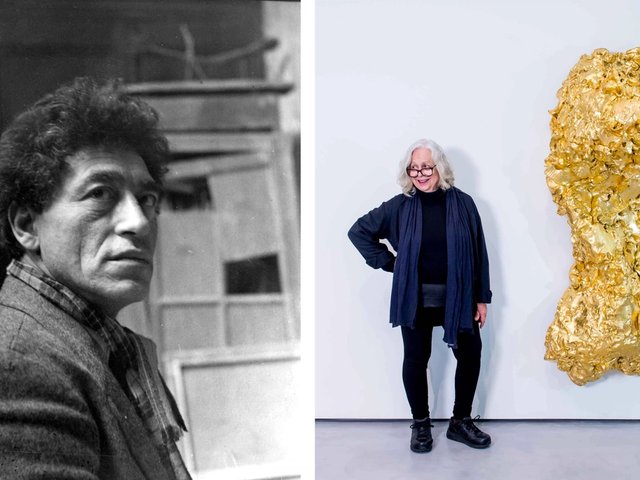

A revelation of the year so far in London has been the new space for art at the Barbican. A former restaurant there has been redesigned and has hosted two of 2025’s best shows, in which the contemporary artists Huma Bhabha and Mona Hatoum have been shown alongside Alberto Giacometti.

I have written before about how artistic languages separated by decades or centuries can have an alienating effect on each other if shown together without subtlety. But these shows are perfectly judged and paced. Of course, it’s partly about the right choice of artists: Bhabha’s and Hatoum’s work engages with Giacometti’s in form or subject, and sometimes both. But part of the joy of these shows—curated by the Barbican’s Shanay Jhaveri alongside Émilie Bouvard, the director of collections and scientific programme at the Fondation Giacometti—is in the way that affinities and distinctions are equally welcome.

The excellent exhibition guide for the Giacometti-Hatoum show notes that both artists are “preoccupied with the human body in its vulnerability and resilience” but points out that Hatoum never directly explores figuration, Giacometti’s ultimate obsession. In formal terms, Giacometti mostly built his sculptures up from nothing to something, while Hatoum often takes the found object and manipulates it.

But comparisons are not forced. The lightness of the associations is exemplified in the way that the form of Giacometti’s Figurine Between Two Houses (1950), a walking figure in a vitrine between two boxes, is gently echoed in the film of Hatoum’s performance Roadworks (1985), in which she walked barefoot, dragging her Dr Martens boots behind her by their laces: she is “contained” like Giacometti’s figure, but in a monitor showing the video.

Carrying emotional force

Most crucial is that Giacometti’s work is not ossified. He feels like a living artist. Bhabha and Hatoum have been presented almost as collaborators. In the Hatoum show, Giacometti’s sinister head with a vastly extended nose, Le Nez (1947), is contained within Hatoum’s cage, Cube (2006), formed from steel bars whose shapes relate to the metal grids covering medieval windows. It only emphasises the primal and visceral impact of Giacometti’s tortured visage. Elsewhere, his Woman with Her Throat Cut (1932)—one of his early sculptural compositions laden with Surrealist sex and violence—is in sight of Incommunicado (1993), Hatoum’s child’s cot whose springs have been replaced with cheese wire, turning it into a domestic killing machine.

Bhabha and Hatoum have been presented almost as Giacometti's collaborators

But while full of aesthetic and lyrical conversation and play, both exhibitions carry an emotional and political force. When he made them, Giacometti’s post-war sculptures seemed aptly to reflect the anxieties and fragility of humans in a world reeling from the horrors of the Holocaust. Both Bhabha and Hatoum have created images that speak to more recent global inhumanities. Hatoum has made numerous works reflecting on her experience as a woman born in Beirut to Palestinian parents.

I saw the Giacometti-Hatoum show the day after the International Association of Genocide Scholars passed a resolution stating that Israel’s conduct in Gaza meets the legal definition of genocide, as laid out in the UN convention. Time and again, images of Gaza today echo Hatoum’s work, from Remains of the Day (2016-18), a domestic space apparently decimated after a cataclysmic event, to Interior Landscape (2008), a bare bed with barbed wire springs and a pillow into which the historical map of Palestine has been embroidered in human hair.

Next to these works, Giacometti’s figures, with their “extraordinary but apparently perishable grace”, as Jean-Paul Sartre put it, seem as if made yesterday; eternal emblems for humanity amid a brutal world.

• Mona Hatoum, Encounters: Giacometti, the Barbican, London, until 11 January 2026