on a curving track. Completed in 1930, this is where Peter Copping and Olivier Gabet have their own conversation 95 years later, in a room where nothing has changed.

A dress from Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2025 collection, the first under Peter Copping’s artistic directorship Filippo Fior/Gorunway.com

The house of Lanvin has never closed since Jeanne opened her first millinery store in 1889, aged 22, though it has gone through many changes. It was sold by the family in 1980 to L’Oréal and is now part of the Lanvin Group. Since July 2024, British-born Copping has been its artistic director, a designer with experience at Louis Vuitton, Oscar de la Renta and Balenciaga, where until recently he ran the couture department. A man with a wealth of design knowledge, he has nonetheless found the Lanvin archive—a deep trove of carefully conserved clothing, embroidery, dolls, textiles and accessories—to be unlike any other he has worked with.

Olivier Gabet of the Musée du Louvre © 2022 Musée du Louvre/Audrey Viger

Lanvin’s artistic director Peter Copping © Riccardo Olerhead

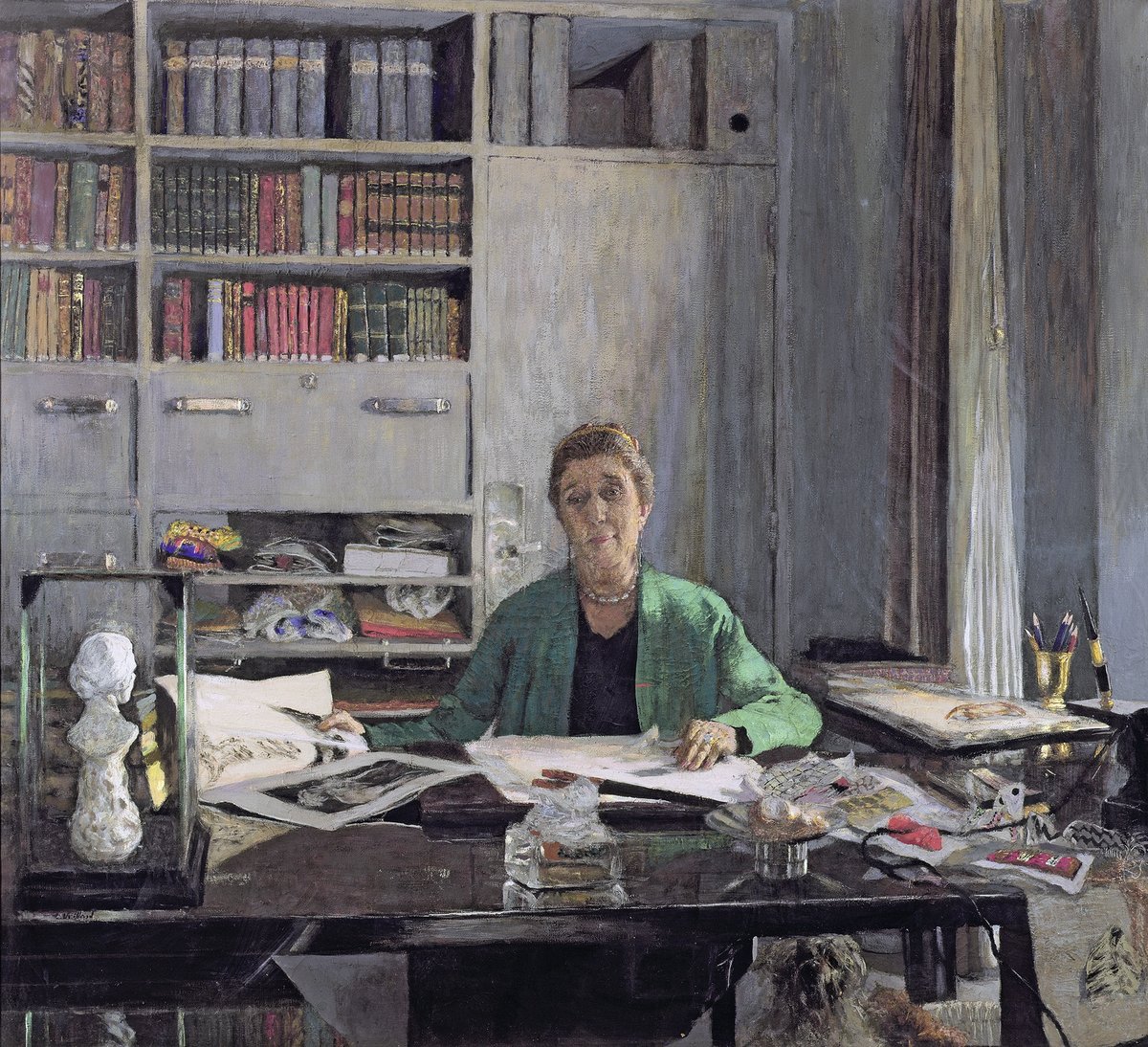

Gabet is the director of the Department of Objets d’Art at the Musée du Louvre—a sprawling 9,000 sq. m space that encompasses everything from medieval religious icons to 19th-century glass, and where this year he curated an exhibition, Louvre Couture, of 99 looks borrowed directly from 45 fashion houses. For nine years, Gabet was the director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, also part of the Louvre. There he was the custodian of complete rooms taken directly from Jeanne Lanvin’s apartment—including the bedroom, boudoir and bathroom—which are now on permanent display.

CR You both have a special connection to Jeanne Lanvin. How do you see her as a woman and an exceptional creative force, and how much has her archive assured her legacy?

OG I was desperate to put on a Lanvin exhibition when I was at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs from 2013 to 2022. She seemed such an important figure—as a woman, a collector, a fashion designer, a space maker. Sadly, it never happened, but I’m always ready to talk about Jeanne.

PC That would have been an amazing show. When I arrived at Lanvin, one of the first things I did was to revisit the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. It felt really important to look at those interiors again, as a way to figure out who this woman was. Being in the bedroom, with its blue silk-lined walls embroidered with palm leaves and daisies, was to be immersed in her universe. Even the gilded door handles are fitted with paperweight balls—apparently, she collected them. And then there’s the bathroom—stucco walls, a floor tiled in black, beige and white Hauteville marble. At times the tiles are arranged to look like Modernist carpets. They have appeared as prints in my first collection. And of course, there’s the padded leopard-print toilet seat. The decadence!

A leopardskin coat from Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2025 collection. Jeanne was a fan of the pattern–she had a leopardskin print toilet seat in her bathroom. “The decadance!” as Peter Copping says Filippo Fior/Gorunway.com

CR What kind of woman do you think she was?

PC She came from a very humble background, so her style and taste came from within; she had an innate sense of elegance. Then, as a businesswoman, she ran a wide-ranging operation, much more than a couture house. By the 1920s, she had branched out into furs, menswear, lingerie and perfume. She acquired her own dye factory in Nanterre, so she was able to achieve colours on certain fabrics that other people at the time would have found difficult or impossible. She ran her own embroidery ateliers as well. Her daughter was also an active participant in the Lanvin enterprise, as a muse, but not a passive one.

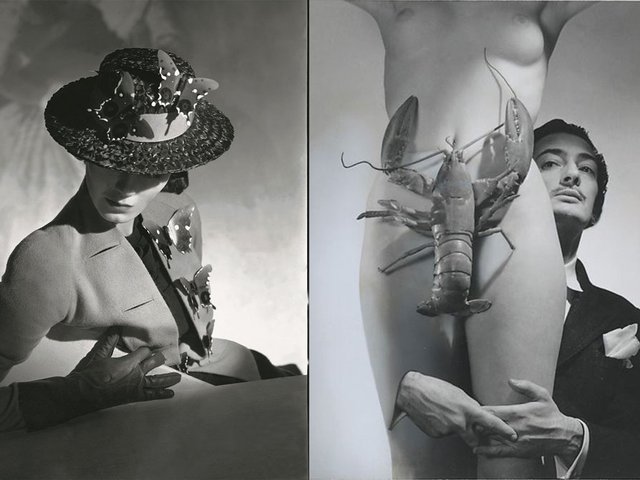

OG I’ve just read the biography of her daughter, Marguerite, by David Gaillardon, and I saw Jeanne in a different light—maybe not so easy. I mean, she was definitely generous, and she enabled Marguerite to become an excellent musician and marry into the aristocracy; she became Countess Marie-Blanche de Polignac. Jeanne, too, had married well, to the aristocratic Emilio di Pietro. But she comes across as a very reserved person who would prefer to sit in the corner. Her daughter, on the other hand, is surrounded by all these dashing people. She’s very social. She knew all the great musicians of the early 20th century: Satie, Poulenc, Fauré. We all know about Elsa Schiaparelli, the socialite, and Gabrielle Chanel, the social climber. Lanvin is the third in that triumvirate, the older one, the matriarch. She built her empire quickly, making strong aesthetic decisions about who she chose to collaborate with—the designer Armand-Albert Rateau, for example. She married, divorced, remarried and paid for everything for both her former husband and her new husband. She seems very ahead of her time.

PC If you were to compare her to someone today, it could be Miuccia Prada, another strong, creative businesswoman. Do you remember the time Mrs Prada arrived at the Met Gala in 2023, looking perfect—satin pants and a satin tunic, nothing to do with Met Gala-style fancy dress?

OG Oh, completely! She didn’t give a hoot about the red carpet. She knows it’s her duty to be there, but she walks in like it’s a normal day. Very Jeanne Lanvin.

Jeanne Lanvin’s office Dominique Maître/Penske Media via Getty Images

CR If Prada is today’s intellectual, then Lanvin, too, was concerned with her legacy and her archive. She seems to have wanted to catalogue all of her work in quite an academic way.

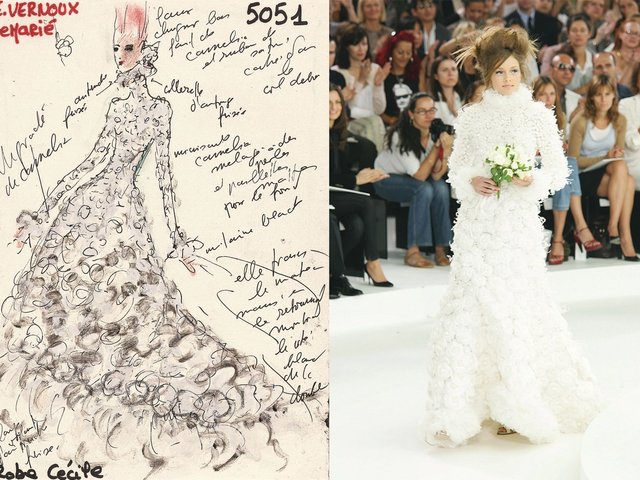

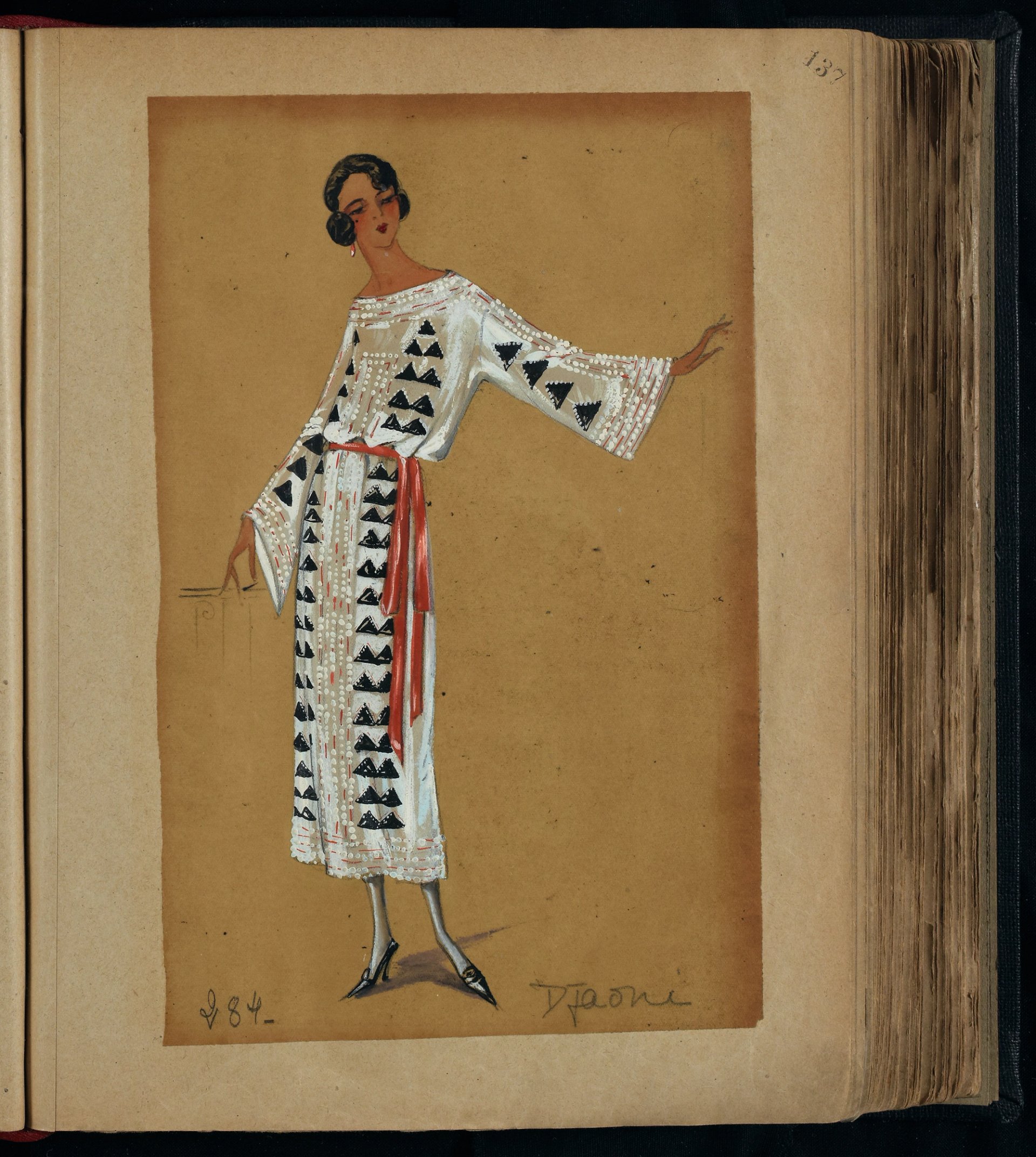

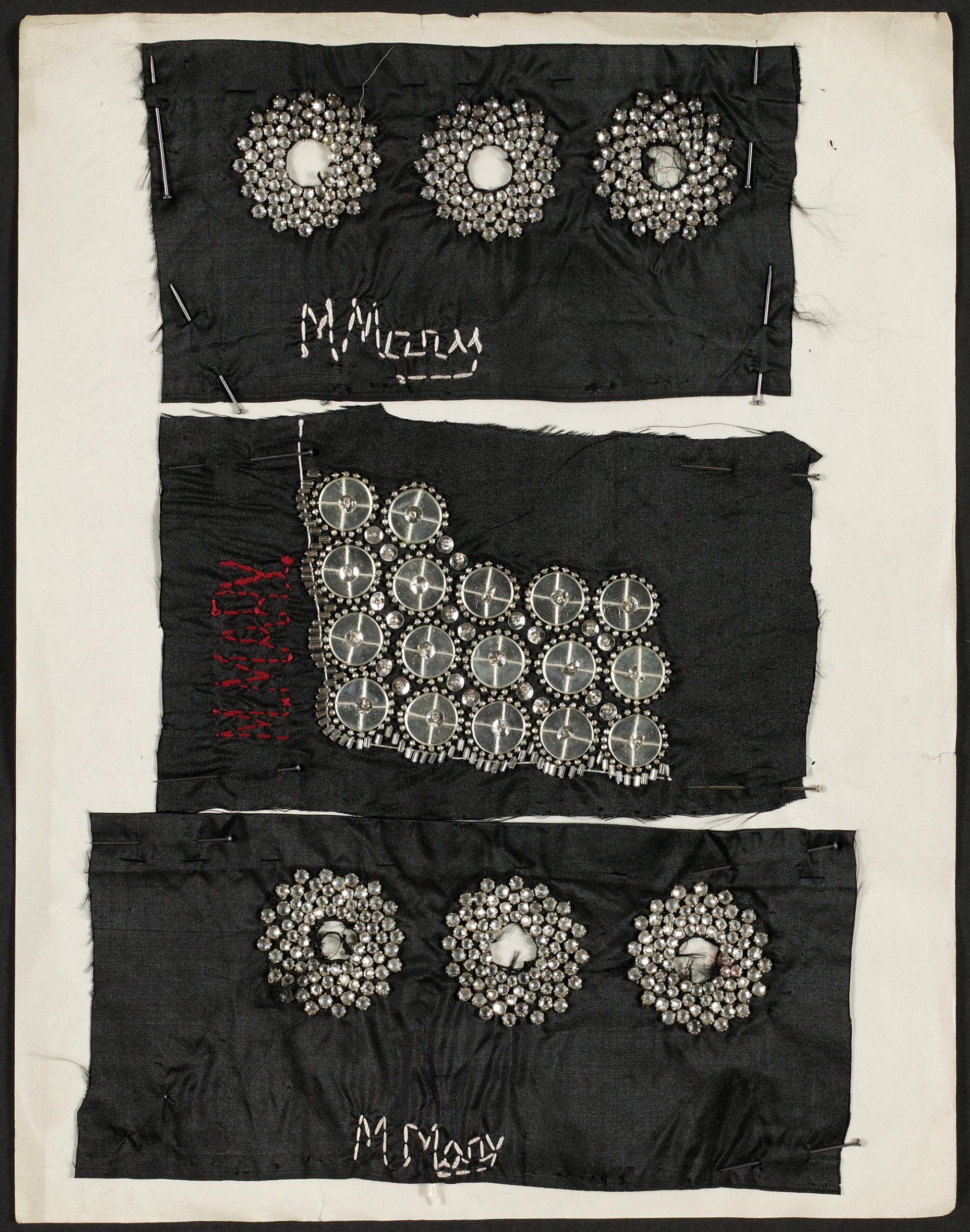

PC I’ve been told she wanted to set up a museum, and that would explain why the archive is so in-depth. It’s housed just outside of Paris and contains thousands of pieces. I like the embroidery samples most of all, swatches upon swatches. A lot of them tend to be geometric designs and they’re pinned on paper that has been recycled—old client orders. So you have information about a client’s acquisition, and often some personal comments like: “She’s gained a bit of weight.” It’s a gorgeous insight. Some of the designs I’ve used directly, like this one of large mirror sequins on a silver embroidered panel.

OG The archive provides a wealth of information for us as historians. The couturier’s job was to ensure that you’d never dress two clients exactly the same way—there’s a very personal relationship.

PC We have a lot of clothes from the 1920s that are very beautiful, very fragile, very inspiring. But the silhouette doesn’t necessarily do it for me, it’s flat. When you look towards the 1930s, it becomes more interesting—still close to the body, but more evolved. Though the necklines are modest and sleeves or capes cover the arms at least to the elbow, there’s a definite sex appeal in the way certain parts of the body were revealed. A dress might have an open back or an interesting side slit. It’s very subtle and seductive. It’s a long way from the curves and corsetry of the 1940s and 1950s.

a sequinned top from Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2025 collection Filippo Fior/Gorunway.com

A jacket in green velvet from Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2025 collection inspired by the Vuillard portrait of Lanvin Filippo Fior/Gorunway.com

OG My period would be the 1920s. She’s the only one working with that kind of silhouette, and she’s super-powerful. In 1925, she was invited to organise the fashion section of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, a landmark event in the history of taste and style, which eventually gave us the term Art Deco. She embodies that moment completely. I get excited by people who command some kind of transitional moment, and Lanvin is one of them. Chanel also came from a very simple background and had some revolutionary ideas around liberating women through dress. But when you see [Chanel’s] lifestyle, in the apartment on rue Cambon, it was all flowers, crystal, Boulle furniture. Lanvin, by contrast, brings something of the Old World to the New World. She loved 19th-century sulphur glass, which was the taste of chic people at the time, and looked back to the 19th-century Second Empire, which was coming back into fashion. She’s modern with a twist. Equally, Rateau’s approach is not radical. In the bas relief in Lanvin’s bathroom, you can see that Rateau had visited Herculaneum and Pompeii [in 1914], but it also refers to Renaissance tapestry with stags and birds.

Lanvin's bedroom, lined with lavishly embroidered silk © Les Arts Décoratifs.

Lanvin’s marble-and-bronze bathroom (1924-25), designed for her Paris apartment by Armand-Albert Rateau © Les Arts Décoratifs.

PC What I love in her work and the interiors is the level of quality, the love of craftsmanship, and that sense of transition that you speak about, Olivier. When I visited the Lanvin rooms at the Musée des Arts Décos, I discovered that some textiles had been replaced, but the original faded fabric removed from some of the chairs was in storage. We did a colour match of that faded blue fabric and I used it in the first collection in very subtle ways, in linings for example. It’s the Lanvin blue of today.

OG Quality pervades her world. She had a wonderful collection of Impressionist paintings, really good works by Renoir and Monet and Boudin. And of course, Édouard Vuillard, who was her contemporary. He was a witty, smart, intellectual guy, quite edgy for his time, and she chose him to paint her portrait. It’s iconic, and an expression of power.

An illustration, created by an in-house artist, for an outfit called Djaoni by Jeanne Lanvin from 1920. The chiffon fabric of the dress is embellished with fine strips of gilded leather and beading © Lanvin Heritage

PC That portrait inspired one of the pieces for autumn/winter 2025. I translated the green velvet jacket she is wearing into a menswear piece. We’ve tried to look at her in her entirety in the way we’ve built the collection. The black and gold dresses, for example, represent her elegance and power. Shoes designed for a black-and-red outfit called Polka inspired the footwear. I didn’t want to look at the archive in an academic way, it was more a case of what resonated with me.

OG In most houses, the archive has become the accepted framework for continuation. But it’s important how you use it. It shouldn’t limit the creativity of a contemporary designer. It’s great how you’ve treated it as a catalyst, Peter. And Lanvin offers so much—rooms in a museum, a silhouette, a jacket for the Comtesse Greffulhe based on the tiles in the [Paris] underground.

Embroidery from the treasure trove that is the Lanvin archive © Lanvin Heritage

PC It’s a gift. At Nina Ricci, for example, the archive pieces didn’t really resonate. The heritage of the perfume, L’Air du Temps, was perhaps more evocative. But from the minute I was interested in fashion, Lanvin was a house that I thought about. We even referenced Lanvin on a number of different occasions when I was at Louis Vuitton, though not in a literal way. I remember then looking at the Lanvin archives and thinking, “God, I’m so jealous of having all that to pull from.” And here I am.