The most expensive of work of Islamic art ever sold was a carpet. At around nine feet long, it was made for the throne dais of the Shah of Iran in the early 17th century. At Sotheby’s in New York in 2013, it made almost $34m.

But the market has changed since then. Ten years later, Christie’s in London offered the Baron Edmond de Rothschild Imperial Safavid Carpet for £2m to £3m. Almost certainly woven for one of the Safavid kings, the 550-year-old textile retained a startling vibrancy; the leading artisans of the Islamic world had woven leaping birds and curling tendrils on 16 feet of rich red wool, dyed in pigments and carried thousands of miles across the Silk Road to the royal atelier in Qazvin, Northern Iran. And yet, it failed to make its reserve price, which was a worrying sign of shifting fortunes in the nexus of styles, schools and significances that dealers and auction houses call ‘Islamic’.

In recent years, aging collectors, maturing museums and shifting capital have transformed a market which has always lacked a fixed definition. That elasticity has now allowed the market to reposition itself: traditional mainstays—such as Persianate paintings from the wider world of Persian-speaking courts stretching from modern Iraq to India—have diminished in focus and market share, while paintings from India and religious artefacts from historic Arab polities are on the rise.

At Sotheby’s most recent sale in April, 27 Persian works were offered and 14 were not sold. This continued the long-standing slide in the price of art; in Sotheby’s slightly slimmer October 2024 sale, 22 Persian works were offered, comprising mainly manuscripts and early metalwork, of which nine failed to sell.

According to the London-based Islamic art dealer Mehmet Keskiner, this has a lot to do with geopolitics. Because of sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran, works “of Iranian origin” cannot legally be exported into the US or UAE, even if they are bought in Europe. “People like FedEx don’t want to ship Persian material,” he says. “So that definitely makes it less attractive to buyers.”

In addition, as former Sotheby’s deputy chairman for the Middle East, Roxane Zand, puts it, collecting tastes all too often follow national origin. “The current situation in Iran has meant that collectors of Iranian art are wary and sales of Persianate art are in a slump,” she tells The Art Newspaper. Iranians outside the country are consequently not buying, while those inside Iran who might wish to are unable to do so due to banking sanctions.

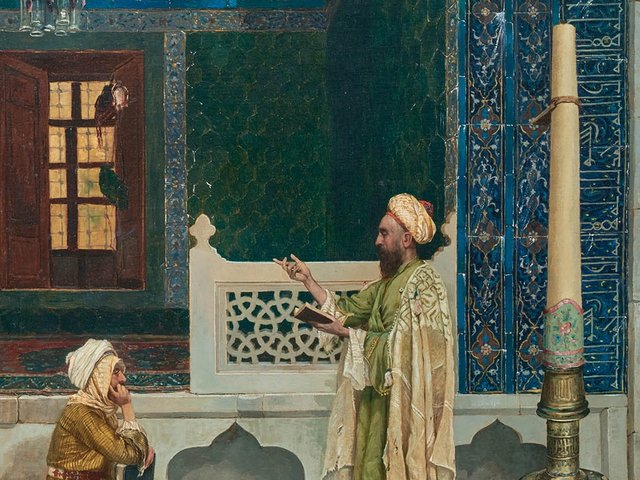

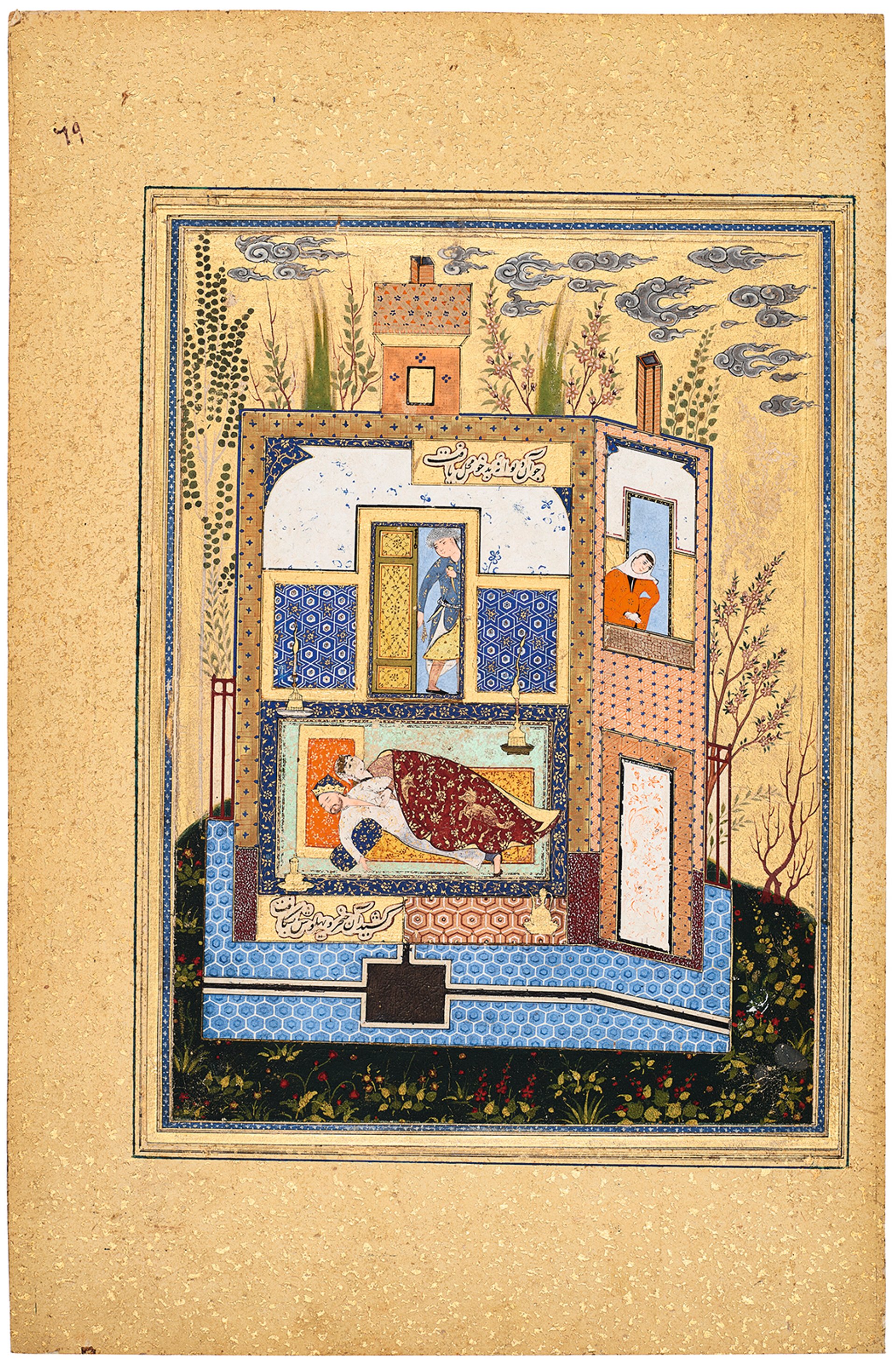

The Murder of Khusraw (around 1570), inspired by a work by the poet Hatifi, was sold at Christie’s in 2024 Christie’s Images LTD

The rise in Mughal art

This decline also seems to be the result of a generational shift, as the dealer Damian Hoare observes, away from “passionate and connoisseurial Iranian collectors… who had always previously been ready and willing to support their own material”. The younger generation, Keskiner says, are “more interested in contemporary than classical art”.

This has resulted in “an all-together thinner market”, Hoare says. Supply has dried up, both because people are unwilling to sell in an unpropitious market and since, as Keskiner puts it, museums have already “been buying for the last 30 or 40 years and have bought up all the good things”. This means that, in most cases, interesting works considered mid-range will only come up for sale when their owners pass away (as the vibrant Middle Eastern departments of Paris auction houses such as Millon would attest), while works at the very top of the market will appear more rarely. At the same time, Hoare adds, “blue-chip material such as miniature paintings from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp continue to perform very well”. One of those, a manuscript, sold for just over £8m in London in 2022, and several dozen more remain in private collections.

At the same time, there has been a steady rise in prices paid for Mughal art, reflecting the explosion of South Asian capital onto the international art market; Indian art has tended to carry the day in the recent sales of Islamic and Indian art, with the high-quality paintings of elite provenance performing best at auction. At Sotheby’s in April last year, an illustration from Prince Khurram’s Album that had belonged to the 17th-century Mughal ruler, better known as Shah Jahan, depicted his ancestor, the globe-trotting warrior-king Babur. It sold for over £530,000, almost 20 times its estimate. It is no surprise, then, that the highlights of Sotheby’s Islamic sale on 29 October were mostly Indian.

However, all is not lost for Islamic art. Saudi patronage has picked up dramatically in recent years, and it has tended to prioritise works with sacral significance of some sort. During this year’s Islamic Art Week, the arts non-profit Turquoise Mountain, founded by King Charles III, will display a series of works produced for Saudi Arabia’s King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture (Ithra) at Sotheby’s, including Afghan woodwork and Syrian marquetry. And as Islamic art increasingly gestures towards the contemporary, with new biennials in Jeddah and Bukhara beginning to shine a light on new approaches to the visual traditions of the Islamic world, this will likely soon be reflected in the market. It seems to herald “an increase in the practice of heritage-based art from the region”, Zand says. “At some point, Islamic art will no longer refer exclusively to antiquities.”